February 3rd,

2020 was the 75th anniversary of when the then-20-year-old B-29

navigator Edward Field’s plane was badly shot up by anti-aircraft fire during a bombing run over

Berlin. The plane lost altitude, fuel and two engines, but the heroic pilot managed

to ditch the plane in the North Sea, saving Edward and most of the crew’s life.

The pilot died of a mortal chest injury and a young tailgunner gave his life to

save Edward.

The poet Edward Field was born in New York City in 1924, the son

of immigrants from Eastern Europe. His father was from Lithuania and his mother

was from Poland. Edward was born in Brooklyn, but to pursue the American Dream,

his father moved the family out to Long Island, to Lyndbrook, which was

unfortunately the home of the German-American Bund, and young Edward was

subjected to constant anti-Semitic abuse by his schoolmates during his childhood.

His father was a distant patriarch and used physical discipline

with his six children.

Edward enrolled in New York University. World War II intervened

and become a sudden relief from his miserable family life. Edward shipped out

to Oklahoma. As he boarded the train, a Red Cross worker gave him a care

package, which included a book of poetry. By the time Edward arrived in

Oklahoma, he knew he was going to be a poet. Edward trained as a clerk typist.

To end a bad love affair with his sergeant, Edward volunteered for the Army Air Corps. Trained

as a navigator, he shipped out to Europe in the fall of 1944.

On his fifth bombing run over Berlin, his B-29 was badly shot up.

The pilot managed to successfully ditch the plane in the North Sea, saving the

crew but received a mortal chest injury.

There was not enough room in the first life raft, so Edward was in

the water. The tailgunner gave up his place, saving Edward, swam to the second raft, but died of hypothermia.

After the war, Edward did a short stint in Paris, then settled in

New York. Edward worked in a warehouse and tried being a Communist, then

supported himself as a temp typist.

In the mid-1950’s Edward had an affair with the poet Frank O’Hara,

who showed Edward what it was life to be a gay man without self loathing. They

remained friends and O’Hara promoted his work. Edward has at times been linked

with the New York School of Poets.

In 1959, he was working in a typing pool at an ad agency when he

was introduced to a handsome writer named Neil Derrick. They moved in together

after a few weeks, which started their 58-year relationship, until Neil’s death

in January 2018.

In the early 1970’s, Edward moved into Westbeth, subsidized artist

housing on Bethune Street in the West Village. Neil joined him in the next

year.

In 1963, Edward published his first book of poetry, Stand Up, Friend, with Me. Other poetry

books followed, including After

the Fall, A Geography of Poets, A New Geography of Poets, Counting Myself Lucky: Selected Poems,

1963-1992 and A Frieze in the Temple

of Love.

Edward published his memoir of his life in post-war Greenwich

Village called The Man Who Would Marry

Susan Sontag in 2005.

The interview took place in Edward and Neil’s Spartan studio on

November 3, 2016.

At the time this interview was published in February 2020, Edward

was 95. Recently, an animated short movie called "Minor Accident of War" of Edward’s bomber being ditched in the North

Sea has been gaining attention around the country at film festivals. Edward did the

narration with his poem “World War II,” chronicling the event.

(Edward Field in the 1950s)

Interview by Dylan Foley

EDWARD

FIELD: You heard what happened to my social security?

DYLAN FOLEY: You and Neil got married a few months ago?

EF: Yes,

they cut Neil’s social security, because my social security was added in. The

other day, we went to [Congressman] Jerrold Nadler’s office and saw a

caseworker. She wrote a letter to the VA from him about us. They cut his

pension by a third, about $300.

NEIL

DERRICK: They cut it by $400, Ed, from $1200 to $800.

DF: But you guys always lived cheaply.

EF: We’re

frugal. They wanted us to write down what the income was, and what the expenses

were. The expenses were bigger than the income because they cut it. I hope that

is significant. The overage on the expenses was exactly what they cut.

DF: You’ve always done most of what you wanted to do by living

frugally.

EF: We

live in luxury. It’s amazing. We travelled all over. We rent apartments in

London and Paris, and we’ve travelled to Amsterdam and North Africa. It’s been

a terrific life.

DF: Your parents were the original immigrants?

EF: They

were from Eastern Europe. My father was Lithuanian, but it was Russia at the

time. My mother was Polish. They must have been eight, and 10 or 12 when they

came over.

DF: They lived on the Lower East Side?

EF: They

went to the Lower East Side. My mother was in the garment industry for a while.

She modeled hats. She was very beautiful.

They

lived across the street from each other. One of my father’s sisters married my

mother’s brother. That was the first connection in the family. I think they

lived on East 7thStreet.

All the

old Indian restaurants nearby are going away. [Edward is referring to the

restaurants on East 6th Street.]

My mother

was 18. My father was 22 or 24 when they married.

My father

went to Cooper Union and the Art Students League for painting. I don’t know what

he did until he landed at MGM in their advertising department on Times Square.

That was his lifetime job, once he got it. Their advertising department was in

the Loew’s State building.

My father

moved the family out to Long Island. We were all born in Brooklyn, all the

children. It was Bay Park, right near Bensonhurst on the water. There was a

little boat basin. My father has a little boat. Then he was going out to the

real America, so he moved out to Nassau County, which was the headquarters of

the German-American Bund. Jews were not exactly welcome.

We grew

up before the war in Lyndbrook. They had a campground in the field behind our

house. All that was left was the flagpole. The Bund did meet in the high

school. There were swastikas on the telephone poles, graffiti.

DF: What was your father like?

EF: He

was an immigrant. He never became an American. He came over at 12. He didn’t

have an accent exactly, just a strong New York accent. He was an artist. The

family only had classical music we were not allowed to listen to popular music.

Every Sunday, we had a recital for him. We all played instruments. He sat back

as the patriarch and we would all parade out with our instruments. I played

cello. I never had a decent teacher.

There

were three boys and three girls. I was the eldest boy, but I had two older

sisters. They played the violin and the piano. We had a trio called the Field

Family Trio. We were on the radio a little bit. We were on WNYC, on the Horn

and Hardart Amateur Hour. We won a cup at Jones Beach in the family music

competition. We used to drive out to Freeport to play at WBGG. We had a program

called the Field Family Program and their Romantic Melodies.” 7pm. Dinner

music. It was a good experience.

DF: Did you go to local schools?

EF: Yes.

DF: What did you do when World War II started?

EF: I

went to work on a farm in the summer. They were short of farmworkers

immediately. I went to Peekskill, New Paltz, and worked on a farm for the

summer.

DF: What were your parents like?

EF: My

father was a European patriarch. He was a brutal man, but he himself had a

rough upbringing. His idea of raising children was to train them. You had to be

socialized. He battered us a lot. He was, I guess, just from his culture.

Parents were like that in the old Europe.

DF: He had a rough childhood?

EF: His

father left and his mother took a lover, so he had to hide in the house. He had

to hide behind the couch. I don’t know the details. Nobody will tell you.

To get

the real idea of what life was like before they came to this country, it’s very

hard. Most Jews don’t know what their parents life was like before they came to

the U.S. They were glad to escape the pogroms and the poverty. The ocean

crossing was amnesia. I’ve done a lot of questioning and I’ve got as much as

you can get, what life was all about.

My father

was from a larger town, a little more developed. My mother was from complete

peasants. They were business people. There were a few things that my father

told me that were unusual. One was that when the men had a political

discussion, they gathered in the local forest. Maybe they were discussing

socialism, which was criminal. He was sent to the edge of the forest, to warn

them if any Russian officers or soldiers came. That was interesting, like a

little image. You don’t get much of that.

DF: Why did your father change the family name to Field?

EF: Yeah,

to get into advertising. Before the war, a Jew couldn’t work in advertising.

DF: Why is your email “fieldinski”?

EF:

That’s what the kids called me. They used to say, “What are you?” They’d say,

“Go back to your own country.” My father said, “Say we are atheist Jews.” In

Lyndbrook, a Jew was an atheist anyway, because he denied Christ.

DF: Was this abuse in middle school?

EF: This

was grammar school. High school was much better. High school was much better.

The Army was a liberation. It was wonderful.

DF: Did you go to college before the military?

EF: I

wasn’t drafted. I had enlisted. I had to get out. My father said that I should

go to the College of Commerce at NYU and study advertising. I did that and it

was totally unsuitable, so I enlisted. My parents had to sign for me. I must

have been 18, but they had to sign. I can’t remember.

DF: Did you pick the Army Air Corps?

EF: I

did. Trenches and foxholes didn’t agree with me. First, I trained in Miami

Beach, on the golf course. They marched us out. It was quite a nice two months.

Then they put us on a train to send us to our next assignment, a

clerical school in Colorado. I already knew how to type, but they

gave me real training. I had a clerical job in Tinker Field, Oklahoma City. It

was nice. It was all new to me. The Army was great. I grew up in a town where I

was so despised. I guess I despised myself, as everybody despised me. Being in

the Army, I was with men who respected me.

DF: Why were you despised for being Jewish?

EF: At

first. we were foreigners and my parents spoke Yiddish. That was horrible. We

were marked for punishment. They beat me up all the time and for no reason.

Nobody protected me. Once, a big girl protected me. She kept the guys from

beating me up.

DF: When were you sent to Europe?

EF: I had

a boyfriend, a master sergeant in the barracks. We started an affair. I had

other encounters. I was an active teenager. You find sex everywhere. I did go

to the city for sex, but I also found it hitchhiking. Hitchhikers have a good

chance of running into sexual opportunities.

DF: Was there any danger to these encounters?

EF: They

were mostly positive.

DF: What happened with your sergeant boyfriend?

EF: He

moved me into his room in the barracks. He was an outdoorsman. . He used to tie

flies. Tough. One day, a group of the guys was having a bull session, and he

twisted my arm back. That’s what the kids did to me in school. It blew my mind.

From that instant on, I didn’t want anything to do with him. I was living with

him in his room, so I applied for the Aviation Cadets. An information sheet had

come over my desk. They were looking for cadets. I applied and became a cadet.

I didn’t get to be a flirt, but they made me a navigator.

DF: In an early poem, you wrote about being a clerk at 30,000

feet.

EF: I had

a machine gun at my window and I did fire it once.

DF: What happened to you in Europe?

EF: I

went there in the end of 1944. I was flying over Europe. I was stationed in the

Midlands. We flew mostly over Germany. Early 1945. I flew ‘til the

end of the war. They were B-17s, Flying Fortresses. They had a crew of about

nine. Sometimes we had a visitor, big brass or something.

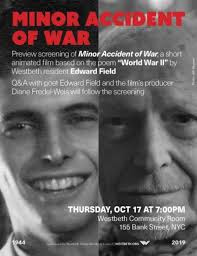

(Minor Accident of War, 2019...Edward's animated movie)

DF: You were shot down?

EF: It

was my fifth mission. It was over Berlin. It was February 3rd. I

just found a report of it online. There were lists of crew and if anything

special happened. They had a page for the guy who saved my life. It didn’t say

anything about him saving my life. He was never given a medal or anything. The

pilot got a silver star. He died. It was probably a chest injury. They have a

control panel in front. The landing was in the North Sea, which was like

hitting a brick wall. We were between Holland and England

You get

into the crash position against one of the bulkheads in the middle of the

plane. You sit backwards against it with your knees up, then a guy sits,

leaning against your knees. Then somebody sits against his knees. Then you re

like an accordion. I was against the bulkhead, so I got the full weight of the

crash.

DF: You made it to the raft?

EF: I was

in the water and there was no room. The gunner saved my life. I

actually wrote to the webmaster, to apply for a medal for him.

DF: Why did he give up his seat?

EF: He

was a very energetic kid, and I think he saw that what we needed to do was to

pull the rafts together. One was not completely inflated and taking in water.

The pilot was in there. He was out of it. This was in mid-winter. He saw that

he should get out, swimming and pulling the rafts together. I had read that you

can only live 20 minutes in the water.

DF: Did he die of hypothermia?

EF: Yes.

Another guy never got on the raft, as well. He swam for the second raft and

never got there. The water was deadly. The gunner took of his clothes to go in

the water.

DF: You were assigned a new plane?

EF:

Another plane and a new pilot. The crew stayed together. We lost five planes.

We didn’t get shot down, but we got shot up. The planes were junk. We landed on

an airfield once where the propellers weren’t even spinning. They were junk. I

guess they used them for parts. The German air corps was pretty well depleted,

though at the end they got jet fighters…if they had just gotten them sooner and

had enough gasoline. That was the one time I fired my gun. The jets would try

to break up our formation, flying between the planes. We flew wing to wing. The

German jets were much faster than regular fighters. When you used your gun, you

had to clean it after. I was so tired after 8 to 10 hours in the air, I didn’t

[want to clean my gun.]

(Edward in the US Army Air Corps)

DF: Did you have any romances in England?

EF: I did

discover a gay club in London. I had an affair with a gay captain in Paris,

just after the war.

DF: Was it dangerous to make or respond to overtures?

EF: I did

meet guys. All you had to do was to go to the chaplain’s assistant, who was

always gay. He was the contact on the base. Then there was a gay crowd at the

PX or at the bar. I met gays after the war. We were transferred to

the South of France, where there was an airfield. We flew American soldiers

going to the States over to Casablanca, and then we’d go back and get more. We

ferried big brass to Paris and Frankfurt. I went to different cities. In Paris,

I went to the most famous gay bar Le Boeuf sur le Toit, started by Cocteau. It

was a surrealist café. The bar was totally gay, with servicemen from all over

the world. They even said de Gaul had come in a few weeks before.

There I

met my captain. He managed to hitchhike to Southern France. He was actually

being courtmartialed for being caught in bed with a paratrooper. Mostly, it

didn’t feel very dangerous.

DF: During the war, was there a gay bar explosion in New York?

EF: I

think that’s true. They were packed for sex. Both men and women were going

there. Greenwich Village was known as a place where a man could get laid.

Greenwich Village was the home of free love. That’s what it was famous for.

DF: When did you come back to the States?

EF:1945.

I went to NYU. I met Alfred Chester there. I had to go back to the School of

Commerce. The rules said you had to go back to what you were doing before. I

took classes at the Washington Square College of Arts and Sciences. I knew I

wanted to be a poet.

DF: Was it the book of classic poetry the Red Cross women gave

you?

EF: As we

were getting on the train, going from basic training to my school in Colorado,

the Red Cross ladies were at the train. It was a long journey, three days to a

week. They gave each serviceman a little packet. In it was a toothbrush, a comb

and a paperback book. My book was Louis Untermeyer’s Anthology of Great English Poems. That’s what I read going on the

train to Colorado. When I got off the train, I knew what I was going to be, a

poet, though I had never written poems before.

DF: What was NYU like in 1945?

EF: In

the class was Cynthia Ozick, but I didn’t know her. She was in a

totally different world. I was not interested in a course on how to be a poet.

The thing about then was that you didn’t go to school to be a poet. You just

worked it out. Now everybody goes to these MFA programs.

At my

table was George W. Broadfield III, a black intellectual. He had a certain fame

at the time. He was the first black executive at Standard Oil. They didn’t hire

blacks, they didn’t hire Jews. My friends were thinking what to do, what job?

You calculated, could you get into medical school when there was such a small

quota for Jews. Like I couldn’t get into Columbia, because they had such a

small quota. NYU was open.

DF: Were you working?

EF: I

worked after school at Arnold Constable’s, where Mrs. Roosevelt shopped. We

sewed tags on dresses, we hung clothes on racks and pushed racks around the

store. I actually picked someone up there, a window dresser.

DF: Ah, the arty types!

EF:

(Chuckle.) At that time, I was commuting from home. People who were more smart

and sophisticated than me got their discharges in Europe and went to the

Sorbonne on the G.I. Bill.

DF: Was your mother a warm person?

EF:

She was a warm person, but she had so many children that she couldn’t pay

attention to each one. I realized later on that I was like my father and there

was a standoffishness. She really wasn’t crazy about me.

DF: Did she like your father?

EF: She

considered them friends. They must have liked each other. They had all those

children. They slept in the same bed. I once asked her why she had all these

children. Did she know about contraception? She talked about it all the time.

Margaret Sanger was like a goddess in her world. She said, “Oh, what do you

know? You’re in bed together and you roll on top of each other. You don’t plan

these things.” She was such a peasant.

DF: When did you move into the city?

EF: A

friend found me an apartment on the Lower East Side, a cold-water flat. It was

18 dollars a month on East 4thStreet.

DF: Were you still at NYU then?

EF: Yeah.

My father was horrified. You don’t leave home until you get married. It was a

shock.

DF: When was your first European trip?

EF: I

dropped out of college in 1948. I went to Europe. I met Robert Friend on the

boat going over. It was a converted troop ship. You couldn’t get a passenger

liner. Everything was organized in an economical way. The dining room was

alphabetical, so Field and Friend were next to each other. Robert has a job in

Pennsylvania, but dropped it and stayed in Europe. He taught soldiers until the

U.S, government threatened to take his passport away because he was a

Communist. The officer in charge of the teaching program told him the FBI was

there and asked him to get out. He went to Israel, where he lived the rest of

his life.

DF: How long did you stay at East 4thStreet?

EF: It

must have been a year or two. Then I moved in with a friend in Brooklyn

Heights.

DF: You dabbled with Communism yourself?

EF: If

you are really serious about Communism, you should become a poet of the people.

So I became a worker in a machine shop, then a warehouse. I had a union. I

loved the union.

DF: Where was the machine shop?

EF: It

was south of Washington Square, to the east. In the Victorian era, it was an

area of whorehouses. All the old buildings were factories. All that stuff is

gone. You couldn’t be a poet and a worker.

With

Frank O’Hara, his idea was that you just write until the phone rings, and that

is the end of it. You’re on the phone.

DF: You went into group therapy to become straight?

EF:

Partially, it was the fashion. Everybody was trying to go straight, because the

new therapies were promising it. The whole Freuduian ideal, if you believe in

the Oedipal situation, you wre made gay because you were blocked in certain

developments.. Killing your father and marrying your mother. Eventually, you

symbolically marry your mother. Of course, your balls have to want a

woman. If you don’t sexually want the other sex, it’s ridiculous.

We did

have friends who went straight. There was a particular bullying quality to the

group.

DF: Was it the therapist?

EF: The

members. They took the place of the therapist at most meetings. You had three

meetings a week and one meeting with the therapist.

DF: Was the order “Get a girl, get a job, get married”?

EF: You

get the job to get the girl. You can’t get the girl without money. You get the

job to get the apartment, then you get the girl. You have to be straight, you

have to be conventional.

This was

a socialist therapist. He didn’t believe in adapting completely to society,

because he believed that socialism was coming and all this would change. He

didn’t have this conventional idea.

I quit

because the analyst said to me, “Don’t you think you should write prose, so you

can make a living?” The idea was to get the apartment, to get the girl. I knew

he was not on my side

DF: Who was that older therapist, who showed up to your exhibit in

2006?

EF: She

came later.

DF: What was your experience after you met Frank O’Hara at the

Egan Gallery?

EF: I saw

you could live in New York as a gay. I also saw a different way of writing,

because he was so spontaneous. My training as a poet was New Criticism, where

you did manipulate the words until they fell into place. It took a lot of work.

Frank didn’t think that way. His mind was so sophisticated. I still don’t write

it out. I think he just wrote it out. I take more responsibility for what I do.

Second thoughts are not….

DF: What was the San Remo Café like?

EF: The

San Remo was one of the gay intellectual bars. I was not a big barfly.

DF: Did you know Jack Dowling early on?

EF: Jack

Dowling was a skinny guy. I had a friend who had a thing for skinny guys. He

chose Jack as the skinniest guy he could find. He went with the poet Ralph

Pomeroy. Jack woke up in a sea of urine. The bed was floating. Ralph was incontinent

when he was drunk. He got drunk all the time. [Edward gives me aquavit].

DF: How was Frank O’Hara as a boyfriend? Was he nice to you?

EF: Very

nice. He told me he would give money because I was so poor.

DF: Frank O’Hara had a job at MoMA?

EF: Yes.

He kept his money in a book and he showed it to me. It was funny when people

tried to pay me for sex, because some men automatically try to pay you. He was

going to support me. He was younger. He was so competent, so confident. To see

him living in New York. I had been in group, which cut off all my friends. You

live in group therapy.

I saw

Frank with a group of friends. He had a big, wide range of friends, who all

adored him. He had a place to live in New York with Joe LeSueur. He functioned

on his own. He wasn’t a neurotic child. He was living with who he was and he

was fine. He was close with Larry Rivers and Joan Mitchell.

Whenever

Larry Rivers was on his own, he and Frank were together. It was an on-and-off

again affair.

DF: Was there an incestuous nature to poetry reviewing in 1950’s?

EF: The

politics of the poetry world have always been that your friends promote you.

The group was small, the poetry world at the time, it was incestuous. Everybody

reviewed everybody else.

DF: Did you hang out with Frank?

EF: We

were always going somewhere or people were coming over. His social life was

intense. He never stayed home. He had to invent his way of writing poetry, for

there was no other time. I never saw him write anything. I never saw him

scratch a note down in his notebook like I did.

(Frank O'Hara)

DF: Did

MoMA play a role in your life?

EF: Neil

worked there. John Button was working there with Scott Burton, a whole bunch of

people who became famous.

DF: Frank O’Hara became paranoid? Did this end your relationship

as lovers?

EF: It

may have been a little paranoia. At the end of the summer—I saw him one

summer—he was going out to the Hamptons to stay with Larry Rivers or Fairfield

Porter, who was married. Before he went out, he said that he had put a

letter in the lockers [at Penn Station], and they had cleaned out the lockers

by the time he got back. He thought he’d talked about Larry and drugs in the

letter. He didn’t tell me, but I think there was a package of drugs in the

locker, too.

DF: Do you think it was pot or heroin?

EF: I

don’t think [Frank] did heroin. Everything was so small. It is so different

from now. There were little clusters of figures around each figure.

DF: Did you know Floriano Vecchi and his Tiber Press?

EF: I

have a set of the books. They are worth about $15,000.

Jane

Freilicher was a figurative painter. In Frank O’Hara’s world. They respected

figurative painting.

Herman

Rose—they liked him. I met him in Washington Square at an art show. He was at

the same psychiatrist I was. He was straight, but he was neurotic. I met him

through his wife Elia Baca. Everyone was neurotic then. It is

completely strange. It is completely gone now. In New York, everyone was

neurotic. I met his wife at an art exhibition in Washington Square Park. I

never saw her at the end. It was too much to take care of. We were very close.

DF: Do you know the Herman Rose and Franz Kline story? “You owe me

a screw.”

EF: It

couldn’t have been Herman Rose. He couldn’t pick up a woman in a bar.

DF: Did you see Frank O’Hara after you stopped dating?

EF: I met

him at the St. Mark’s Baths. He wanted to get together.

I did

have sex at the baths.

DF: What was happening with your own poetry in the 1950’s?

EF: I was

writing wherever I could. I would take a job, save a little money, then take

months off to write. Then I’d get another job. I once worked at an art

reproduction house, where I’d carry huge glass plates around. Artists would sit

at easels, painting the colors for reproductions There’d be one color on each

plate, then they’d put them together.

DF: Did you go to Yaddo in the mid-1950’s?

EF: I

went to Yaddo a lot. There were two important times. When I met Tobias, that

was the first time. Ralph was there, as well. Tobias had not yet gone to the

jungle. Then he went to the Yucatan, then Peru.

DF: You had a great description of Tobias, as walking like her was

walking through water. [His friend Tobias Schneebaum was a sexual

anthropologist, who lived in Westbeth and died in 2005.]

EF: He

walked so softly, it was wonderful. He was having an affair with a little tough

bantam rooster of a guy named Dudley Hupler. He would walk behind Dudley, a

tough little guy. Tobias, long and flowing, would follow him around. Dudley was

a painter. I’d pose for him sometime. I’d hold up my arm and he’d do a painting

of my armpit or just one buttocks.

DF: Was Dudley well known?

EF: I

guess not, but he sold a lot of porn. I think people took this as porn. It was

very erotic.

DF: When did you meet Neil?

EF: 1959.

He wasn’t working at MoMA yet. He got that job later. We were both working as

temporary typists, so we were sent out. At one job at an advertising agency,

they had a typing pool. They sat us together. We were talking too much. So they

separated us. Too late.

DF: Neil was living in the Forties, in Manhattan?

EF: West

47thStreet. Hell’s Kitchen. We lived across from the police station.

Q. What was the cop story?

EF: We

were arrested. We were questioned separately.

DF: You were harassed by an out-of-town cop?

EF: I

don’t know. I don’t know. He reported we were talking about the murder. Of

course, it was crazy. The police took him seriously. [out-of-town cop, comes

into New York to solve the murder of a family friend].

DF: Did you live together in Hell’s Kitchen?

EF: Until

we moved down to the Village. We had a neighbor who was very annoying. She was

really quite offensive.

DF: Because you were gay?

EF:I

don’t think that meant anything to her because she was a New Yorker. She made a

lot of noise. She had a huge family. Irish. She had huge parties. She had a lot

of friends and had huge parties with loud music. I couldn’t stand it. We moved

to the Village. You could get places to live back then.

(Neil Derrick in the 1960's)

DF: Where did you live in the Village?

EF: First

on Charles Street, in a furnished room, places that don’t exist anymore. There

were boarding houses. We lived there for a while, then Alfred Chester was going

away, so we moved to his loft. It was above the Sullivan Street Playhouse, near

Washington Square. I think it was “The Fantasticks.”

DF: When did your first book come out?

EF: Stand

Up, Friend, with Me. That was 1963. It was Grove Press, sort of an accident.

New Directions submitted my book for the Lamont Award, one year in 1962 or ’61.

(Stand Up, Friend, with Me)

The

next day, I asked Grove if they would submit my book. I guess they never

expected me to win it. When I won it, it was a little embarrassing for them,

but they published me, as required for the prize.

Neil and

I went to Europe, then I won a Guggenheim while we were there, so there was

plenty of money.

(Edward and Neil in the last decade)

DF: The Guggenheim came after the book and you had applied for it?

EF: Yes.

I guess so. It was $4,000, a princely sum. It really gave us freedom, because

we had gone on very little money.

DF: Where did you go in Europe?

EF: We

were in Paris mostly, but we also went to London.

DF: Then you went back to New York?

EF: Yeah,

then Neil got the job at MoMA. He was at the front desk.

DF: What was Neil writing at the time?

EF: He

was writing at the time, too, publishing his soft-core pornography. Recently, I

saw one of his books for $50 online.

DF: Did you do any teaching?

EF: I

finally decided to say yes [to teaching]. A poet published an article in the

Tampa Bay Whatever Times or whatever, where he wrote about calling me up to be

a poet-in-residence at Eckerd College in St. Petersburg, Florida. He wrote that

I said, “I’ve just decided to say yes to everything.” That was the idea to the

article, to “Say yes to everything.” I had. I finally decided, after I was a

poet and didn’t do anything else. I got the job translating the Eskimo poems. I

got an offer to be the poet-in-residence, and I accepted it. So I went to

Florida for a term. I did other things for a while. I had started to give

readings and went on tour. My analyst said, “Aren’t you going to sell your

books?” “Sell my books?” I said. “I’m a poet. I don’t sell stuff.” “Take your

book and sell it,” she said. I realized it was the most fun part of the

experience. I’d put a box of books on a chair with a price. They’d take a book,

leave money. I’d come back from the reading. There’d be money, but no books.

DF: Tell me about your analyst.

EF: I

went to her for seven years. She was pro-gay. She’d been in show biz herself.

She was 10 years older. She died soon after my 2006 book launch. When I met

Neil, I took him to her. She gave us her approval.

DF: When did you move to Westbeth?

EF: I was

in the second group. It was 1972. Neil and I had broken up. I told

the manager, I’m going to have to leave New York if I can’t find an apartment

here. He said, “That’s what were are here for, to keep artists in the Village.”

He gave me an apartment. It was three before this one. This is the third. It is

the most Gimuctisch. [The most livable. It’s German for livable.] We’ve been

here for 10 years.

We were

on the 5thfloor for a long time. It was like a cave. The first

apartment turned out to be noisy. It was driving me crazy. When they offered me

the cave, which was on a little courtyard, it was quiet. I healed from the

noise. When you suffer from noise, it is, it is a really terrible disease. In

the cave, I healed. I can’t remember if Neil moved in there.

DF: I’ve known you since 1998, when I did the piece on Tobias

Schneebaum. You were here already.

EF: I

have no sense of time anymore.

DF: Tobias was such a good soul.

EF: What

a terrific guy, terrific person.

DF: When did Neil lose most of his sight?

EF: About

’71 or ’72 We got back together, of course. There was no question.

DF: Had you started writing together at this point?

EF: He

couldn’t write. I helped him and we started writing together. Finally, we had

to stop. We did publish two novels, The Villagers and The

Office. It was difficult. You have your own ideas and you are too

strong-minded. Even living together is a victory.

DF: You have a poem where you recount the story of your mother

telling you not to marry a non-Jew.

EF: She

said that they would call me a “dirty Jew,” which was what the kids called me

in my childhood.

DF: That’s so awful.

EF: I

survived it. The thing is, my childhood was horrible, simply ghastly, because

my family was difficult, too. My life after that, when I think back, what a

terrific life I have had. I really have no complaints at all.

DF: You’ve done everything you’ve wanted to do?

EF: And I

am the nurse type.. If I have to take care of someone, that’s great.

DF: Do you find you have some understanding for the kids

who bullied you in school?

EF: These

kids were acting according to their parents. Their parents put that in them

because it was a Republican town. It was really a fascist town. Their parents

never would have hurt me, but the kids got it from their parents.

There

were very few Jewish families. The town was English, Scotch-Irish and German,

heavy German. They were innocent. It was from their parents.

We were

the blacks. They looked on us as the blacks. America was full of racial issues.

Eventually, the Jews became white. I am a Semite. I never think of myself as

white.

DF: What was the turning point for Jews and other ethnics when

they came into political power and prosperity?

EF: I

stopped getting flack for being Jewish when Israel was founded in 1947. No

matter what I think about Israel now, I think it saved my life.

When I

was a kid, they said, “Go back to where you came from” I had nowhere to go.

Everything

was different before Israel. After the war, Israel was founded It was a very

heroic little country. Even though we don’t think about what they’ve been doing

with the Palestinians. Nevertheless, it saved my life. I look at what Israel

has been doing and its horrible. The reactionary religious Jews have taken

over. It’s not socialist kibbutzism anymore.

I am also

glad we’ve been back to Muslim countries. I went to Afghanistan by myself.

DF: After the first book, did you find more success as a poet?

EF: There

is the Geography of American Poets. I did the anthology.

DF: How many books have you written?

EF: I’ve

only had nine books of poetry and prose. I do hope to get my collected poems

done eventually.

(Counting Myself Lucky)

DF: What year did you start writing?

EF: It

goes back to 1949, when I started writing what I thought were good poems. I

look over my collected poems. I have a file. I thought, “Gee, these are terrific.”

DF: What was Westbeth like in 1972?

EF: It

was an industrial neighborhood, and shipping, the docks. There was a big sex

scene in the trucks of the waterfront, and on Washington Street, right in front

of Westbeth. There was a lot of cruising and drag queens. There were cars

cruising by to pick guys There was a rabbi driving by with Jersey plates. It

was very funny. Before you go home…

I read

that there were these guys at the Holland Tunnel, picking up men who drove to

New Jersey. It was a financial transaction. Penn Station was a good place for

pick ups. You could pick up guys before they went home to their families. There

were little hotels nearby. In New York City, there is sex everywhere. If

you want sex, you can find it everywhere.

DF: Was the area around Westbeth dangerous?

EF:

Never. We did have friends who were mugged. A woman in my building, who’d been

in one of my group therapy sessions, two drag queens came up on either side of

her and said, “Take us to your bank machine and we want you to withdraw money

for us.” She died soon after. That was a big shock. She was a fervent

communist, so blacks were sacred.