Rosetta Reitz (compliments of Rebecca Reitz)

Rosetta Reitz was an avant-garde bookstore owner in Greenwich

Village in the 1940’s. She was also a jazz and blues audiophoile, who

used her love of music and history in founding Rosetta Records at

the age of 56, producing 19 albums in more than a decade.

Her records focused on the African-American blueswomen and singers

who were pushed to the side in the history of jazz and blues. Rosetta

produced meticulous albums with great liner notes full of the history

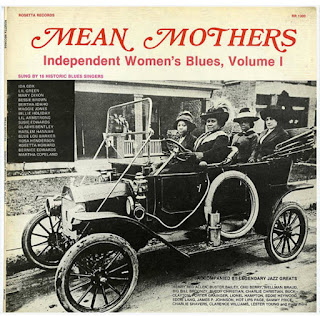

(Mean Mothers, compliments of Rebecca Reitz)

The catalog of Rosetta Records is a blues fanatic’s dream. Rosetta’s

first album “Mean Mothers” features Billie Holiday, Lil Green and

Gladys Bentley. The novelist Alice Walker has said she wrote her

breakout novel “The Color Purple” listening to “Mean Mothers.”

Other albums included “Super Sisters,” which features Ida Cox,

Sweet Peas Spivey and Ella Fitzgerald, and an album of the singer

(Ethel Waters, compliments of Rebecca Reitz)

I had interviewed Rosetta Reitz in 2005 for my “Last Bohemians”

photo exhibit, concentrating on the Four Seasons Bookshop, where

Saul Bellow, Ralph Ellison and Anais Nin were customers. We had

discussed a second interview, but Rosetta died of cardiopulmonary issues in 2008, before we could sit down again.

Recently, I reached out to Rosetta’s daughter Rebecca Reitz, who

gave me an extensive interview on her mother’s work as a pioneering

bookstore owner and champion of American blueswomen.

Rebecca also has a great website celebrating her mother’s work with

In addition to the albums, Rosetta produced concerts at Avery Fisher

Hall, Carnegie Hall and the Hollywood Bowl that allowed surviving

blues singers like Big Mama Thornton to perform in front of

(Rosetta, center, with blues greats. Photo by Barbara Barefield. Compliments of Rebecca Reitz)

The website also has material on Rosetta’s arrest on charges of

having an obscene window display at her bookstore in 1949. (The

local bishop complained.)

I interviewed Rebecca Reitz on April 15, 2020, by telephone at her

home in Manhattan.

DYLAN FOLEY: Rebecca, you have set up an impressive website as

a tribute to your mother.

REBECCA REITZ: I did it out of love. I made the tribute site because I

am eager for her accomplishments to have a record. There is no one I’d

rather talk about than Rosetta.

DF: When I interviewed Rosetta in 2005, I mostly focused on the

Four Seasons Bookshop. The store lasted for about six to eight years?

RR: That’s about right. First, they had it on Greenwich Avenue, then they

moved to 8th Street. Then her doctor advised her if she wanted babies, she had to stop working.

DF: Rosetta’s papers have been donated to the Jazz Archive at Duke

University?

RR: I was so lucky, they approached me, because I was forced to deal

with her business at the end. For the last couple of years, she didn’t have

the energy It was a godsend they wanted the

papers.

DF: When were your father Robert Reitz and Rosetta married?

RR: They got married when Rosetta was 23. My sister was born in 1953. She had me a year later.

DF: When Rosetta moved the store to 8th Street, she was razzed by

her bohemian friends for adding greeting cards.

RR: That was the business they did together. He drew the pictures and

she managed the business. Did her friends think it was too commercial?

DF: Was the 8thStreet store profitable?

RR: It was a success. They threw opening parties for authors. In those

days, you could make a living in the store. They bought the house in

Hackettstown, New Jersey. They were doing very well with the greeting

cards. They bought a house on Fire Island, in Seaview, near Ocean

Beach.

That was one of the big regrets, was when my parents separated, they

sold the beach house at a profit.

They shut down the Four Seasons, probably is 1953, when she wanted a

baby. My sister Robin was born in November 1953. She had three girls in

four years. I was born in ’54. Rainbow was born in ’56.

DF: Rosetta and your father Robert Reitz were in New Jersey for a

year?

RR: Oh, yes, then they moved to West 4thStreet and MacDougal. The

official address was 39 ½ Washington Square South. The entrance

was on West 4th Street. It was on the 3rd floor, a six-room apartment. It

was not that easy to find that size apartment in the Village. We lived there until I was about 10, when Washington Square Park, which was our backyard, started hosting all these runaways and drug dealers. Plus, the rent was high, as she was a single mom. At that point, we moved to Chelsea.

DF: When did your parents separate?

RR: I must have been about seven.

DF: Did your father stay in the city?

RR: That was part of the plan. First, he would come and tuck us in at

night. He got an apartment on Waverly Place. We’d stay there every

Friday night. We’d spend Saturday with him. That went on for a very

long time, until he moved down to Florida. He wasn’t like the older people in Jewish Miami because he wasn’t Jewish. He had a girlfriend down there.

DF: You moved to 16th Street at about 10?

RR: Yes, all three girls lived in one room. [Eventually], my father wasn’t

around. It was very tough. It wasn’t easy.

DF: How did Rosetta wind up at the Village Voice?

RR: In the early years, she wrote a series of columns called “Dining In,

Dining Out.” Her cooking expertise was one of her accomplishments.

She wrote the cookbook Mushroom Cookery. “Dining In” would be

recipes and the “Dining Out” would be restaurant reviews. She was

When she needed a job, she started to run the Classifieds, because she

had the business savvy. She hired a lot of musicians to run the desk. The Classifieds was where you got a job and got an apartment.

DF: Were there any colorful stories from the Classifieds?

RR: Sure. There were the Personals. Right next to the Personals was the

column “Pets for Free.” “Two free black pussies.” It was put in the wrong

column. That was a big one.

A lot of the people she hired were musicians who worked with the pianist and educator Cecil Taylor. A lot of students. Very very hip. They came in and worked for an hourly rate. She was the lady in charge.

DF: Was Rosetta hitting the jazz clubs?

RR: When I was old enough, I went with her. When I was a teenager and

when I was in college.

We went to large concerts, particularly the Newport Jazz Festival. The

New Jersey Jazz Society had concerts. We also visited another loft, the

Jazzmania Society on East 23rdStreet. We also went to the Cookery,

because Alberta Hunter was singing there, one of the old jazz ladies.

[[The Cookery was on University Place and closed in 1984]. We went to

the Village Gate and a place called Slugs, which was really funky. [Slugs’

(Village Gate, 1950's)

DF: Your mother was very frank about her sexual liberation. When I

met her in 2005, she told me that since she was political in college in

the 1940’s, she was fitted with a diaphragm. She was on the vanguard

of sexual liberation. The Village was a place where things happened

much earlier.

RR: That’s why people would move there. The people who moved to the

Village were interested in freedom. The sexual revolution

in mainstream America did happen in the ‘60’s.

To have a mother who was free, that was very unusual for a woman my

age. I am 65. Most of my friends’ mothers were virgins when they got

married. She was different.

DF: Where did Rosetta’s interest in finding the women blues

musicians come from?

RR: She wrote about this and it became one of her standard explanations was that when a woman came of age in the 1950’s, jazz belonged to the men and they would give it to the women.

For instance, she was a jitterbug and would dance to Benny

Goodman, like every girl who grew up in the Depression did. When it

came time to listening seriously to John Coltrane or Duke Ellington, in

those days, the man would reintroduce the record. If you read the ARSC

Journal interview, she talks about when she started exploring jazz, her

feminism coincided, of course, and she started looking for the women.

Where were the women? The women were there. She just had to find

them.

Did you ever hear of Studio Riv-Bea? Did you ever hear of Sam River’s

place, one of those jazz lofts in the 1970’s? Sam Rivers was this out

saxophonist. His wife was named Bea. Not only would Rosetta go to

these jazz clubs, she went to these other scenes. A lot of these kids she

hired at the Voice played at these other places. A lot of it was just

cacophonistic. It was not melodic. It was a scene. It was nice.

DF: How did your mother track down the women who were on her

albums for Rosetta Records?

RR: She belonged to various groups, like the New Jersey Jazz Society

and the New Jersey Record Owners. There is a certain quality of the devoted collector who is interested not only in the music but in the reissue numbers.

She knew the names of a lot of women she wanted to pursue. Then she had seen a lot of the women, like her “Women's Railroad Blues” album, the women singing about taking their men away, like a monster.

(Women's Railroad Blues, compliments of Rebecca Reitz)

In most black folklore, the railroad is seen like a liberator during the

Great Migration, to take the black person from the South to freedom.

She knew who were the main singers. She’d go collecting the 78’s from

the record fairs and if she found one with an unfamiliar name, she’d get

the record and listen to it. She was savvy enough to recognize its musicaland historical value. She had a list of names she pursued.

Rosetta didn’t reissue albums. She reissued songs and put them in

collections. Like with Ethel Waters in the 1920’s, they didn’t make

albums. They just issued various songs.

This was before the internet. She would make several attempts to contact the artist. With the International Sweethearts of Rhythm, she got to know some of them quite well. For instance, she put [bandleader/singer] Sippie Wallace in one of her shows. You’ll see a picture of Sippie Wallace with Rosetta when she was a really old lady on the Tribute website.

(Sippie Wallace, composer and singer)

There were some women Rosetta could find and some women she

couldn’t. It was all done by phone and snail mail. For the most part,

people loved having their music reissued.

DF: Rosetta set up a series of concerts with her rediscovered blues

women, including shows at the Newport Jazz Festival at Avery

Fisher Hall, Carnegie Hall and the Hollywood Bowl. Did you go to

these concerts?

RR: I worked them. They were a great experience. It was a full house and people really appreciated them. She had the most wonderful musicians. A lot of them were from the swing era, the sidemen. Dick Hyman was the musical director. He would set up the songs and the women would sing them. Some of them were the old ladies and some of them were contemporaries, like Nell Carter and Carrie Smith, a 1980’s blues-jazz singer. The older singers were Big Mama Thornton, Adelaide Hall and Beulah Bryant. It was a combination of the old ladies who were alive and the younger ladies interpreting their songs. It was swinging. Everybody loved it.

DF: Were you and Rosetta involved in producing the documentary

on the International Sweethearts of Rhythm?

RR: Nooo…that was the one we were going to produce, but it was stolen

from us. That’s a whole terrible story. It broke my mother’s heart.

There were these two women, Greta Schiller and Angela Weiss, and they

were filmmakers. They had done the movie, “Before

Stonewall,” about gay life in Greenwich Village before the Stonewall

Riots. They were progressive and they loved the Sweethearts, mainly because they were all women. They weren’t music people. We all working on it.

(International Sweethearts of Rhythm, compliments of Rebecca Reitz)

(International Sweethearts of Rhythm, compliments of Rebecca Reitz)

They used Rosetta to get all the history and we were all in the editing

room together. One day, we went to the editing room and the footage was gone. They said, “We are the professionals. You don’t know what you are doing.”

They got what they wanted, they got the introductions to the Sweethearts, the living ones, so they could interview them. They got all the connections and history and decided they didn’t need us anymore. They stole the project and put their names on it. It was a disgusting, disgusting thing. Rosetta never recovered from it.

Rosetta’s name is on the project, but it doesn’t mean anything.

DF: You’ve said that Rosetta lectured on women in films?

RR: She had a film collection of “soundies.” A soundie is a song clip on

film, a precursor to music videos. They had juke boxes where you would

put a quarter in and you could see them. Sometimes they would play

them before double features, like Fats Waller.

Rosetta had a collection of women doing soundies and clips of women in

films. There’s a full-length film called “St. Louis Blues,” and there is a

song that Bessie Smith is singing. She also had a clip of Billie Holiday

from a Nat Hentoff program, singing “Fine and Mellow”. She’d introduce the clips in a lecture formatand introduce them in an historical context. She produced a VHS collection of the film clips, too.

DF: How long did Rosetta Records last?

RR: She started it in 1980, when she was 56. The company went

until she died in 2008. The last record she produced was by Dorothy

Donegan, “Dorothy Romps,” in 1991. She continued selling and

promoting the records, and went around as a film historian lecturing.

Rosetta had a professional distributor and had her own mail order.

Libraries and schools also bought records.

There are two major reasons Rosetta did Rosetta Records. One of them

was to correct the history. It was political, because the women had been

ignored and she wanted to recognize them. The other reason was just a

pure love of music.

Rosetta was filled with a pure love of the music. Sometimes she might

come off as didactic, but she had a great sense of humor, and she had

enjoyed the love and the humor of the music very much. That’s what she

was giving as a gift to the world, in addition to correcting the history, that these women made an important contribution to the music. I wanted to make these contributions very clear.

DF: Did you have a lot of backstock?

RR: I did. Lots of vinyl and a lot, a lot of cassettes. Who wants a

cassette? I also had Rosetta’s whole record collection. It was a big

challenge.

DF: Did you donate the masters of the 19 Rosetta Records to Duke?

RR: I have the masters. Duke has her papers and photos and recordings of her on radio shows. The masters are for reproducing the records. Duke doesn’t do that. I keep these master tapes in a storage room because who knows what the future may bring.

If people are interested in listening to the music on the albums, they can find them as vinyl or cassettes and some CDs for sale around the Internet. Some have even been put on YouTube.

DF: One last detail from Rosetta’s life…Rosetta was a stockbroker in

the 1960’s when women were actively discouraged from being in that

business. How did that happen?

RR: She was sick of being poor. She wanted to make money. She thought

that would be a way to make money. She was a secretary at Merrill

Lynch. She studied and studied. It was hard. They didn’t like women

stockbrokers. She tried. It just didn’t work out.

2 comments:

This interview with Rebecca Reitz about her pioneering mother is wonderful and

inspiring, not only because it brings to life the remarkable achievements of Rosetta Reitz but because it shows how devoted her daughter is to her legacy.

Rosetta Reitz was a force of nature in the late 1940's, 1950's Greenwich Village, running her avant garde bookstore. She also was a pioneer in producing all-but-forgotten women musicians in the early days of the blues and jazz. Rebecca Reitz was a great source on her mother and very focused on keeping her mother's legacy alive.

Post a Comment