(Joe LeSueur)

This essay is an appreciation of Joe LeSueur’s memoir of his friendship with the poet Frank O’Hara and the apartments they shared from 1955 to 1965. Joe paints a fascinating portrait of Frank as a hard-drinking poet. In the 15 years he worked in New York, before his death at 40 in 1966, Frank made a major assault on the content of American poetry, with his wryly named New York School of Poets, which included John Ashbery, Kenneth Koch and James Schuyler. He became the center of a social scene of parties and gallery openings, mixing painters with poets, writers and dancers. Frank lionized his painter friends like Bill de Kooning, Grace Hartigan and Larry Rivers in his poems. Frank also promoted them first as a critic for ArtNews, and then as an influential associate curator at the Museum of Modern Art, where he handled foreign exhibits, raising the stature of Abstract Expressionism and American modern art.

Frank was a promiscuous lover, but his sexual ideal would be a close male friend, who was usually straight or mostly straight. He always had a female muse, from the playwright Bunny Lang during his Harvard years, to Jane Freilcher and Grace Hartigan. When the women got married, the friendship would fade. Frank finished life adoring the Hamptons socialite Patsy Southgate, at the time of his death in 1966.

Digressions is an affectionate but often very bitchy memoir of gay life and the New York art scene in the 1950’s and 1960’s.

I added material from Brad Gooch’s brilliant O’Hara biography City Poet, as well using interviews I conducted with the poets Edward Field and Brigid Murnaghan.

Digressions on Some Poems by Frank O’Hara by Joe LeSueur (2003)

Joe LeSueur was an angelic-looking blonde beauty and World War II veteran when he met the writer Paul Goodman in a gay bar in Los Angeles that was being raided. Goodman told Joe to look him up when he moved to New York.

The eldest son from a large working-class Mormon family, Joe knew that he had to get out of Los Angeles, away from his family as a young gay man. “I knew that I was different from my brothers and sisters,” wrote Joe LeSueur, in his memoir Digessions on Some Poems by Frank O’Hara, “and knew by the time I was an adolescent, that the day would come when I’d have to carve out a life of my own, a deviant, subversive life that would be intellectually stimulating.”

The memoir concentrates on Joe LeSueur’s 15-year friendship with the influential poet Frank O’Hara and the decade that they spent as roommates in four different apartments in Manhattan—two dirty tenements filled with roaches, one apartment without a shower, and finally, a loft on Broadway that could accommodate Frank’s large art collection of gifts from his artist friends, including Elaine de Kooning, Larry Rivers and Grace Hartigan. In the last apartment, their roommate relationship had frayed, and Joe moved out in the fall of 1965. During the following summer, Frank was mortally injured in a freak dune buggy accident on Fire Island.

Joe LeSueur’s book is about the friendship of two working-class gay men who came to New York (Frank was from the Boston area) and entered the vibrant art and literary scene in Greenwich Village. Rejected by the established poets, Frank O’Hara threw himself in with the artists at the Cedar Tavern, with the Abstract Expressionists known at the New York School, including such artists as Franz Kline, Bill de Kooning and Philip Guston. With three other poets—John Ashbury, Kenneth Koch and Jimmy Schuyler, Frank pioneered a new modern form of naturalistic, “I do this, I do that” kind of poetry that received the label the New York School of Poets, a nod to the painters they had become close with.

Meeting during the height of the sexual repression of 1950’s America, Joe and Frank were never in the closet. In an era when gay men and lesbians were arrested in bar raids by the NYPD and gays outed at work were often fired, both men had prolific, open sex lives. Early in the roommate relationship, they occasionally had sex with each other, but Joe preferred picking up strangers on the street or in bars and having sex. Frank tended to sleep with his friends, be they gay or straight, having a long-term affair with the painter Larry Rivers, between his relationships with women, as well as with the married landscape painter Fairfield Porter.

Joe LeSueur opens the memoir with the delightful essay “Four Apartments,” written in 1969. Joe and Frank met at a New Year’s Party in 1951, at the poet John Ashbery’s apartment. They became fast friends. At that time, Frank had gotten his first job at the Museum of Modern Art selling postcards and running the information desk.

In 1955, Joe moved into Frank’s apartment on 326 E. 49th Street, across from the United Nations. It was a dirty tenement apartment they nicknamed “Squalid Mansion.” Their social scene consisted of art openings, museums and long nights at the Cedar Tavern or the San Remo, a half-gay literary bar on MacDougal Street. At MoMA, Frank would write his poetry between work phonecalls.

Both men drank heavily. At night, Frank would often have make-out sessions with a black security officer working at the guard booth at the UN, not far from their 49th Street apartment. Once, drunk on the subway, Frank overshot his subway stop, and in an outerborough subway stop blew a token both clerk. Frank also had a sexual relationship with the black postman who delivered their packages. Frank and Joe referred to him as “Aunt Jemima.” (Joe insisted in the memoir that Frank had genuine interest in black men as sexual partners, despite such gross racist talk.)

Frank and Joe’s idyllic and filthy life at Squalid Mansion was interrupted when the poet Jimmy Schuyler, who had previously lived in the apartment, moved back in without notice and took one of the two bedrooms. The severely depressed Schuyler cast a pall over the apartment, slept for many hours and would shoot Joe murderous looks.

To escape Schuyler, the two men moved out to an apartment over a bar at 90 University Place, which had the plus of being four blocks from the Cedar Tavern, but had no shower. Frank included the apartment in his “Poem(1957).” “I live over a dyke bar and I am happy,” he wrote. In the poem, Frank gets locked out of the apartment with the young alcoholic poet Brigid Murnaghan. They wound up sleeping at the painter Joan Mitchell’s nearby apartment.

Joe explains the background of the poem. Murnaghan was already a hot mess, famed for her drinking and ability to curse a blue streak.

In 1959, Joe and Frank moved to another cheap apartment on East 9th Street, on the edge of Tompkins Square Park. It was a grim tenement space with more roaches and a rat as big as a cat. The park was filled with angry, disgruntled poor Eastern European immigrants. This period, according to Joe, was one of Frank O’Hara’s most productive writing periods.

Their final apartment was a clean, spacious loft at 791 Broadway, across from Grace Church. Their roommate relationship ended there in January 1959, but they remained friends.

According to Joe LeSueur, Frank O’Hara was generous to a fault. If he embraced you as a friend, there were no limits. Frank always had a woman friend he was in love with. The first in New York City was the painter Jane Freilicher, and he wrote numerous poems, lionizing her.

Freilicher lived in the building of Kenneth Koch, a poet and Frank’s Harvard friend. At a party, he met both Freilicher and Larry Rivers. Frank fell in love with both. He and Larry Rivers kissed behind some drapes. Freilicher became his muse.

Freilicher and Rivers dated in the early 1950’s. When she broke up with him, he slashed his wrists. Rivers panicked, then called Frank, who rushed over, took the bleeding Rivers to the hospital, then out to Long Island, where their affair began. O’Hara also blocked Freilicher from seeing Rivers, preventing a reconciliation. Hartigan mocked the seriousness of Rivers’ attempt, saying that he checked to see that the phone worked before he cut his wrists.

After “Four Apartments,” there is an autobiographical piece, then LeSueur wrote the “Digressions,” analyzing and explaining the history behind about 40 of Frank’s poems.

When Joe arrived in New York in 1949, he started a sexual relationship with Paul Goodman, the writer who was one of the founders of Gestalt Therapy. Goodman was an entry into the intellectual circles of Greenwich Village. Goodman introduced Joe to members of The Partisan Review, Anais Nin, and the founders of The Living Theatre Julian Beck and Judith Malina.

Goodman was a repulsive lover—matted hair, sloppy dress and an unattractive face. Goodman also had an insatiable sexual appetite, picking up sailors and coming on to every young man in his circle. “How often to do attractive women endure sex with unattractive men, without anyone thinking twice about it? To some extent, I was like those women,” wrote Joe. Joe was an intellectual climber, enthralled by Goodman’s cultural capital and the access Goodman allowed. Goodman also used Joe to babysit his young son. Goodman’s wife Sally was aware of his sleeping with men. Joe would let Goodman have sex with him occasionally over the next three years, until he met Frank O’Hara.

Joe was working a miserable clerical job and was saving money to go back to Los Angeles forever, when he had the good fortune to be picked up by a wealthy Reichian therapist at the San Remo, who kept him a lover. When the therapist dropped him, he paid for Joe to go into therapy to deal with wartime trauma. Joe had been a medic during the Italian campaign, where he was given the horrific job of moving rotting, dead American troops, killed after a failed attack. His fellow medics were robbing the American corpses. Joe was also awarded a bronze star for staying with a severely wounded American soldier while under heavy fire.

Living together, Joe and Frank had a social life that involved dozens of painters and writers, like Joan Mitchell and Grace Hartigan. He wrote mini-odes to his friends. In the poem, “In Memory of My Feelings,” which was dedicated to Hartigan, Joe used it as an opportunity to describe Frank and Grace’s platonic love affair. Hartigan was a fierce figure, giving up her seven-year-old son to her mother so that she could live the life of an impoverished artist in a battered loft on Essex Street. She was both aware and resigned to the harm she was causing her son.

In the early 1950’s, Hartigan ate oatmeal and damaged fruit-stand vegetables to survive and continue painting. She worked as an artists’ model at an art school until the instructors attacked her painting style while she was holding nude poses.

(Grace Hartigan in the 1950's)

Hartigan inspired some catty rage in Joe. He calls her hefty, and recoils when Hartigan says that she wishes Frank wouldn’t bring his younger boyfriend out with them.

One night, while leaving the Cedar with Frank and Joe, a wimpy painter with a tiny moustache tagged along. Hartigan turned around and clocked him, knocking him into the gutter. Frank went to help the battered painter and Joe asked her why she hit the man. “‘I can’t stand a man who doesn’t act like a man,’ she said furiously.” Later, condemning Hartigan’s act to Frank, Frank said, what are you talking about? He deserved it. His love for Grace knew no end.

In the early 1950’s, Frank’s platonic love was focused on. Freilicher, known for her own wit. She eventually married Joe Hazan, a businessman, which put a chilling effect on Frank’s love for her. Frank dedicated his new book Meditations in an Emergency to Freilicher. Years later, she quipped that when Frank dedicated a book to you, it was sign that he had ended your friendship. Freilicher was replaced in Frank’s affections by Hartigan.

(Grace Hartigan)

Freilicher’s wedding to Joe Hazan took place at Joan Mitchell’s studio on St. Mark’s Place in 1957. As a cruel joke, John Bernard Myers invited Tennessee Williams, who had had an affair with Hazan in the late 1940’s in Provincetown, Mass.

(Joan Mitchell, Helen Frankenthaler and Grace Hartigan,1957)

Frank was big into collaborating with his artist friends. More than a dozen painters, including Hartigan, Rivers and Freilicher painted Frank, often in the nude. He also collaborated on Hartigan with a series of paintings called “Oranges,” that integrated his poems into the painting.

Myers, the eccentric director of the Tibor de Nagy Gallery, pushed collaboration between artists and painters. He started the Artists’ Theatre. Frank had written the play “Try, Try, Try,” with the sets by Larry Rivers. Myers also published Frank’s first chapbook of poetry, A City Winter, in 1952. Myers was also the person who coined the term New York School of Poets, giving Frank and his fellow poets a distinctive brand.

(J.B. Myers)

Myers had had an affair with Rivers early in the 1950’s and pushed Rivers’ art at Tibor de Nagy, relentless promotion in exchange for sex. When he was spurned for Frank O’Hara, Myers would show up keening at Rivers’ door late at night. Though enraged at Rivers, Myers still promoted O’Hara, encouraging collaboration between the poet and other artists.

Joe LeSueur’s memoir chronicles a swirling social scene. Frank often went to the macho Cedar Tavern, hanging out with the lions of Abstract Expressionism, including Bill de Kooning, Franz Kline and Phillip Guston. Frank didn’t like the self-destructive Jackson Pollock, because he referred to Frank and Larry Rivers as “faggots” when he found out they were sleeping together.

Joe preferred the San Remo, a Mob-owned bar on MacDougal and Bleecker, run by tough Italians from the neighborhood, who would beat unruly patrons with a billy club kept behind the bar. Frank musing on the bar, noted in a poem, “The penalty in the Big Town is the Big Stick.”

The San Remo was more literary, with the British poet WH Auden and his boyfriend Chester Kallman holding court there. Kallman would regale friends with stories of picking up hustlers, giving loud, explicit details. According to the poet Edward Field, Kallman had the bad habit of picking up vice cops. Auden would have to bribe judges to get Kallman out of trouble. Auden eventually moved Kallman to Greece, far away from the NYPD.

Random pick ups could have their dangers. Joe recounted being pummeled by a handsome man who had flirted with him on the street. At a party, O’Hara had invited some rough trade, a tough often violent young man who exchanges sex for money, into a bedroom, and the man started beating him. When Frank cried out, his friends rescued him.

The Beat writers, including Allen Ginsberg, Gregory Corso and Jack Kerouac drank at the San Remo, as did Malina and Beck, the married founders of the avant-garde Living Theatre. Beck preferred men. The petite, intense Malina was a one-woman sexual revolution, picking up the writer James Agee and others at the bar. Sometimes, Malina would have multiple sexual encounters in one night around the Bleecker Street area.

Frank wrote euphorically gay poems, like “At the Old Place,” written in 1955, about Frank and Joe, and their literary friends John Ashbery and the painter John Button go a gay dance bar and have a euphoric night dancing, with Frank dancing the Lindy with his friends. The poem did not actually see publication until three years after Frank’s death in 1969.

In 1955, Edward Field was a young poet and World War II combat veteran when he met Frank at a reading at the Egan Gallery. Field was using group therapy in a desperate attempt to stop being gay. He and O’Hara dated and slept together for about four months.

For Field, Frank was a symbol of what a non-self-loathing gay man could be, which would help Field in his own last relationships with men. Frank pulled Field into his social circle. Field remarked that despite the grimness of the McCarthy era, Frank and his artist friends were decidedly nonpolitical.

The affair ended suddenly when a Penn Station locker that held several of Frank’s manuscripts and his typewriter was emptied. Frank went into a paranoid tailspin. Field believes that there may have been marijuana in the locker, for Frank was supplying his Hamptons friends with pot. Or that there were incriminating letters about drug use. Frank could have also been holding heroin for his sometime lover Larry Rivers, who was still a junkie at this point.

In 1956, Pollock was killed in a drunk driving accident in the Hamptons that severely injured his new mistress Ruth Kligman and killed a young woman friend of Kligman’s.

(Jackson Pollock and Ruth Kligman)

Pollock’s death and funeral inspired “A Step Away from Them,” his great memorial poem. Written on August 16, 1956, the day after Pollock’s funeral, Frank opens the poem by noting the construction workers in Times Square, putting sandwiches and cokes in their dirty bodies. Frank has a cheeseburger and a chocolate malted at Juliet’s Corner, then watches a rich woman, “a lady in foxes,” put her poodle in a cab. The kicker is the memorial lines: “First Bunny died, then John Latouche/Then Jackson Pollock. But is the/ earth as full as life was full of them?” Joe LeSueur sees “Step Away” as the first of Frank’s “I do this, I do that” poems.

After Kligman recovered from her injuries, an enthralled Bill de Kooning started dating the zaftig brunette. In an effort to give the new couple social legitimacy, against Joe’s wishes, Frank had invited them over for dinner. Somehow, Elaine de Kooning, Bill’s long estranged wife, got wind of the dinner and insisted she come over to see Frank for a drink. She stayed for Bill and Ruth, humiliating her husband’s new girlfriend.

(Ruth Kligman and Bill de Kooning)

The next night, Kligman and Bill went to the critic’s Harold Rosenberg’s apartment for a party. At the party, Rosenberg’s wife May loudly called Ruth “a slut” in front of other guests. Horrified, Kligman tried to make de Koomning leave, but he refused, going to get a drink. The infamous couple stayed until the end of the party. Ruth Kligman never achieved social legitimacy with the Cedar crowd. Bill de Kooning’s energies were also soon distracted when his other mistress Joan Ward gave birth to his daughter Lisa.

Frank was famous for his generosity towards his friends, as well as promoting his own group. As a critic for ArtNews, Frank repeatedly reviewed and promoted Larry Rivers’ exhibits, even though they were lovers. He also positively reviewed Hartigan and other friends, helping to raise their stature in the downtown community.

Despite the uncomfortable conflict of interest with Frank being a prominent art critic and later an influential curator, the four apartments Frank and Joe shared were crammed with artwork, gifts from Frank’s friends, including paintings by Grace Hartigan, Larry Rivers, Jane Freilicher and Elaine de Kooning, who once quipped that the apartment looked like a group show. A glorious loaner of a Bill de Kooning painting held a prominent space between two filthy windows in the East 49th Street apartment. “Well, I have my beautiful de Kooning to aspire to,” wrote Frank in his 1955 poem "Radio." “I think it has an orange/ bed in it, more than the ear can hold.”

Late at night, Frank’s generosity gave way to attacks on his friends due to the heavy drinking. In his own chaotic memoir, Larry Rivers wrote of Frank’s vicious character attacks coming out of his bow-shaped lips directed at those closest to him under the guise of constructive criticism. The nastiness would usually be glossed over in a phonecall the next morning.

Despite his ethereal good looks, in the mid-1950’s Joe intentionally cultivated a campy nasty style, making cutting, sarcastic comments about the people in his circle. He recounted meeting the artist Bob Rauschenberg, known for his warm, gregarious personality. He focused in and found he hated Rauschenberg’s maniacal laugh. P48. He proudly recounts in the memoir, that the pianist Gold commented that “I looked like an angel until I opened my mouth and shit came out.” P48. He boasted to the novelist James McCourt that his nickname was “Joe Sewer,” for all the filth that he spewed.

Through the fifties, Joe worked a dead-end job at a bookstore, and pursuing copious mount of anonymous sex and pick ups on the street. On day, Frank coaxed Joe to work on a play, which led to writing teleplays. Joe wound up writing for such soap operas as “Guiding Light,” “Ryan’s Hope” and “Texas” through the 1970’s and ‘80’s.

Brigid Murnaghan, the poet Joe knew in the late 1950’s, was famous for her sailor’s mouth. I interviewed her in 2008, at her apartment on Bleecker Street, where she had lived for 50 years. She had her own take on Joe LeSueur. When asked if she knew Joe, Murnaghan mused, “They [Joe and Frank] must have fucked once or twice. They weren’t a couple. They were friends.” On Joe’s abrasive personality, she said, “He was a cunt. It fits right on the money. That kind of looks, I knew he wouldn’t age gracefully.”

In his memoir, Joe was able to reveal lost items of New York gay culture. When he was first arrived in New York in 1949, he was a kept boy, meeting his lover at a dreary apartment building on at 333 W. 86th Street, where multiple apartments were rented for gay trysts.

Years later in 1959, Joe and Frank are invited to a literary stag party at the same building, including Tennessee Williams, the gallery owner John Bernard Myers, and the uber-macho closeted Japanese writer Yukio Mishima. The apartment was a sprawling two bedroom, rented by Tennessee. There are several hustlers to pleasure the guests. Truman Capote was supposed to show up, but never did. Tennessee appears in an embroidered robe, smoking a foreign cigarette, with a hustler in tow.

Joe only remembers fragments of the evening, but describes a dialogue with Mishima. Was Mishima attracted to Caucasian men? Very much so, said the hyper-macho, closeted writer. Their cocks are bigger. Wasn’t this just a stereotype? asked Joe. “Come to Japan, see for yourself,” said the size queen.

(Yukio Mishima, size queen)

For Joe LeSueur, Digressions is about capturing the heady days of the bars and lofts of the 1950’s art scene and following the life of Frank O’Hara. Joe noted Frank’s daily routine in the last few years of his life. He would wake after three or four hours of sleep. He’d smoke and to stave off the daily hangover, he’d drink orange juice laced with bourbon while reading a little Gertrude Stein, then making phonecalls. He’d get by work by 10, work with great efficiency for several hours, then would take a two-hour lunch with friends, often drinking one or more martinis. He might write a poem. In the evening, Frank would meet friends for an art opening, the ballet or a party, continuing the drinking.

In 1959, Hartigan suddenly married a gallery owner on Long Island and moved out there. The marriage was short lived and they divorced within the year. Hartigan was also in therapy, and her therapist convinced her that her platonic love affairs with two gay men, Frank O’Hara and her gallery owner John Bernard Myers, was preventing her from finding a sustainable marriage. She ended her friendship with Frank by letter.

Soon after, Hartigan fell in love with and married a famed research scientist and moved to Baltimore. Hartigan was at the height of her career. The statuesque blonde was the most famous female second-generation Abstract Expressionist. As the New York Times wrote years later, when she left New York, her art career wound up sinking as quick as the Titanic. Hartigan had a rocky road in Baltimore. She drank heavily and tried to commit suicide. She eventually joined the faculty of the Maryland Institute College of Art. With Hartigan in mind, the college created a graduate program, the Hoffberger School of Painting, which she ran from 1965 until 2007. Hartigan died at 86 in 2008.

One of the most breathtaking poems Frank wrote was “The Day Lady Died,” in 1959. By the late 1950’s, as the Cedar Tavern became packed with tourists, many of the painters and other regulars started going to the Five Spot, at 5 Cooper Square, on the bowery. The Temini brothers had taken over their father’s working-class bar, bought an upright piano and got a cabaret license in 1956. Jazz bands started to play there.

(The Five Spot, 1950's)

One night, O’Hara was in the bar when a battered middle-aged woman stood up from her table and started to sing. It was the great Billie Holiday, the blues singer, who had had her cabaret license revoked for multiple convictions for heroin possession. She was not allowed to sing in clubs in New York. Her weathered, shattered voice mesmerized the bar.

(Billie Holiday)

Two years later, when he found out that Holiday had died, chained to an infirmary bed with a NYPD officer standing guard, Frank wrote a pedestrian beginning to this poem, He is getting his shoes shined, waiting for the train to the Hamptons, where he will be dining off others. He picks up a bottle of strega for his hosts and two cartons of cigarettes, then gets the Post, and sees Holiday’s face on the front page. Franks wrote, “…and I am sweating a lot now and thinking of/leaning on the john door in the 5 Spot/ while she whispered a song along the keyboard/ to Mal Waldron and everyone and I stopped breathing.”

Over his decade at MoMA, Frank had gone from running the information desk to becoming an associate curator, putting together international exhibits on modern American painting, promoting the painters and friends he adored like Bill de Kooning, Franz Kline and Grace Hartigan.

Standard Oil heir Nelson Rockefeller and other American Cold Warriors were on the board of MoMA in the 1950’s and ‘60’s. They had a keen interest in financing exhibits that spread the gospel of American modern art, particularly the Abstract Expressionists. The international exhibits were financed, in part, by the Central Intelligence Agency.

(Frank O'Hara at MoMA)

As his MoMA responsibilities mounted, O’Hara’s poetry was pushed to the side. In 1965, he only wrote two poems. In 1966, the year of his death, he only wrote one.

Frank found his new muse in Patsy Southgate, the gorgeous and slender blonde socialite, who lived out in Southhampton. Southgate had her own interesting history. She lived in Paris in the early 1950’s and was married to Paris Review founder and novelist Peter Mattheissen. In an era of zaftig actresses and models, Southgate stood out for her waif-like beauty. She was supposed to be the inspiration for Jean Seberg’s American girl love interest in Jean-Luc Goddard’s “Breathless.”

Southgate was dating the bad-boy painter Mike Goldberg, who was famous for his crude sexual appeal and was one of Frank’s straight-boy crushes. Goldberg had had a tormented sexual affair with the painter Joan Mitchell for several years in the early 1950’s and had spent time in a psychiatric hospital after he forged $500 worth of checks that he had stolen from Mitchell’s ex-husband Barney Rossett, the owner of Grove Press. Goldberg was viewed by some as a con man and sociopath. Through Frank’s reviews and promotion, Goldberg became a somewhat successful painter.

Southgate had two young children from her first marriage. She was on the cusp of marrying Goldberg, who was close to both Frank and Joe. In a touching scene in Digressions, Southgate speaks with Joe and Frank, telling them that marrying Goldberg was the same as marrying the two roommates, who were close to her kids.

The marriage went ahead and lasted about five years. One night, a drunk Bill de Kooning came to Southgate’s house. He told Goldberg that he could go to his house and pick out two de Kooning drawings for himself. Up to his old tricks, Goldberg went to the house and took 10 drawings, forging de Kooning’s signature on some and selling them.

De Kooning wanted to press charges. Through hard work, Southgate was able to convince de Kooning that Goldberg should be sent to a psychiatric hospital instead of prison. While Goldberg was committed, Southgate was able to divorce him. “Mike has a psychopathic personality,” said Southgate after the divorce.

(Mike Goldberg and Frank O'Hara)

According to the O’Hara biographer Brad Gooch, in the last year of his life, Frank’s beloved Abstract Expressionism were being overtaken Pop Art, as signified by Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein. Frank was on the cusp of making the transition to accepting Pop Art when he was killed.

Digressions is also about Joe LeSueur settling scores. His mentor and ex-lover Paul Goodman gets worked over. By becoming friends with Frank, Joe broke Goodman’s predatory hold on him. Frank and Goodman couldn’t stand each, and Goodman would routinely attack Frank. In the book, Joe extols the virtues of the avant-garde Living Theatre, except when they produced Goodman’s plays. His play “Faustina” is so wretched that an actress onstage can’t bring herself to recite Goodman’s lines.

Goodman was a prolific writer and pacifist, living in poverty for decades and off the wages of his common-law wife Sally. He wrote plays, turgid novels and essays. He was also one of the founders of Gestalt therapy and was famous for sleeping with his patients and in the case of Judith Malina, with her boyfriends.

In the early 1960’s, Goodman published the book, Growing Up Absurd, which chronicled the post-World War II youth culture. He became an icon of the anti-war movement. Joe noted this success, but took some delight that Goodman fell back into obscurity after he died in 1972.

In the late 1950’s, Frank memtored LeRoi Jones, a very dapper, ambitious Black poet from Newark, who’d been kicked out of the Air Force for reading the Partisan Review. The handsome Jones eventually pubished Yugen, a poetry magazine and the Totem Press with his wife Hettie Jones. Yugen published Frank and other New York School poets, Beat poets like Allen Ginsberg and the Black Mountain poets.

In “Personal Poem, 1959,” Frank writes of having lunch with Jones and his great affection for the poet. In 1963, after the assassination of Malcolm X and the riots in Newark, became more radicalized and was drawn to Black militant politics. He left his wife Hettie and children in the bohemian Village and moved to Harlem and became involved in the Black Arts Movement. He changed his name to Amiri Baraka and eventually married a Black woman. He also savaged his two old friends, Frank O’Hara and Joe LeSueur.

(LeRoi Jones and Frank O'Hara)

Joe detailed in Digressions that the famously unfaithful and heterosexual LeRoi Jones spent many nights in Frank O’Hara’s bed, first in the University Place apartment, then the tenement on East 9th Street. When asked by Leonard Bernstein about Jones/Baraka’s betrayal, Frank said, “… that LeRoi was someone I loved and I couldn’t possibly discuss anything like that with him”[Bernstein].”

When asked by friends why he accepted Frank and Joe’s hospitality for all those years, Baraka said, “I was pissing in their beer.”

Academics do discuss LeRoi and Frank’s friendship as having elements of an intense flirtation. Gooch’s City Poet mentions nothing of Joe’s version of the alleged sexual affair, but the Gooch book came out before the revelations in Digressions. Gooch does recount O’Hara telling people he believed LeRoi was gay.

Towards the end of their roommate relationship in the mid-1960’s, Frank openly poached Joe’s lovers, including Joe Brainard, an artist famous for his speed-inspired drawings and collages. There was also J.J. Mitchell, the son of an admiral and a sexy young man on the scene. Joe dated him first then Frank took him. Joe recounted with rage the time J.J. walked stark naked out of Frank’s bedroom for the morning coffee.

(O'Hara, Joe Brainard, poet Frank Lima, LeSueur)

J.J. was with Frank on Fire Island the night Frank was mortally wounded after being hit by a dune buggy on a dark beach. Frank was in dune buggy taxi that had stopped for mechanical problems. He stepped out from behind his stalled taxi and was hit by another dune buggy carrying a young couple out on a date.

Frank had extensive internal injuries and was taken to a small hospital on the mainland, with substandard trauma facilities. His powerful friends rallied around him. Bill de Kooning showed up to the hospital with a massive checkbook, offering to pay for all medical expenses. After Frank’s death, a doctor grimly noted that it was likely that Frank would have survived if his liver was not so severely damaged from 20 years of heavy drinking.

In their affair, J.J. Mitchell and Frank had bonded over their heavy drinking. Three decades after Frank was killed, Joe goes out of his way to portray J.J as a sad barfly. Towards the end of the book, he publishes a poem by Thom Gunn called “BAR on Second Avenue,” which portrays the once-beautiful J.J. chatting his head off and boasting, “Why don’t you know, his smile triumphant, I was Frank O’Hara’s last lover.” Gunn edges away after a half hour, comparing J.J. to Nell Gwyn, a beautiful 17th century actress, more famous for being the mistress of the English monarch Charles II.

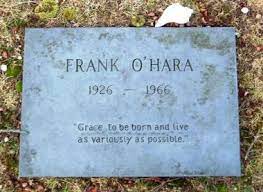

Frank lingered for two days with his grievous internal injuries. When he died, at the hospital his two siblings fought over where Frank should be buried. The brother, who had stayed in their claustrophobic Massachusetts town, wanted Frank buried in the family plot in Garland, the town Frank loathed. His sister Maureen, who had fled Garland at Frank’s urging years before, wanted him buried in the cemetery at Springs, Long Island, where Jackson Pollock was also buried.

A small impromptu wake sprung up at Joe LeSueur’s tiny Manhattan apartment, where grieving artists, curators and gallery owners gathered to mourn Frank O’Hara. The poet John Ashbery showed up with two large suitcases. For the poetry, he explained, and took Joe’s extra key to Frank’s loft. Larry Rivers and Ashbery made an unauthorized raid on the apartment, rescuing Frank’s scattered and chaotic archive of finished poetry and drafts. Rivers also retrieved several paintings he had gifted to the dead poet.

Frank O’Hara got his wish and was buried in Springs. The cemetery was packed with a who’s who of the New York art and literary worlds. His old lover and friend Rivers gave the main eulogy.

“Frank O’Hara was my best friend,” said Larry Rivers. “There are at least 60 people in New York, who thought Frank was their best friend.”

After Frank’s death, Joe LeSueur moved into Patsy Southgate’s East Hampton home. The two lived together, until Joe’s death in May 2001, at the age of 76.