Close Read #2: How I Became Hettie Jones by Hettie Jones

By Dylan Foley

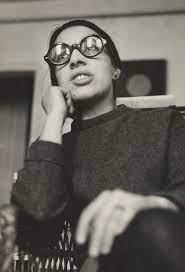

How I Became Hettie Jones is the memoir of a Jewish working-class woman from Laurelton, Queens, who after college moves to Greenwich Village in 1958 to become a liberated woman and a writer. Hettie Jones turns her back on the traditional expectations and immersed herself in the bohemian scene of the Village bars and poetry readings.

While working at the audiophile magazine Record Changer, a very dapper, handsome African-American man named LeRoi Jones comes in to apply for the job of shipping clerk. After several weeks of working together, the sexual frisson becomes unavoidable. The two very attractive, diminutive people become lovers and LeRoi moved into her tiny flat on Morton Street.

LeRoi came from Newark and was educated at Howard University. His parents are more middle-class, his father a postal carrier and his mother a community activist. LeRoi had just been thrown out of the Air Force for his political views and for reading the political magazine The Partisan Review.

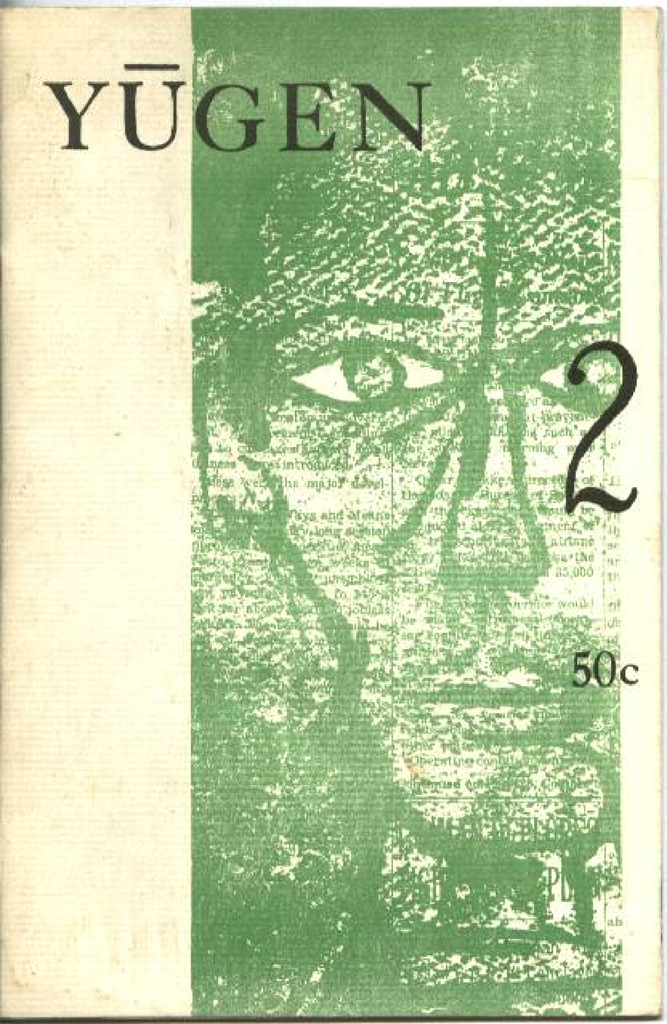

How I Became Hettie Jones is the story of Hettie’s seven-year marriage to LeRoi, and the turbulent sexual and racial politics of the late 1950’s, early 1960’s Greenwich Village. LeRoi and Hettie had a passionate love affair, while founding the poetry magazine Yugen and the Totem Press, which published Beats like Allen Ginsberg and the New York School Poet Frank O’Hara. They also held large, wild parties in their apartment in Chelsea.

The couple had two daughters, but the marriage was plagued by infidelities. LeRoi slept around and had a long-term affair with the poet Diane Di Prima, which produced another daughter. Hettie would pick up artists at the Cedar Tavern for revenge.

By the early 1960’s, LeRoi’s career would become more closely linked with radical Black politics. His controversial play “Dutchman,” first performed in March 1964, about a white woman killing a young Black man on the subway, was an off-Broadway hit and thrust LeRoi into the radical limelight. These racial politics of the 1960’s would eventually rip their marriage apart. Leroi had left Hettie by 1965 and became immersed in the Black Arts Movement. He later changed his name to Amiri Baraka.

In her memoir, Hettie Jones succeeds in pulling out the story of a doomed love affair and marriage and making it the story of the lost intellectual bohemia of Greenwich Village, where young people striving to become writers, poets and painters threw off the family histories and became part of a tight circle of other writers and intellectuals. People lived for their art, had sex with inappropriate people and had abortions, did speed, reefer and sometimes heroin, and become published writers.

Hettie wrote of a community of writers and painters who read each others’ books and promoted each other. It was a passionate period where an article in Commentary could set off a fistfight at the White Horse Tavern.

By the time their marriage implodes, Hettie and LeRoi are living in the East Village. More interracial couples are moving in and the area is already being colonized by the early hippieshippies, the next phase of the counterculture.

In 1958 when Hettie and LeRoi got together, by Hettie’s accounting, there seemed to be only three or four other interracial couples in the Village. When walking down the street together, the Italian residents would catcall the couple. Hettie wanted to confront them. Le Roi urged caution.

LeRoi’s family in Newark welcomed Hettie. On her side, Hettie kept here romance with LeRoi secret from her parents in Queens.

Hettie and Leroi started drinking at the famed San Remo Café on MacDougal and Bleecker, which was frequented by the Beats, which were at the height of the newfound fame, with the publication of Jack Kerouac’s On The Road. LeRoi wrote a fan letter to the poet Allen Ginsberg on toilet paper. Ginsberg, who was living in Paris, was impressed and wrote back with his own toilet paper letter. Ginsberg would become an introduction to the Village poetry scene for the young couple. In addition, they met the poet Frank O’Hara, and hung out with him at the Cedar Tavern, the 8th Street bar frequented by the Abstract Expressionist painters like Bill de Kooning and Franz Kline.

Hettie got a job at the Partisan Review, the influential political magazine ran by William Barrett. When the right-wing pundit Norman Podhertz attacked the Beats in his essay “The Know-Nothing Bohemians.” LeRoi responded with his own Beat defense in the Partisan Review.

In addition to the San Remo and the Cedar, there was The Five Spot on Cooper Square, where the Termini brothers took over their father’s workingman’s bar and rolled a piano inside. The bar quickly became one of the Village’s best jazz clubs, where David Amram, Ornette Coleman and even Billie Holiday would play.

The first time she got pregnant, Hettie had to travel to Pennsylvania, where a sympathetic doctor performed an illegal abortion. It was too dangerous for LeRoi to travel with her.

The second time Hettie became pregnant, she and LeRoi married at City Hall. Her father got wind of the pregnancy and confronts her, begging to allow him to annul the marriage and to get her another abortion. That was the end of Hettie’s relationship with her father.

The specter of violence always was present in LeRoi Jones’ life in the Village and in surrounding neighborhoods. While moving furniture to their new Chelsea apartment, LeRoi is savagely beaten by a white gang.

Hettie and LeRoi’s Chelsea apartment became the scene of great bohemian parties. Hettie learned how to make spaghetti for 30 for the large folding and stapling parties, where they’d compile copies of Yugen, their poetry magazine, that published the poetry of New York School of Poets like Frank O’Hara and John Ashbery, the Beats like Ginsberg and William Burroughs, and the Black Mountain poets like Robert Creeley.

In 2009, I interviewed Bill Manville, who wrote a bars column for the Voice in the late 1950s. He was the Jonses’ upstairs neighbor in 1958. “They’d invite me to the parties, but they were stoner parties,” said Manville. “I preferred my parties loud.”

When Jack Kerouac gave his famous reading at the Seven Arts Bookstore, afterwards the audience from the reading packed the apartment. When a drunk Kerouac heard that Hettie was pregnant, he embraced the couple and picked them both up off the ground.

Hettie wrote of using dexies, or speed, to finish putting out Yugen. Their parties were wild, with Allen Ginsberg and his boyfriend Peter Orlovsky stopping by and taking off their clothes.

Their daughter Kellie was born in 1959. The black-Jewish couple and their biracial baby drew stares on the street. When Hettie and the toddler Kellie were once taking the bus to Newark to see Grandma, a heavily made-up old woman was given them the evil eye. The euphoric toddler asked, “Mama, why is that woman ORANGE?”

In addition to publishing Yugen, the couple also printed poetry chapbooks with their Totem Press. One of the first books they published in 1958 was “This Kind of Bird Flies Backwards,” by the hipster poet Diane di Prima, a single mother by choice and upfront about her bisexuality.

LeRoi’s serial adultery started about two years into the marriage. Hettie noted that LeRoi’s sophistication, wit and kindness made him irressistable to white women in the Village who wanted to sleep with a Black man.

LeRoi started a long affair with di Prima, who had escaped her abusive, parochial childhood in Brooklyn for the freedom of the Village. She nude modeled, wrote poems and ran her own small printing press. At the Cedar one night, she noticed the despair on LeRoi’s face under the charming demeanor. Their affair went on for several years. They were even photographed together at the Cedar by the Village Voice photographer Fred McDarrah.

Hettie’s reaction to the affair was swift. She went to the Cedar and picked up a curly-headed painter she knew. She later settled into an affair with the soulful painter Mike Kanematsu, who had spent time in the World War II concentration camps for Japanese Americans, as well as fighting in the US Army in Europe.

Despite his own prolific affairs, LeRoi was apoplectic and confronted the lovers at Kanematsu’s home. Back at their home, LeRoi broke all the crockery and smacked Hettie. Locked in a fierce embrace and glaring at each other, the event signaled the beginning of the long, downward spiral of their marriage. Hettie wryly noted, they were both 25.

LeRoi’s literary career continued exploding. He wrote the cultural classic Blues People, which chronicled the rise of African-American music, from the blues created by enslaved people in the South to the evolution of jazz in New Orleans. LeRoi and Diane di Prima also started publishing “The Floating Bear,” a poetry newsletter. Articles in the newsletter resulted in Hettie and LeRoi’s apartment being raided by the FBI on obscenity charges.[144]. Meanwhile, Hettie and Roi had their second daughter Lisa in 1961. At the same time, Diane di Prima had her own Roi baby and moved two doors down from the Joneses. The two mothers would occasionally bump into each other on the street, pushing prams with their daughters.

Hettie was angry over Roi’s long-term affair with di Prima. She worked behind the scenes to make sure that di Prima was cut out of a major poetry anthology in the mid-1960’s.

In her own memoir Recollections of My Life as a Woman, Diane di Prima wrote that not all her activities with LeRoi were literary or sexual. Some were revolutionary. Di Prima recounted dressing very conservatively in a fake Chanel dres so she would not attract attention. She bought a box of grenade shells at an Army/Navy surplus store on 42nd Street, then delivered the shells to an activist friend of LeRoi’s in the Village. She did not ask questions. [DiPrima, p242]

Hettie’s memoir came out in 1990 and won critical acclaim for its clear-eyed look at the sexual and racial politics in Greenwich Village in the late 1950’s, early 1960’s, as told through a tumultuous romance and the blossoming and death of a marriage. There were great images of the lost bohemia of the Village, where Hettie and her friends would buy indestructible black tights from a dance supply store for the hipster women’s uniform. Strapped for cash all the time, Hettie and LeRoi would split the dollar salad at the San Remo.

When I first read the memoir in 2005, I was appalled that LeRoi left his wife and children in 1965 and betrayed the white poets like Frank O’Hara, who had mentored him and promoted LeRoi’s career. When questioned in the mid-1960s why he had turned on his poet friends like O’Hara, LeRoi told a black artist that “I was pissing in their beer.”

[Joe LeSueur, Frank’s roommate for a decade, got revenge on LeRoi years later in his posthumous memoir, Digressions on Some Poems by Frank O’Hara, published in 2001. He noted that LeRoi often spent the night at the O’Hara-LeSueur apartment, and that the lady-chaser LeRoi had an ongoing sexual relationship with O’Hara. In his own biography, City Poet by Brad Gooch, O’Hara said he believed LeRoi Jones was gay.]

Rereading the book again in 2021, I realized that the choices that LeRoi Jones faced were impossible. As his stature rose and his writing and speeches became more radical, Black activists began to attack him as speaking black, but marrying white, referring to Hettie. In 1964, after LeRoi wrote the play “Dutchman,” the play became an off-Broadway hit. When “Dutchman” was staged at Howard University, LeRoi’s alma mater, he refused to take Hettie with him to the opening night.

Though LeRoi had moved out, he would still come by the apartment to change clothes. The couple would make mournful love together. LeRoi took on a younger lover attached to the Black Power movement. He became friends and was a confidant with Malcolm X.

After her second daughter was born, Hettie’s father found out that Hettie’s mother was still in touch with her and would visit her grandchildren. The father gave Hettie an angry call, saying there would be no more contact, no letters, no visits from her mother. Hettie mused in her memoir that she had lost the men in her life during the same period, first her father, and now her seven-year love affair with LeRoi was ending.

In 1965, Malcolm X was assassinated. LeRoi and Hettie were at an event at the 8th Street Bookshop when they got the news. Again, Voice photographer Fred McDarrah took an important historical picture, the last public record of the estranged spouses together. When word filtered into the event that Malcolm was dead, LeRoi hurriedly left the event with several members of his new radical Black entourage.

LeRoi Jones soon moved with his Black girlfriend to Harlem and was one of the major founders of the Black Arts Movement. He changed his name to Amiri Baraka and started a Black theater company. Eventually, he moved back to Newark and married an African-American woman and had more children, including Ras Baraka, the present mayor of Newark.

Amiri Baraka’s career spanned 50 more years and 40 books. For many years, he taught at SUNY Stonybrook. He also continued his work in radical politics, and was arrested for gun possession and severely beaten by the police during the Newark Riots in July 1967. His reputation as a poet was marred by allegations of misogyny and homophobia. In the aftermath of September 11th, Amiri was appointed the poet laureate of New Jersey. In 2002, he read an anti-Semitic poem called “Who Blew Up America,” claiming that 4,000 Israeli citizens had been warned not to go to work at the World Trade Center on the day of the terror attack. The governor of New Jersey dissolved the poet laureate position to force Baraka out of office. Baraka died in New Jersey in 2014.

Hettie Jones stayed in the apartment on Cooper Square and raised her young daughters. Hettie became a noted editor and children’s book author. In 1998, she became an award-winning poet.

The kids all did very well. Kellie Jones has become one of the most famous curators and academics studying African-American art and has an endowed professorship at Columbia University. She is also the recipient of the prestigious “MacArthur genius grant.”

Lisa Jones went to Yale and wrote the “Skin Trade” column for the Village Voice for 15 years, the last period when it was a cool paper. [The Voice folded in 2018.] She had a cult following for her writings on culture and race at the Voice and is the author of the essay collection, Bulletproof Diva. She is also known as a playwright.

Dominique di Prima, the daughter of Diane di Prima and LeRoi Jones, is a well-known Los Angeles newscaster and TV personality.