(Historian Lisa E. Davis)

The historian Lisa E. Davis was born in Georgia in 1941 and was educated at the University of Georgia, where she did her PhD in Comparative Literature. She escaped to New York in 1966, then lived and worked on Long Island, at SUNY Stony Brook. In 1974, she started working at York College, CUNY, in Queens, and moved into her apartment on Charles Street. She never left.

As a young historian in the 1980s, Davis began to organize thoughts and memories of several older lesbians who had been her friends on Long Island. When they were younger, the Village had been their hangout, and some had worked and performed at mob-nightspots like the 181 Club and the Club 82 in the East Village. Their stories inspired the first book Lisa Davis wrote, Under the Mink, published in 2001. It is a novel set in 1949 in the drag bars of the Village, with a murder story, a romance, and violent mobsters winding their way through it. The novel was reissued in 2015, with photos from the author’s collection, and is a modern lesbian classic.

Her second book, Undercover Girl: The Lesbian Informant Who Helped the FBI Bring Down the Communist Party, published in 2017, grew out of another important Village connection. An interview that Joan Nestle of the Lesbian Herstory Archives did with Buddy/Bubbles Kent, who had performed as a chorus boy at the Club 181 in the 1940s and later in her own strip act, as Bubbles, was the key. Buddy, who had changed her name early on from Malvina Schwartz (of East New York, Brooklyn) because nobody was hiring lesbians or Jews, made an offhand angry comment during her recorded interview about a lesbian named simply Angie, who had been an informant for the FBI in Greenwich Village during the 1940’s Red Scare in America. Further investigation by Davis revealed the complex story of Angela Calomiris, a wannabe photographer who destroyed the career of a lesbian police officer and the lefty Photo League. Davis found Angela’s personal papers, as well as her FBI file, and became friends with Buddy, a remarkable character from the Village of yesteryear.

Under coronavirus lockdown, I spoke with Lisa E. Davis by telephone from her apartment on Charles Street in Greenwich Village.

DYLAN FOLEY: How did you wind up in New York?

LISA E. DAVIS: Darling, I was born and raised in Georgia. I wish I’d done my PhD at Harvard or Yale. Those are the only two places that matter. But I did not. I did my PhD At the University of Georgia in Comparative Literature, under something called an NDEA Fellowship, the National Defense Education Act. They started that when the Russians put up Sputnik, because they were afraid. I look at these children who owe $60,000, $100,000 or $200,000 for some bullshit degree that will never do them much good. In my case, the NDEA paid for everything, and this was Comparative Literature, which wasn’t particularly useful against the Russians. The government paid for degrees in everything because they could.

DF: Was it a Pentagon program?

LD: What I did had nothing to do with the military.

DF:When did you finish your PhD?

LD: That would have been in the Year of our Lord and Lady 1969. I was born in 41, so I must have been 28. I had free graduate school.

In Georgia, I was born and raised in the last years of a slave society, for that is what it was. If you have any kind of a brain, you can’t miss it. Slavery is part of the American way. We just don’t talk about it

DF: Your specialty is in Spanish and Latin America?

LD: Yes. I had a very good teacher. He taught in the Army Language Schools. He knew how to teach. I know how to teach, too. I just never had the chance. When you have 50 students at 8 a.m. in Jamaica, Queens, you are not going to get much done. They were nice people, wonderful kids. That was York College.

I did the PhD in Georgia. The original job that I got was at SUNY Stony Brook. I had worked in an NDEA language institute with the man who the department chair. That’s how you get a job.

DF: Did you move straight to the Village?

LD: I was on Long Island. The most bizarre experience of my life. That’s where the school was.

DF: When did you move into the Village?

LD: 1974. I moved into this apartment. That’s where we are sitting now. It’s on Charles Street, which is between 10thand Perry.

DF: Were you out at this point?

LD: Oh, for years. I’d been out since I was 16. I came out at the Women’s Missionary Society Camp one summer. The missionaries were sort of queer. That’s the Southern Baptists, who are opposed to everything.

DF: What was your social life?

LD: I was coming from the trauma of not having gotten tenure at Stony Brook, for diverse reasons, including the fact that my friend who got me the job was no longer there.

The woman who was heading the department at York lived across the street. I had been entertaining her and as soon as I accomplished my seduction, I got the job. It’s not only the boys who do it. While I was visiting her across the street, there was a sign that said, “Apartment for rent.” I took a look. It was the same money I was paying on Long Island. And it had an elevator. Of course, I remember the rent and I tell everyone. All the young people ask. Three and a quarter, $325 a month. It’s a one bedroom. It has an indoor toilet. I took the apartment. Now they are $4,500 a month.

DF: What was your social life like in the 1970’s?

LD: Was I alone? I’ve always had somebody. I had a girlfriend in Brooklyn. I was on the train to the Village and Brooklyn, then I had to go to Queens to work. A lot of my social life was on the MTA.

There were numerous lesbian bars in the Village, though most are long gone.

(The Duchess, formally at 101 7th Avenue)

(The Duchess, formally at 101 7th Avenue)

There were places like the Duchess, the Cubby Hole, which has changed locations, and the Fat Cat. There were many places to go. It was not expensive. You could get drunk and try to pick somebody up, which was the idea, of course. And Henrietta Hudson has survived, over on Hudson Street.

(Stormy DeLarverie, legendary Village figure who protected other lesbians, in front of the Cubby Hole, 1986)

DF: Was there a bar that suited you better?

LD: When it was open, Bonnie and Clyde’s on 3rdStreet was the loveliest. It was not there forever, but it was there for a while. Maybe it lasted 10 years. The Duchess was nice but there was some big thing with Ed Koch, who was always coming out of the closet to knock people around, and they closed the Duchess.

(Bonnie and Clyde's, 82 W. 3rd Street)

Bonnie and Clyde’s was very nice, and they had a restaurant upstairs that brought in a lot of people.

DF: How did you see the gentrification of the Village?

LD: A good friend of mine survived the AIDS epidemic. I am not sure how he did it. He said there were so many apartments available for these new arrivals because so many guys had died. It would be announced that So-and-So was sick, and then 2 or 3 days later, he was dead.

St. Vincent’s, now overpriced co-ops, thanks to Bloomberg and Mr. Rudin, and probably the people at Long Island Jewish Hospital/Lenox Hill… St. Vincent’s was one of the first places to take AIDS patients. Others wouldn’t take them, but the old nuns at St. Vincent’s took them in. People were terrified, but it is nothing like now, when the terror is real. You got AIDS from having sex. The latest virus is evidently free to all just by breathing.

(A striking Buddy Kent, left, late 1940's, early 1950's)

LD: Buddy/Bubbles became a good and dear friend, and I often went to the SAGE socials that she managed when SAGE was at the Center on 13thStreet. By then, she was working at St. Vincent’s as an x-ray technician until her retirement. She had a little training in photography during the war when she was in the Women’s Army Corps. She lived on 8th Street, right across from the old Whitney Museum. It’s now an art school that has been there for 100 years. The original Whitney was there, because it was in their backyard. Buddy had lived there forever, so she could afford to live there.

She took the name Bubbles when she got her strip act. Before that, she worked as Buddy. But she adopted the name Kent early on, because it was hard to get a job if you were Jewish, much less a lesbian. That was in the 1930s, 40s. Her family liked the name Kent, so some of them adopted it, too.

(Buddy/Bubbles Kent, had a strip act, where she'd go from male drag to lingerie)

DF: What inspired you to write Under the Mink?

LD: Ah, Blackie…what inspired me was that I quit teaching. When people ask me, I say that it is a work of historical fiction, in the style of Sir Walter Scott. Most everyone is completely identifiable. They are not made up. Generally, the heroine was a composite of several people, who did that sort of thing. The rich girl from uptown is a composite of rich people who come downtown, because many people came down to see the queers. The drag shows were very popular. It wasn’t a gay audience. It was generally a straight audience, mobsters, high society and show people, plus the bridge-and-tunnel crowd. Put a little excitement in your life, come down to the Village and see the performers! These stories were told to me by people who actually did it. They are all dead now. I am glad we kept some of that world alive.

(Under the Mink, Lisa E. Davis' novel, inspired in part by the life of Buddy Kent and her old friends)

I put my bar on 8thStreet. It was really the181 Club at 181 2ndAvenue. I put it on 8thStreet because I wanted to keep it in the Village. I used the Bon Soir address, if you remember the Bon Soir. Barbra Streisand had one of her first performance gigs there.

Speaking of the change in the Village, 8thStreet used to be a street of lively shops and clubs, and the first movie house in New York City, the first venue dedicated to showing movies.

8th Street was a street of dreams. Now it is “Retail Space Available.” Little things are beginning to open up, little restaurants and urgent-care centers.

DF: Is the movie theater the old Eighth Street Playhouse?

LD: Yes, that’s right.

DF: Did you do other research on the Village in 1949?

LD: I read a lot of stuff. A great deal of it was based on talk. Whenever the girls got together, my older friends, the “old broads,” as they called themselves, they loved to talk about when they worked for those Mafia clubs on 8thStreet, on 2ndAvenue, the 82 Club, down the street in the East Village—when it was still the Lower East Side—on East 4th. All run by the Mafia.

The 82 Club and 181 Club were run by Anna Genovese.

I got a second edition of Under the Mink from some crazy people I know. I didn’t have to pay, which was good. The new edition has photos. There are photos at underthemink.com.

The hookers at the 181 were very involved with the operation. Many of them were dating the girl performers. Madame Lucille in the novel was Lucille Malin. She was real. She was married to an old drag queen named Jean Malin who unfortunately for him drove his car off a pier in Venice Beach, with Patsy Kelly and another friend in the car. Fortunately, they survived. He did not. He drowned. He was quite young. He was a big drag performer in the 1930s. Lucille and he were a couple of sorts. Lucille was the biggest madame in New York. Her girls got around.

(A new clipping of Angela Calomiris, on her "Red Scare" testimony)

DF: Could you tell me about the Photo League and Angela Calomiris’ work with the FBI to shut it down?

LD: Probably her destructive capabilities were exaggerated because the forces that were after the Photo League were there from the beginning.

The Photo League members were taking pictures of poor people. They had a project up in Harlem that was a no-no. I have complete FBI files on many of the major photographers of the era, who were being watched for 25 years. There was Margaret Bourke White, a big lefty, and Ben Shahn, who made the mistake of being Jewish. I keep trying to give them to somebody. I’ve been in contact with the Tamiment collection at NYU but their archives are in transition and there’s no response.

(LIsa E. Davis' Undercover Girl)

DF: Your Undercover Girl project started with Buddy/Bubbles making an angry comment about Angela betraying s lesbian cop and forcing her to be fired?

(LIsa E. Davis' Undercover Girl)

DF: Your Undercover Girl project started with Buddy/Bubbles making an angry comment about Angela betraying s lesbian cop and forcing her to be fired?

LD: Exactly. The reason I got on to this was because of Buddy/Bubbles. She was so cute and was a good-looking gal ‘til the day she died. She’s been dead for quite a while. She spoke in rather mysterious terms without naming names. One of the rules back then was that you did not name names of other gay people. That was the kiss of death. You did not show them in your photographs. I have many photos of entertainers. It is very frustrating because they cut the other people out of the photographs. Only they appear, and you don’t see the other people.

Buddy/Bubbles was talking frankly about the early days, and suddenly made a connection between the subject at hand and someone named “An-Gie Calamares.” It sounded important. Then I found, also rather by accident, information on someone called Angela Calomiris. Check. These must be the same person. I called up Joan Nestle, who by then had fled to Australia. She said, “Oh yes, we have her papers at the Archives. Just tell them. They’ll get them out of storage for you.” [Editor’s note:The legendary lesbian writer and memoirist Joan Nestle was a co-founder of the Lesbian Herstory Archive in 1974, now based in Brooklyn.]

(Catalog for the Jewish Museum's exhibit on the Photo League, the leftist organization that Angela Calomiris helped destroy through her 1949 testimony)

DF: Buddy was implying that Angela used her contacts to destroy the career of a lesbian cop?

(Judy Holliday, the Broadway and Hollywood star, whose lesbian police officer lover was ensnared by the "Red Scare" in Greenwich Village. Holliday was also harassed by the FBI.)

(Judy Holliday, the Broadway and Hollywood star, whose lesbian police officer lover was ensnared by the "Red Scare" in Greenwich Village. Holliday was also harassed by the FBI.)

LD: Her name was Yetta Cohn. Yetta Cohn was a well-known Village person. She was also Judy Holliday’s girlfriend, for quite a while until Judy became better known [Editor’s note:Judy Holliday later became a well-known Broadway and Hollywood actress. She was investigated by the FBI herself for left-wing sympathies.] She played the Village Vanguard with a group called the Revuers that was kinda leftie, but everybody was leftie back then. Judy went on to greater things but died young at 43. She had been called to appear before something called the McCarran Committee, that investigated arts and culture, and the stress took its toll.

Angie did what she could to make it worse. The FBI may have been after Yetta previously but Angie chatted up her FBI connections. She chatted up the NYPD, saying that Yetta was a Henry Wallace supporter, the Bernie Sanders of his day. Wallace was Vice President under FDR. He was too radical. That’s when they put in Truman, the guy from Missouri. Angie ratted out Yetta and Yetta lost her job. She had been editor of an NYPD newsletter. She was not a policewoman walking the beat.

Another old Village person who knew Yetta said that Yetta had gone a long time with no work and had practically had a nervous breakdown. Judy helped her out, of course.

When Angela died, she died in Mexico, where she had some property, where a lot of expats have property. She couldn’t breathe. She thought she could breathe down there, better air. But she died anyway. She left all these papers behind because she had kept everything from her FBI years. This was the high point of her life. She was a star. What do you do with the papers? You either toss them or give them to the Lesbian Herstory Archives. Which is what the executors of her estate did.

Because I made that connection, I could write that book. It’s an important book because it shows what happened in America, when it drifted radically from left to right, and how the drift was engineered.

DF: There are so many levels to the book—the 1950s Red Scare, the FBI’s harassment of suspected communists, and attempts to destroy unions and leftist organizations like the Photo League. Then there is the story of Angela’s hard luck childhood living in a New York orphanage, her life as a closeted lesbian and her very public testimony on behalf of the FBI.

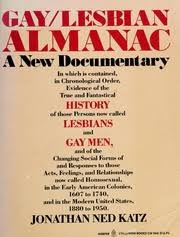

LD: I think that it was a quote from [the historian] Jonathan Ned Katz’s mother, who said here was an obvious lesbian up on the witness stand. In fact, everybody knew and the people who worked with her in the FBI knew that she was a lesbian. They needed her because she would testify. It was all about the money. The money was great. It was the best job she ever had.

DF: Angela sold out the members of the Photo League for $180 a month from the FBI. What influence do you think Angela’s childhood had on her life?

LD: What you said about the orphanage was true, and she was there for her entire adolescence. She was destroyed as a human being. She always told people that her mother was dead, and she was not dead. She would never live with her mother ever again.

Then there was the question of money because, of course, she had no money. One of the great ambitions of all the women that I knew, the old broads, and that included Buddy/Bubbles and Angela Calomiris, was to go to college. Then Angela would have a real chance at some kind of a job. Towards the end of her life, she managed to insert herself into a college program, but it was too late to make a difference.

The Photo League was her salvation because they provided very inexpensive classes in multiple aspects of photography. Something like $15 for six months of classes. “Come to the Photo League and learn how to make photos.” She was working as a photographer but not making much. Living in Greenwich Village, where rents were $30 a month, $40 or $50, she could survive. $180 a month would have been a lot. The offer from the FBI would have been too good to turn down because the money was great. After all, it was her government. It wasn’t Moscow. It was a patriotic thing. Well, why not?

The FBI terrorized anyone with a brain. Nowadays, they don’t have to hire informants. They have all these electronic devices. The computer has made informing much easier.

DF: How did you find Angela’s FBI file?

LD: I received Angela’s file from a woman—otherwise I could not have done the book—from Veronica Wilson who had done her PhD dissertation at Rutgers, on informers, with a focus on gender. “Red Masquerades: Gender and Political Subversion During the Cold War, 1945-1963” That’s what people engaged in serious research do, if they have access to FBI files, because they are very hard to get. They let other people copy them.

I have Angie’s FBI file, which is unbelievable. Then I have all the papers she left. I couldn’t have done it without her FBI file.

DF: Was Angela Calomiris difficult to write about?

LD: She was not a pleasant person to write about. She was not heroic. This was a great problem for people who knew her in P-Town. [Provincetown, MA, on Cape Cod.] I took the book to P-Town. The publisher, who I never would have gotten on my own but I got through somebody I know, is in Massachusetts. I did a run in Boston, then I went to P-town, where I had large audiences. Generally, the younger people were very interested, but there were old broads who knew Angela, who didn’t like the book at all. She had been their friend, somebody who had opened up P-Town to the lesbians. In P-Town, it was all about business. She ran one of the largest rental complexes in town. I know how she got that, by cheating some poor soul. He got into contract, he wanted to get out and she wouldn’t let him out. She got the property or $13,000 or $16,000 and sold it for millions. That’s real estate. She knew how to play the game.

Some of the women in P-Town said that I was demeaning lesbianism. I was always happy to explain to them if they wanted to meet some bad lesbians, I could introduce them to some of my exes. If they’d never met any bad lesbians, I’ve met quite a few who would take your money and whatever.

Angie was a very twisted personality who served the purpose of a very twisted time.

She became the lover for several years of the sister of her FBI recruiter. They owned a house in Connecticut. Angie made money she never would have made. If you are going to make money in this system, that’s how you make it.

DF: Are you still in touch with Joan Nestle?

LD: Joan Nestle is still with us. Her health is very good. She’s 79 or 80. She’s in Australia. They have National Health.

DF: Are any of the women you knew who come up in the 1940s and 1950s Village still around?

LD: The old broads I knew are all gone, but whenever they got together—and that would be 20 or 30 years after the fact—the most fun thing for them to talk about was when they worked in those [Mafia] clubs.

They would at least be in the opening number and the finale. Someone I knew was a stripper and played the downtown clubs. She didn’t get much retirement from stripping. She didn’t have much money. They were all living in West Palm Beach, Florida, in a trailer park. At least they had a roof, and that’s what they would talk about, and they would show these photographs. Sometimes I would be able to get a few. On the last visit to them, I found photos in a garbage pail. One friend said, “Nobody cares about that anymore.” I took them out of the garbage, but a lot of stuff was lost. Nobody filmed and you didn’t record. Photography was a big thing. It was big business in the nightclubs. They took photographs, developed them in a hurry, came back and sold them to the customers.

A lot of people had fun. When Joan Nestle was interviewing Buddy/Bubbles, she knew nothing about Buddy’s career. She was interviewing her because she was in SAGE. In the 1950s, early 60s, Buddy and a friend owned a Village club called the Page Three. That was Jacquie Howe. The guy at the end of the bench was their agent Kiki/Kicky Hall, who had a drag review he took around the country.

DF: How many years did you spend on Undercover Girl?

LD: Only 10 years! I discovered this story through Buddy Kent, otherwise no one would have known. The Photo League knew Angela was a lesbian. Some thought she had been blackmailed into testifying, like so many gay people back then. Perhaps they felt sorry for her and hated her, too. They were certainly horrified when she appeared on the witness stand to testify against the National Board of the American Communist Party.

The FBI knew Angela was a lesbian and didn’t care. They took anybody who was useful.

DF: Angela’s testimony destroyed the life and career of her mentor, the photographer and Photo League head Sid Grossman. What happened to him?

LD: Sid never worked in New York again. That’s what happened when you were outed. You didn’t work. He went to P-Town. He and his wife would fish all day and sell their catch on the street. That’s how they stayed alive. [Editor’s note:Sid Grossman died in 1955 at the age of 42.]

DF: Do you know where I could find other lesbians who were involved in the 1960s bar culture? Should I try SAGE?

LD: I’ll be glad to try to unearth some people. They have a problem with SAGE, because of the trans thing. All the women at SAGE suddenly became trans women. The lesbians were feeling marginalized but maybe they’ve worked that out.

DF: What do you think caused the decline of the lesbian bars in the West Village?

LD: They were all mob bars. If it wasn’t for the Mafia paying off the cops, there wouldn’t be any gay bars anywhere. It was all supposed to be illegal.

The Sea Colony [on 8thAvenue] was Joan Nestle’s specialty. She wrote about it and spent part of her decadent youth there. [Editor’s note:Nestle wrote an excellent essay on 1950s lesbian bar culture called “The Bathroom Line.”]

I think the increasing rents were very damaging. There was also some big scandal at the Duchess [at Grove Street]. Ed Koch was reigning then and they were always cleaning up New York. [Editor’s note:Ed Koch did succeed in closing down The Duchess, pulling the liquor license through using antidiscrimination laws.]

DF: Did social changes in the Village affect the bars?

LD: I suspect having the Gay and Lesbian Center there on 13thStreet was a great boon to a lot of things socially and politically because it gave people a place to go. The LGBTQ center has become more and more gentrified, I suppose. Back in the day, it was very popular and open. They didn’t charge money. Now they charge for everything.

People may have had other things to do besides going to the bar and trying to pick someone up. Maybe they could pick them up at a political meeting. Always at the AA meetings.

DF: Are you working on anything?

LD: I have a performer I would really like to do more on than I may be able to do. I can’t get the papers and photos she left away from the cousin she left them to. Cousin Joan got everything that belonged to a performer named Blackie Dennis.

Blackie was a nice Italian girl from a nice Italian family. She grew up in East Harlem. Like all the girls from her generation, she knew that you came to the Village. That’s where you came. In the 1930s and 40s, the Village was the center and that was because historically the Suffragettes had set the tone. It was a very female, politicized setting, and had been for years. Many of the Suffragettes were a little queer. Who else had time to do that kind of thing and get locked up?

Blackie Dennis was one of the women who found her way to the Village. She performed in several places. Things got hot down here because they were going after the Mafia. The clean-up committee was trying to eliminate the Mafia in the 50s. The Mafia was supporting the gay bars and prostitution. Drugs came into the picture later.

Blackie was working at the Moroccan Village on 8thStreet. There was a shoot out there She was also named in a very important trial about prostitution, though they did not call Blackie a prostitute. One thing led to another and she decided to work out of Miami, another hot spot for gay nightlife. The mob kept everything working very well. She stayed there with her girlfriend, the stripper.

Blackie dressed like a guy and looked like a guy. In late adolescence, she wound up in the Village. There is no recording of her voice, but she must have had a nice voice, because she sang all over the country. She had a singles act. That’s the next person I’d like to write about.