(Jonathan Ned Katz)

Born in 1938, Jonathan Ned Katz was raised in the same Greenwich Village townhouse where he lives now. Educated at Antioch College, City College of New York, the New School and Hunter College, Katz broke onto the New York cultural scene in 1973 with his play “Coming Out!” which dealt with gay men and lesbians in the age of Gay Liberation in the early 1970’s. The play led to Katz being given a book contract to research and compile Gay American History: Lesbians and Gay Men in the U.S.A.

The 1976 publication of Gay American History began a radical confrontation with American academia, showing that America’s gay and lesbian history, though ignored or rejected, has existed since colonial times. Katz documented men being executed for sodomy in colonial Massachusetts, love letters that chronicled the romance of Alexander Hamilton with John Laurens during the Revolutionary War, women who passed as men in 19thcentury America and the forced commitment to psychiatric facilities of gays and lesbians. Katz also lays out the early battles for Gay Liberation, including Harry Hay’s founding of the Mattachine Society in the 1950’s. The book helped inspire the creation of gay and lesbian historical studies at colleges and universities around the country.

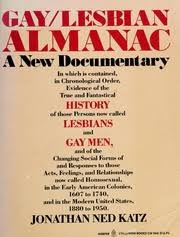

Katz’s other books include the Gay/Lesbian Almanac: A New Documentary(1983); The Invention of Heterosexuality(1995, with an introduction by Gore Vidal), and Love Stories: Sex Between Men Before Homosexuality(2001). He also has a memoir, Coming of Age in Greenwich Village: A Memoir with Paintings (2013).

Katz is also a fine artist, having worked in textiles and now painting.

In 2008, with initial support from Center for Lesbian and Gay Studies at the CUNY Graduate Center, Katz launched OutHistory.Org, a website which publishes original documents and scholarly articles on gay and lesbian history.

Dylan Foley interviewed Jonathan Ned Katz by telephone at his home in Greenwich Village on April 30, 2020. We discussed Katz’s childhood in the Village during the anti-communist Red Scare, his own sexual and political awakening when he joined the Gay Activists Alliance in 1971, and writing the play “Coming Out!”, where he came out to his mother in an ad in the Village Voice. We also talked about how Gay American History not onlychanged the discipline of gay and lesbian history, but also changed Katz’s own professional life, allowing him to teach at Yale and New York University.

Here is our interview:

DYLAN FOLEY: You were raised in the Village. Your father was an active Communist. What was his story?

JONATHAN NED KATZ: About the Red Scare, the first thing was that my father was a Communist in the 1930’s and 1940’s. I got a sense from him that it was out of concern during the Depression. He went to see this play, “One Third of the Nation,” it was about one third of the nation being poor, not having proper housing or food. It was a play from the ‘30’s.

Mainly what his Communism meant was a concern about social equality. That took the form of being very bothered by discrimination against black people. This was very early for a white guy. I asked him about the origin for this once and it was that there was one black boy who was very smart in his high school class in Bensonhurst, Brooklyn. The black kid was yelled at and called “Nigger” and all these things. My father felt for him. That was the origin of his caring about the discrimination against blacks.

This led to my father collecting jazz records and becoming an expert on the history of jazz. He was an expert on this major aspect of American culture that people didn’t even recognize then. He would play these records. I grew up with Bessie Smith being my lullabies.

We moved into this house in 1940, when I was 2. We rented an apartment. It was an odd place to live. There were factories, a frankfurter factory on one corner and a bakery on the other. There was a commercial building that is now condominiums and rare apartments on the other corner.

Sometimes walking by, the bakery workers would say, “Do you want an éclair?” I remember that as a kid.

I’d also see the rats going into the frankfurter factory to be ground into rat frankfurters.

My father produced two or three concerts at Town Hall. One was about Bessie Smith, after she died. It was a jazz concert. He got all these old jazz musicians. It was a big success.

My brother also became an historian of black history, from my father’s interest. I became an historian, finally, with one of the great influences being my father.

My father’s Communism, what it meant in the U.S., was that he was a Stalinist. He thought the negative things being said about Stalin were lies. Finally, he gave that up. He just withdrew from being a Stalinist.

(Love Stories: Sex Between Men Before Homosexuality, 2001)

DF: What was your father’s profession?

JK: That’s quite funny. My father was in the advertising business. They had Communists in the ad business. He took his job very seriously as the provider. In that age, the husband was the provider. My mother went back to work when I was eight or 10. She was an editor at Parents Magazine for years, telling people how to bring up their children.

DF: Was she a therapist?

JK: No, she thought she was.

DF: Was she a Freudian?

JK: [laughs] I’ve written about this in my memoir.

DF: Do you remember the Red Scare in Greenwich Village in 1949 or 1950?

JK: Yes, I do. My mother said to me, “You are not supposed to tell people in your class at the Little Red Schoolhouse in the Village,” a very progressive school, “that your father was a Communist.” Some of the other kids’ parents were Trotskyites.

I knew my father tried to get a gay friend of his into the Communist Party. My father was very bothered that the Party rejected the guy as a security risk. That was the same reason that the State Department was using to fire homosexuals and Reds, people who were called Reds, maybe who had gone to one meeting and had put your name on a petition for something and got on a list.

I must have said, “What’s a Communist? or “what’s a homosexual?” He must have said, “A man who loves men.”

It was interesting that my father had a friend who was openly gay, who felt this conflict with the Party and not letting the guy in.

My father would also point out homosexuals sitting in Washington Square Park. There was a place in the west side of Washington Square Park where all these men would sit. It was like a cruising place. It was quite public and quite obvious. My father said, “These are homosexuals.” That was part of my life in the Village.

DF: How did your parents deal with the Red Scare?

JK: My parents handled it pretty well. I wasn’t terrified of the FBI. I was warned that we might be visited by the FBI. One day, the bell rang and these two guys in the typical uniforms that they wore, these overcoats and pressed suits. J. Edgar Hoover made sure you had to dress in a certain way.

They wanted to speak to my father. I guess I got him. Maybe it was 1950. It was scary.

My father, after speaking to them in the front room I am sitting in right now, where I wrote this thing I am telling you about, where my father was interviewed by the FBI.

After they left, he told me that they asked if he was a card-carrying member of the Communist Party. “I said no,” he said. “We didn’t have cards.” It was like a joke.

DF: Did your father lose his job or get blacklisted?

JK: I think he did lose a job over it. Nobody looked into this at the time, but I suspect something happened with a major job he was supposed to get. He was supposed to go to a new art directing job that had been announced in the Times, but never happened. I suspect it was because the FBI called the Gravenson Agency, the new job. I think they also called the ad agency that he did work for, and they were okay with it. He stayed for a while with the old agency.

After all of this, he had a major heart attack. I think it was related to the anxiety. For 20 years, he survived. It was an important heart attack. He retired soon afterwards. He died in 1970. He was 70.

My mother was not a Communist at all. She was somewhat liberal. She was the Freudian. I had the Freudian versus the Marxist in my family. That’s why I was interested in both.

My father loved the sexual stuff in the blues songs. In black culture, there was a different attitude towards sex that was much freer than the uptight mainstream white culture of the time. We are talking about the ‘40’s and ‘50’s. In the ‘20’s, the raunchy blues lyrics started.

They were a very liberated family. My family walked around naked, but I grew up very repressed, a product of the 1950’s.

DF: You finally became involved in the gay liberation movement when you went to a Gay Activists Alliance meeting in 1971, at the age of 33.

JK: It was the winter of ’71 when I got involved with the GAA. I came to this church on 29thStreet. It was open to groups that were organizing.

Sometimes there is this door you walk through. There is this physical door, it wasn’t a metaphysical door. When you walk through, it is going to change your life and you don’t know how. On one side, there were three guys in what I guess you’d call anti-drag. They looked like Auntie Tilly dressed for church with hats. Oh my god, I guess we are all in this together. I was uptightand I was in the process of getting over all this repression. On the other side were these street transvestites action revolutionaries.

Then there were various things said at the meeting. One of the leaders, Arnie Kantrowitz, said we are fighting for our lives. It sounds banal, but it made me realize, “We really are fighting for our lives.” It’s my life that’s at stake there. I started going to demonstrations and going public. In a year, it led to me doing a play called “Coming Out!” The morning the play was to open, I got a phone call. It was my mother. She said, and I’ve told this many times, [Jonathan mimics a high-pitched, very prim voice] “Jonathan, is that you in the Village Voice?” Yes. There was an ad for the play. “Are you a homo-SEXUAL?” I don’t know why they say it with a hyphen in the middle. Yes. “Why didn’t you tell me?” “Because I knew that you’d act this way.”

It was the beginning of a new relationship with my mother. It took her about three years, but she ended up helping me edit Gay American History. I wanted her to edit it because it was better to have my critical mother, who was an editor, go over it before it was published. It was the beginning of a new life.

(Gay/Lesbian Almanac: A New Documentary, 1983)

DF: In your twenties, you didn’t address your homosexuality?

JK: I think there was a gay party that I went to. You just didn’t talk about being gay. You went to a party once in a while. I was so uptight about being gay and going to therapists to be straight. I did all that. Luckily, I got to a therapist who didn’t think that was my problem. I had other things. It was luck or maybe I chose her.

DF: You went to several colleges, including Antioch and the New School. Did you wind up with a masters?

JK: No. I didn’t finish with a bachelors. I was a dropout. It was the 1960’s. I didn’t do drugs. I didn’t even do rock and roll. I didn’t fit in any place. I didn’t fit in the gay scene because I was reading Marx. I had a deep interest in Marxism and sociology. I didn’t fit into the gay aesthetic scene. I didn’t fit in the left because I was gay. The leftist kids I knew seemed uptight. That may have been part of me being uptight. Some of them seemed to think there was going to be a revolution. That’s ridiculous. How could you think there was going to be a revolution?

Early on, I went on anti-war marches, before it became a mass movement.

DF: Please tell me about your play “Coming Out!”

JK: The play had bits that were dramatic, that could be acted out, scenes that were particularly dramatic. I think I had one piece that was from the colonial period.

One of the reasons why this play got so much attention was that it was the first introduction to people that there was such a thing as gay history.

The play was quite various. It had these dramatic speeches, political speeches at the end. We got away with the rabble-rousing speeches because the actors believed in it so much. It was so exciting. Because they were amateurs, there was a power to their acting.

The director of the play was a professional publicity agent for the theater, so he could call up the New York Times and say, “You should do a feature on this.” He got Marty Duberman to write a feature comparing my play to [Village playwright and Judson Poets’ Theatre founder] Al Carmines’ play. Duberman thought Carmines’ play [“The Faggot”] had traditional stereotypes about gay people.

Twenty years later, a director asked Al Carmines to play Walt Whitman in a play I did on Walt Whitman. He did it. We never talked about our initial contact.

DF: How did you get a book contract for Gay American History?

JK: My brother, an historian, had published a book with the editor that he had sent me to.

(Gay American History, the 1978 paperback)

DF: Where did you go for material?

JK: I was obsessive, I always say. Wherever I went, I talked about the research. At a gay party, somebody said, “Oh, you should look at Alexander Hamilton’s love letters to John Laurens, during the American Revolution.” I didn’t really believe it, but I read the letters and I think that Hamilton really was in love with this man. It turns out there was a sexual joke about the size of his nose. It was cut out of the letters, but you could figure it out what it was. Nobody’s talked about it. It is on OutHistory.org.

I went to the library and looked up Alexander Hamilton and there were these love letters. That was one example.

I heard there was a lot of stuff about homosexuality in the old medical journals. In some tower at Columbia, there were some medical journals I was trying to get a hold of. I had to bow down to some crazy guy. “Why are you looking at this, why are you here, what are your credentials?” I never had credentials. I got into the NYU libraries because the gay librarians got me a card.

When I went to the 42nd Street library, I had this experience. I told one librarian, that I was doing work on the history of homosexuality, which is what I would have said then. Suddenly, I was surrounded by a group of helpful librarians. All these queer librarians wanted to help me. It was following one clue after another. It turned out not to be that hard to find, once you start looking for it. It was just that nobody had looked for this material before.

What I did, the way I found stuff, was that I took every existing bibliography of homosexuality I could find, some of which were not medical, but the medical ones were helpful, too. I Xeoroxed them, I cut them up and put each entry on a 3 x 5 card and put them in chronological order.

The early bibliographies that were done by gay people were really useful. They helped me a lot.

(Jonathan Ned Katz and his file cards, 1970's. Photo by Fred McDarrah)

I ended up with thousands of file cards, they were in my office. It was quite a sight. Fred McDarrah from the Village Voice took pictures of me with the cards.

DF: Did Gay American History have a tremendous impact on your life?

JK: Yes. I was sent around the country on a train by my publisher because I don’t like to fly. I stopped in Chicago and was interviewed by Studs Terkel on his radio show. He got me to read the beginning ofGay American History, which is this very dramatic thing, sort of like the speeches at the end of my play. It’s quite poetic and I am very proud of the writing.

Studs Terkel documented the working-class history that had been ignored for so long.

DF: You’ve referred to yourself as a community historian and as a detective historian, for the work that you’ve down tracking down the hidden documents of gay history. In your academic travels, you’ve wound up teaching at Yale and NYU.

JK: I like that I made it to Yale, for a turn to be allowed in the walls of the Ivys. It was temporary. They only allow you in briefly, then they eject you.

DF: Were there parts of Gay American Historythat blew you away?

JK: Yes, a lot of it did. The discovery of passing women, which are called transgender now, which we understand in a different way. That was amazing, some of these discoveries, reading in a medical journal about a woman, who changed and lived as a man, had a hysterectomy, had two wives and ended up as a doctor and a novelist. It was an amazing story.

Contacting Harry Hay and talking with him was great. I first read about the formation of the Mattachine Society in 1950, when I was reading about it on the train going to my publisher to do some Xeroxing. They let me do Xeroxing there because I was concerned about the expense. I was reading about the Mattachine and realized that some of the people were still alive.

In this very room I am in now, Harry Hay once slept here with his boyfriend when he was in New York, to be the grand marshal of the Gay Pride Parade one year.

It was very exciting. In the aisles of the NYU Library, I was reading Hamilton’s letters, and I am like, “OH, MY GOD! They are love letters!” What to make of this? He’s famous for being a womanizer. None of that was mentioned in the play [The musical “Hamilton.”]. The most popular piece on OutHistory.org is about Alexander Hamilton.

(Gore Vidal)

DF: Gore Vidal wrote the introduction to your book The Invention of Heterosexuality. What were your impressions of him?

JK: I was very excited when I met Gore Vidal. He entertained me. I got a call from him. Did I want to pick up the introduction he wrote for the heterosexuality book? I went to the apartment at the Plaza Hotel and for about two hours, he entertained me. He gave me a monologue. Everything was “funny.”

Vidal was leaving for a party with Robert Silvers, the founder of the New York Review of Books. On the steps of the Plaza, we were waiting for a taxi. I always loved his work, especially the political stuff.

I said, “You sound like a Marxist.” “No, it is just living and growing up in Washington and seeing what the realities were.”

(The Invention of Heterosexuality)

DF: How has your historical process evolved from Gay American History to OutHistory.Org?

JK: First, it was just showing that there is such a thing as gay history through the documents, presenting the documents. It was appropriate to do that.

In 1983, with the Gay and Lesbian Almanac, I was a part of a group of people that was questioning this—how are these ideas constructed, how is the language constructed, how human relations are constructed. In different ways and very different ways at different times. The death penalty…you are executed if you are caught committing sodomy in the colonial times. In some other time, they gave you five years. It’s a big difference.

And all the different ways of conceptualizing what’s going on in these human relationships. It was fascinating and great to be involved with other people who were interested in this. We had study groups that met for years. It was fun to talk about this. We laughed a lot. A lot of the people were really smart.

I got much more interested in collecting this information, which still needs to be collected. There is still not enough knowledge about all of this, but I was really interested in how to analyze this material, how to interpret this, all the stuff that’s going on. What do the changes mean and what brought on these changes? Why do people think this way in this time and that way in another time?

I got more theoretical in a way, how you think about the material, rather than just getting [the documents]. There’s a put down of people. “Oh, you just do the manual labor of collecting documents…Oh, I do theory.” There is a horrible snobbery among gay scholars. “Oh, I do theory. I wouldn’t touch a document.”

DF: Do you have any new projects?

JK: I have a book protect, a contract that is almost signed. It is about Eve Adams, a Polish Jewish lesbian who immigrated to the United States and fell in with Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman, and gets on the FBI’s list and gets surveilled. She then publishes a book called Lesbian Lovein 1925, and they use that against her, to frame her. They put her in jail and deported her. During the war, she was in Occupied France and avoided the Nazis for three years, but in 1943, they finally caught up with her. She became a Holocaust victim, ultimately. Her life is very interesting.

No comments:

Post a Comment