(Denise Lassaw)

Denise Lassaw was born in New York City in 1945. She is the daughter of the prominent Abstract Expressionist sculptor Ibram Lassaw and was raised in an illegal artist’s loft on 6thAvenue. The social life with her father and mother Ernestine consisted of parties with painters like Saul Steinberg, Franz Kline, Larry Rivers and Elaine and Willem de Kooning. The de Koonings were her godparents, and once during a summer out in the Hamptons, she was bit by Jackson Pollock’s dog, because he hated her bicycle.

Denise Lassaw was present when artists like her father and the de Koonings were experiencing intense poverty while pursuing their art. She was a teenager when prosperity hit the Abstract Expressionists and the New York School. Some painters who had sold very little for decades and were suddenly selling their artwork, renting bigger studios and buying houses in Long Island villages like Springs, then a working-class community of potato farmers and fishermen.

After high school, Lassaw went to Paris to study art, but wound up living on a houseboat in the Seine, becoming the mistress of a Franco-Cuban painter. She made money drawing chalk paintings on the Paris sidewalks.

In the mid-1960’s, Lassaw followed her parents to Berkeley, California, where her father had a job teaching sculpture at UC Berkeley. When her family moved back to New York, Lassaw stayed and moved to San Francisco, just in time for the growing hippie scene in the Haight-Ashbury. Lassaw supported herself by welding belt buckles and brass buttons.

At 21, Lassaw was at the famed Human Be-In in San Francisco in January 1967, which was the first major public event of the hippie revolution that received national attention. Many people at the concert were on LSD, dancing to the Grateful Dead and Jefferson Airplane. During the Summer of Love, as the streets became packed with runaways and hippie wannabes, Lassaw left San Francisco and helped start one of the first communes in New Mexico.

Eventually, Lassaw moved to rural Alaska. In the mid-1970’s, she worked as a laborer and welder on the Trans-Alaskan Pipeline. She was also heavily engaged in the Anchorage arts community. She married a poet from Tibet and they founded Khawachen Dharma Center. Lassaw was involved in the production of two films on Tibet, including “Tibet: A Moment in Time.”

Since 2013, Lassaw and her partner Serge Lecomte, a painter and linguist, have lived in Bellingham, Washington. Lassaw is actively working on a massive catalog raisonné of the sculptures of her father Ibram Lassaw.

I spoke with Denise Lassaw, who is now 78, at her home by telephone in Washington State, in November 2023.

DYLAN FOLEY: Denise Lassaw, what day is today? November 3rd, 2023. Good morning. How are you doing today?

DENISE LASSAW: I'm doing okay. I'm hiding out in my little studio/work room because we're getting our kitchen floor redone. The floor is old, from 1990, and it's all cracked up. The contractor said, "Well, we got the materials and we had a cancellation. Can we come tomorrow?” So the house is in chaos.

I've done construction work on my own houses, and I also worked on the Trans-Alaska Pipeline as a laborer. I'm pretty familiar with construction.

DF: What year were you working on the Trans-Alaskan Pipeline?

DL: 1976. I only worked on the Trans-Alaskan pipeline for about five months. It sounds sexy but infers something more than the truth. I was in the Laborers’ Union for several years and worked on construction projects in and around Anchorage.

DF: 1976? You were already out of school? Did you leave New York when you went to college?

DL: No, I didn't. I didn't do, you know, what’s the usual way that people do things-- you get born, you go to school, you go to high school, you graduate, you go to college. You get a job, you get married, you retire and you die. I didn't follow that route at all.

I was born in 1945. I went to the old PS 41. It's now on 11th Street between Sixth Avenue and Seventh Avenue.

DF: Where did you say the old school was?

DL: The old PS 41 was on Greenwich Avenue between 10th and 11th Streets. One of your (advance) questions was about the Women's House of Detention. I grew up on 12th Street and Sixth Avenue. I walked by myself to elementary school, to PS 41. And every day, at least twice a day, I'd pass the Women's House of Detention. And I remember people in the streets yelling up to their sweeties in the prison.

You know, the library next door, that was once the courthouse?

DF: I know it very well, what is now the Jefferson Market Library.

DL: When I was growing up, our loft had south-facing windows that looked out at the clock tower. And that's how we told time. We didn't need to own a clock. I always had a fantasy of living in the clock tower.

Back sometime in the nineties, I don't remember what year it was, every time I went to New York, I would try to do something different. So one time I just walked into the library and I told 'em how I'd grown up with looking at the clock tower, and I really wanted to go to it. And they said, well, you're not gonna jump to commit suicide, are you? I said, no, <laugh>. So anyway, they got the janitor.

And I told 'em I'd worked construction, and I'd climbed many straight up and down, you know, metal ladders, I wasn't afraid of heights or anything. And the two of us went up to the clock tower. I actually got to walk around that balcony. I took a few pictures, then I ran out of film, and I went inside the clock, and it was really cool.

DF: Did you leave town for college? Or did you just leave town?

DL: I went to the High School of Music and Art. I was there for three years, but I was a sophomore twice. I had all my wonderful art classes, but somehow I didn't believe in any of the other stuff. I practiced invisibility in algebra class, and it really worked, but I guess it didn’t work because I failed. I had a geography teacher. She was grumpy and I hated her. And I failed her class twice.

Then in 1962, ‘63, my father was a resident artist at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina. I finished high school there. Because I didn't know anybody, there was no Greenwich Village, and there was nothing to do. I actually studied and they didn't care about math. And I took three English classes together and I loved it. And anyway, I graduated.

And then I went to Paris. I was supposed to be going to art school, a place called the Academy De Feu, which could be fire or it could be madhouse.

Paris was far too interesting for me to actually do anything cool at the school. It was the kind of place where you had to be very motivated by yourself. It wasn't like there were classes where they said, okay, today we're gonna do a head in clay or something. I ended up living on a little boat in the Seine. I was a mistress to a French-Cuban painter. And this boat was about, I don't know, less than 30-feet long. It had no motor and no sail. It was a sailboat, but it didn't have a sail. And I lived with, Armand Campi, his Dutch wife and two little children <laugh>.

DF: You were also romantically involved with him as well?

DL: Yeah, yeah. I was, we used to go to the Cafe Coupole, with Armand, who was quite short, and Elsie was about six feet tall. I'm not very tall. But anyway, Armand would have us one on each arm, and he would introduce us as “My wife Elsie, and my mistress, Denise. Anyway, that was amusing for a while. Armand and I used to make drawings in the street with colored chalk. I didn't actually make "a living"- rather we prevented starvation by drawing and sometimes made as much as 10 dollars a day- but we didn't work in the rain or when something else was more interesting to do. And then my father used to send me a hundred dollars a month, which I could actually live on.

I was in France, and then in other parts of Europe for close to a year. I came back to New York. Our original studio was torn down in 1960. My father got this other studio on the corner of 12th Street and Greenwich Street. And that was a wonderful studio, too. It had ships portholes. Later on, when lofts became legal, they threw my father out. They said he had made it already, and he didn't deserve a loft.

DF: Who threw him out, the landlord or the city?

DL: The tenants’ association. Anyway, I was in California by that time.

In 1965, I was in New York. I had this boyfriend, and then he ran off with my best friend, Nancy. They went to Provincetown. I was a little bit depressed, but actually it was a very, very good thing. I'm so glad that he left. Then my father had been invited to teach at UC Berkeley.

And I decided at first in the summer to go to Colorado. He was teaching at Colorado Springs at an art school. I jumped on the train with my oxyacetylene equipment and, you know, a few pair of underwear. And I went out to Colorado Springs and spent the summer there. Then we went to California. On the way, we went to Yellowstone and then visited David Hare, the sculptor, who had a ranch in Wyoming. We visited there for about a week. And anyway, California in ‘65, that was the beginning of the free speech movement and LSD. It was quite an exciting place.

There was a fountain on campus that we called Ludwig's Fountain. Ludwig was a dog who spent most of his days there. He was a poodle-type dog. He spent most of his days in the fountain, and people would throw balls for him. It was his fountain. I hung out, you know, at the fountain. I was sort of an unofficial assistant in the welding class. And then I could take any art class I wanted because all of our friends were teaching there. William King, you know, he was teaching and what's his name? It's Peter Volkis, who was at Berkeley. So I could go to any art class I wanted. And then I also went to the library. And because of my father, I could go to the rare book room and I could sit in there and look at things.

So anyway, in the spring of ‘66, my parents were packing up to go back to New York, and they said, are you coming back to New York? And I said, “Bye.” And I ended up moving over to the Haight-Ashbury.

DF: Wow, right in time for the beginning of the hippies.

DL: Oh, yeah. Over the winter I had attended all the dances in SF. The Acid Test was a big one, so I had some idea of what was going on and I knew a few people. I made belt buckles and bronze buttons and necklaces and things, welded stuff, which I sold. And I also modeled for art classes. And my father sent me a hundred bucks a month <laugh>. My rent was $33, and food was very cheap. Cheap. And I really never had much interest in money anyway. So as long as I wasn't starving to death or out on the street, I was okay. In fact, if I had $5 in my pocket, I felt absolutely wealthy.

DF: I've been doing a lot of research on the hippies in the East Village, in 1967. I've been studying Emmett Grogan and the Diggers.

DL: Oh yeah, sure. I remember him. Yeah, they used to give us free food in Panhandle Park.

By early spring of ‘67, I left. The Haight was absolutely this fantastic time. And, you know, people used to give you LSD and I was never too much into smoking pot, but I smoked sometimes. It's a wonderful community, but then, you know, it gets popular. Then you have all these wannabe hippies. And everything is sex, drugs, and rock and roll. And it was different because of this. This is sort of similar to what happened to the New York artists in the 1950’s. you know?

When everybody was poor, and they were committed to their creative work and to all kinds of ideas. And they used to argue over philosophies and art history and all of that. And the money wasn't part of it because nobody had any.

But as soon as some people began getting money, there were the jealousies, you know. The same thing happened in Haight-Ashbury. There were some people who were having stores and mostly their stores were very nice then all these new people came, and they didn't have any of the background in the philosophy of what was going on. To them, it was just like, okay, I don't have to have any responsibility for anything, and I can get high all day. And it really wasn't about that.

DF: Where did you go after the Haight?

DL: Well, I had this boyfriend. I had a few…I had one boyfriend who said, “You're really a country girl, you should live in the country.” And I said, nah, I, you know, I like the city. I really like San Francisco. And then I had this other boyfriend who was a big influence on my life. And when we met at the I Thou Cafe on Haight Street. It was kind of a Gurdjieff-influenced place.

And he thought I was the little match girl. And I thought he was a mechanic from Texas, which turned out to be fairly true <laugh>, but he was more than that. Anyway, the first thing he said to me was, “when we go to New York together..,” and I thought, wait, this guy's crazy. But then a few months later, he says, so are you coming to New York? And I said, no. I mean, I didn't wanna be in New York. And, uh, then he was in New York, and a few months later, so I hitchhiked to New York with this other guy, and my dog. And my mechanic from Texas, a guy who was also an artist and a poet, and a very psychic person. He was already involved with several other women. I left him and I went to Colorado, and I visited friends in Boulder. And this friend of mine in New York was pregnant, and she needed to get out of New York. Her boyfriend wasn't gonna marry her. We hitchhiked together. That's getting ahead of the story. We went to Drop City, which was one of the first communes. And this was in Trinidad, Colorado.

DF: I've never heard of Drop City.

DL: Yeah. They made domes. They made 'em out of the tops of cars. They took the metal pieces, they chopped it out with an ax, and they, they made, they, they called 'em Zomes. Or maybe that was later. Steve Durkey called 'em Zomes. Anyway, they made these domes out of metal car tops, and they were having this love festival. And so we went to that. And there I ran into the poet Max Finstein, who used to be a New York poet. And he's actually an old beatnik. [I met] a guy named Rick Klein, who was from Philadelphia or Baltimore. And they said that they were starting a commune outside of Taos. And I loved Taos. I had been there in 1954 when I was eight years old. We spent the summer there.

And so anyway, I hitchhiked with my friend Cora, to California, and she had to see somebody in San Francisco, and I had to pick up some welding rods. And then, let's see… We ended up at the Monterey Pops Festival. I had, you know, all kinds of little adventures. Then I hitchhiked by myself with my dog back to New Mexico. And so I was there at the beginning of a community called New Buffalo. We lived in teepees, and we were growing our own veggies and had some goats and, and building a big adobe communal house. That was all in ‘67. And then by ‘68, we were being inundated by all these people who were on the road, and they would just come and expect to be fed. You're supposed to love everybody. They just wanted to be taken care of, and most of them weren't too great, you know, and we had this family meeting, and I said, well, wouldn't it be more loving to tell them, look, we need to have food, and, and we're working. We're trying to build this house. If you wanna stay here, help us, you know, contribute your energies and labors to making this place happen. Otherwise, you should leave. I thought that maybe they would wake up and say, “Oh, okay. You know, it's an exchange of energy.” But one of the macho guys said, “You can leave, too,” which was another great thing. So I left and I moved across the valley. I lived in a tent somewhere, with some other people. And then I moved down to a place called Canoncito, closer to Espanola. And anyway, in the spring of ‘69… there's just too many thousands of stories…I had a VW bus and I drove to Alaska, just to see what it looked like.

DF: By yourself?

DL: Well, I started out with these three guys. We got to Sausalito and they got all high on drugs and drinking, and they just weren't really great people.

I went up to Northern California where this guy lived, who had been my father's official assistant at Berkeley. I made some belt buckles and stuff to sell, to make money. I sent them to New York for my mother to sell. And then I met another guy and told him that I had been on my way to Alaska, but I wasn't gonna go. And he said, “Wow, Alaska.” Oh, okay. And so the next thing you know, we're on our way to Alaska. And long story, a zillion stories. I ended up staying for 44 years.

DF: So moving to Washington State was a new development?

DL: We, my partner and I, moved down here in 2013.

DF: What town or city were you in, in Alaska?

DL: I spent about five years living out in the woods. Two years by myself. And then I married an enchanted bear. Then the pipeline came along and I got a job as a laborer.

And I escaped from the bear. And I went to Hawaii to eat magic mushrooms and swim. And then I went to New York, and then back to Alaska. And then I ended up in Anchorage. I was part of the Visual Arts Center there. And that was really nice.

DF: When you say an enchanted bear, what does that mean?

DL: It was a guy, okay. The reason I say an enchanted bear, you know, Prince Charming…when you kiss the prince. In “Beauty and the Beast,” Beauty goes to the Beast’s house. And he is repulsive, but she kisses him eventually, and that breaks a spell, and he turns into a very handsome and lovely prince.

But when you start out, if the one being enchanted is not a prince who turns into a beast, but a beast who begins to look like a prince. When you kiss him, he turns back into a beast? <laugh>. So I had to escape from him.

I had a lot of very interesting adventures there, but not that I would actually like to repeat. I mean, I did it and I learned something, and it's gone. So then I was in Anchorage. I was living in a Quonset hut in Anchorage, and being part of the Visual Arts Center. I decided to take industrial welding at the Community College, because on the pipeline, the welders on the pipeline were making $18 an hour. And as a laborer, I was making $13, which in 1976, ‘77 was pretty good money.

I was taking an industrial welding class, and that was a 12-credit class. And at the time, if you took 12 credits, you could take as many more as you wanted for free. I signed up for ceramics, because I love playing with clay. They made me the lab assistant for clay. I would mix clay bodies and glazes, and fire the kilns. And it was heaven. Absolutely heaven.

Then I took a class in the anthropology of Soviet Central Asia. It was a graduate-level class, but I didn't care. And it only had five people, and then they dropped out one by one, and there was only me and one old lady taking it. And so I got an A<laugh>.

DF: Can we go back to New York?

DL: Yeah, sure. We can go back to New York.

DF: These stories, the hippie stuff from the Haight that you just told me is amazing, though. Were you there at the Human Be-In in January 1967 in the Haight?

DL: I was there. I was at the Be-In.

DF: I think it estimates that there were 50,000 to 75,000 kids came into San Francisco during the Summer of Love.

DL: Yeah, it changed the whole complexity of the neighborhood.

DL: Bad stuff was happening at the same time because people were preying on the kids, you know, and then also the hygiene issues and the lost children.

DL: When you took LSD or psilocybin, peyote or something, you had to have the right kind of mind. If you were completely unprepared and you started to see things, like hallucinating colors or people turning into monsters or some kind of thing like that. It's all from your own brain. Whatever is in your head is manifested in your vision. If you have a little bit of Zen training or some philosophy and whatever, then you don't have all that crap. And these days anyway, you don't know what you're getting.

We had Owsley, who was making acid, and the first acid I took was Sandoz. So it was very, very pure. I never had any bad acid.

[EDITOR’S NOTE: Owsley Stanley was the legendary San Francisco chemist, who produced pure LSD for Ken Kesey and the Merry Pranksters in the 1960’s, as well as acid for the Beatles. He later became the Grateful Dead’s sound engineer. He spent time in federal prison in the late 1960s and early 1970s for drug possession.]

DL: Anyway, going back to New York. San Francisco was my hippie days <laugh>. I write about those too, but we'll go back a couple of decades here.

DF: Was your mother friends with Elaine in Brooklyn? Did they grow up together?

DL: No, Elaine grew up in Brooklyn. My mother was born in Shreveport, Louisiana. There was an artist down there named Arthur Morgan. You know the heads of the presidents in South Dakota?

DF Yes, Mt. Rushmore.

DL: What's his name? Borland or something? Arthur Morgan had helped him. And he lived in Shreveport, and his wife Gladys taught art at the college. My mother was going to the college in Shreveport. She took classes with Arthur Morgan, too. And one of his other students said, “Oh, every year she went to New York and she went to the Art Students League. She told my mother, absolutely, she had to go to study with Kunioshi So my mother convinced her father. I think this was in 1932. She had graduated from college, and her father gave her some money, and she had some sort of relatives in New York. And he said, when the money runs out, you have to come home.

My mother stayed with those relatives a little bit, but she didn't like it very much. She went and got herself, her own apartment, and she got a job 'cause she knew the money wouldn't last. Mm-Hmm.

She studied with Kunioshi and then she also went to the, what was it called? The American Artists School. I think it was on 14th Street. And Elaine was going there. And Elaine and Milton Resnick were a couple.

Elaine was living at home. She was only 18 years old, and my mother was just a little bit older. My mother was born in 1913, and Elaine in 1918. They became very good buddies.

And then Elaine wanted a place where she and Milton could get together, although she was still officially living at home. So Ernestine rented a loft, and she was the only one who had a job. Milton Resnick was selling blood to have money. They became, you know, the best buddies. And they used to run around New York together and get into all kinds of mischief. They were very naughty. I love the naughty stories from my parents’ youth.

Elaine knew Max Spivak and she didn't like him. One time they were running around town and she said, oh, you see that building over there? There's this guy who lives there. I don't like him. Let's go ring his doorbell and make him come downstairs to open the door and we'll hide. And it just so happened that my father was living in the back half of that studio with Max and Max wasn't there. It was my father who came down the stairs and looked around. He opened the door, he looked around. There was nobody there. Elaine and Ernestine were going, “Hee, hee, hee” <laugh>. My mother didn't meet him then, just saw him.

They used to pee behind parked cars if they were out, running around and they had to pee, you know, <laugh>. They were very unconventional.

And then Elaine met Bill. They got together, and she dropped Milton. And Milton was devastated.

DF: When did your mother meet your father?

DL: She had a job at Famous Funnies, which was one of the first outfits that actually printed comic books. And she was a coloring editor. She actually worked there for about 10 years, past the time that I was born.

My mother was gonna take a vacation, and every time she had a vacation, she went back to Louisiana. And her girlfriend said, why are you gonna go there? Why don't you go to Provincetown, do something different? My mother called the Chamber of Commerce in Provincetown, and they told her about a place to get a room. She went to Provincetown. My father was working for Norman Belle Geddes. This is 1944.

Ibram was making relief maps for the Army. And he got to take a vacation. He went to Provincetown. There was a place like a drug store that made breakfast And so Ibram went to the Drug Store cafe, and there were a couple of friends of his from New York having breakfast. And there was this girl sitting with them, and she was Ernestine. They met, and then spent a few days running around the dunes together. Ernestine had to go back to the city to her job. And then Ibram came back to the city and they started living together. They were married in December of ‘44. And I was born in December of ‘45.

They moved. He had a little place on Cornelia Street, and she had a place on 22nd Street. They found the loft on 12th Street. And they moved in there together.

DF: What was the loft space like?

DL: I'm not sure exactly how wide it was. It was over 20 feet wide. Maybe 60 feet long. It was a very nice space. And nothing had happened in there for thousands of years. We had three windows that faced east on Sixth Avenue. We had, I don't know, maybe seven windows that face south. And then we had a fire escape, and we had two skylights. And the fire escape was on the north side. We had a couple of windows to the north, as well as two skylights. You know it was completely illegal to live in industrial lofts in those days. We were always scared of the landlord or fire inspectors.

DF: Was your father able to weld in the building?

DL: He didn't start welding until 1951 because he never had money to buy the equipment he needed. He learned to weld in the army.

So then in 1951, after, you know, being a sculptor for 20 years, he sold his first sculpture, and with that money, he bought the oxyacetylene equipment.

DF: What year was “12 Americans,” where Ibram Lassaw’s work was featured?

DL: I don't know, maybe 1956.

DF: Did your parents divide up the space or was it pretty open?

DL: Half of it was the studio and half of it was our living area. And what became my room had been an elevator shaft where somebody put in a floor. The loft still had these wonderful beams, big chunky wooden beams. This building was from 1888.

And it had big columns down the middle to hold up the ceiling. My father did all the plumbing and the electric. He ran a gas line for cooking <laugh>. But we didn't have gas at first, we just had a kerosene stove, which he vented out the window. And that was the only heat, except in the studio, he had a potbelly stove. We used to scrounge wood on the street to burn for heat.

When I was little, going to elementary school, it would be cold. And, you know, my mother would heat up my clothes on the kerosene stove, and then she'd call me and I'd run to the stove and jump into my nice warm clothes. So it was really nice. It was like being in the country in the middle of the city.

DF: What kind of building was it?

DL: It was a brick building. On the inside, it was entirely wood. The staircases were wood, the floors, the ceiling. And of course, the walls were plaster.

DF: Were you an only child?

DL: I was the only child.

DF: What was the social dynamic? Did your family wind up hanging out with other artists and their children? Or did you hang out with civilians?

DL: Well, we didn't have any relatives. My mother had two brothers and a sister, but they were in the south. You know, maybe we saw them once a year or something, and my southern grandparents once a year. My father had lost everybody. His father died in 1940 in an accident. And his sister died of TB in 1946. And then his mother died in, I think, in ’53. I hardly remember her. He had a few cousins, but he didn't really like any of those people. He thought they were very boring 'cause they were business people.

DF: Did your father’s family leave Egypt for economic opportunity? Is the family Jewish?

DL: My grandfather, both my grandparents were born around Odessa. Yeah. My grandmother was born, I think in Theodosia, which is in the Crimea. At one point they were letting Jews in the czar’s military.

My grandfather had some military training, and in 1905, there were a couple of very horrible pogroms in Odessa. And my grandfather had his pistol left over from his military time. And when these rioters came to his house, he killed two policemen.

He had to get out of there, and his father, his elder brother and him took a ship. And I don't know how, I don't know what the route was. I don't know the timeline. I have letters from him in 1907. And his brother Max stayed in New York, and he became a businessman and had a store up on 125th Street.

My grandfather Philip, ended up in Hearn, Texas, working for some kind of a cousin of his. He had been trained as an accountant. So I don't know exactly what he was doing. You know, I always say he rode around on a horse for a couple of years, but he wrote letters back to Bertha, his beloved in Odessa. And around, I don't know, 1908 or something, he went back and then they got married, I think in 1912.

She had a sister who lived in Alexandria, Egypt. They wanted to go to New York. That was the idea, because Max was in New York, but they needed to make money. So first they got as far as Alexandria. My grandfather was working, but then Ibram was born in 1913, and his sister was born in 1917.

And then World War I happened, so they couldn't go anywhere. And by 1921, the war was over and travel was possible again. And that's when Max helped them. They got a ship from Alexandria to Constantinople, then to Malta, to Marseille. And they got a ship from Marseille to New York. My father was eight years old when he arrived.

DF: Did your father speak Russian or did he have any Yiddish?

DL: He spoke Russian at home, and he spoke French at school. He went to the French Lycee in Alexandria. As soon as he got here, he learned English. And he never had an accent of any kind. I never heard him speak Yiddish and my mother didn't know anything but English.

He was so young. He really liked New York. They lived in Brooklyn. And he used to wander all over Brooklyn. Back in Alexandria, he loved to play with clay. There was a big park, and there were some clay pits and he used to play with clay. In Brooklyn wandering around, he discovered the Brooklyn Children's Museum.

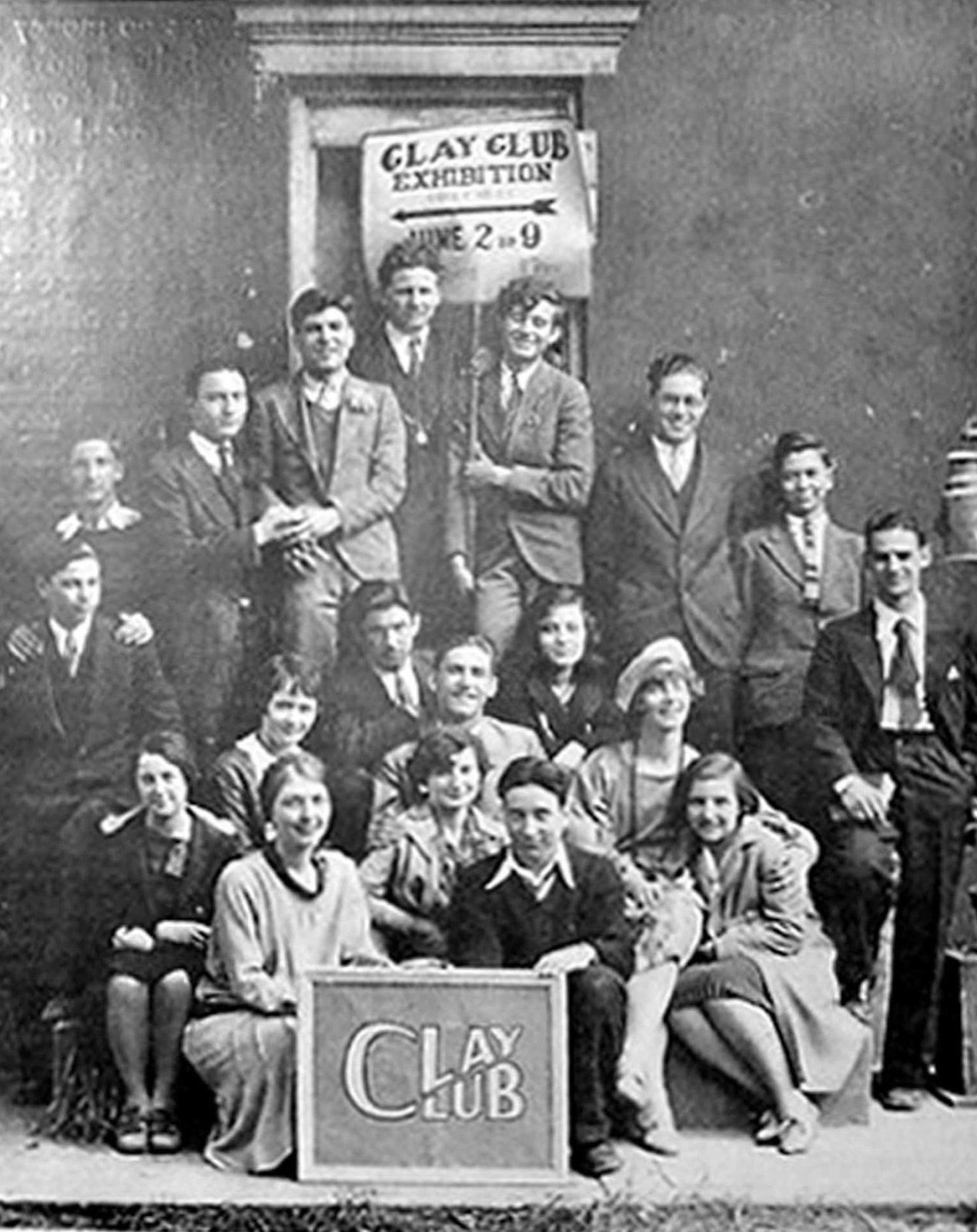

There were two things he signed up for. One was a clay class taught by a fantastic woman named Dorothea Denslow. And the other was a Nature Studies class, which was kind of like a Boy Scouts troup. And that was taught by Cornelius Denslow, her brother.

Somebody ought to do their dissertation on Dorothea, because the whole Denslow family was really quite incredible. They were an old American family. There were a lot of naturalists and painters and all kinds of interesting people in their background. And Dorothea and Cornelius's parents had started the Natural Method School. It was an alternative school. And I think that's what it was called. Dorothea was trained as a sculptor, but she could also look at a skeleton or scull and recreate the face, just doing it in clay or plaster.

Anyway, she was a very interesting young woman and very enthusiastic about sculpture. First Ibram was part of that clay class, and then later, with some of the senior students who wanted to study more, they rented this little coach house just right around the area of the museum and had classes there. Later they moved over to Eighth Street, to the building that the Whitney was in. It wasn't the Whitney yet. He was part of what's called the Clay Club. And a lot of very important people were at the Clay Club. Noguchi was there. Harry Holtzman was there. There were all kinds of people who got their start at that place. And then the Clay Club later morphed into the Sculpture Center. And it was uptown on 56th Street or something. And then it moved to Queens. And it's in Queens now. But it's a totally different place now because it started out as a place for sculptors to work on their sculptures. But now it's more of an exhibition space.

DF: How did your father wind up in the Works Progress Administration, jumping ahead a little?

DL: He moved over to the Village. He was hanging out and he was doing his work. He was desperately poor. And it was the Depression. And he was part of the Artists’ Union. They had demonstrations and everything. A lot of different trades were demonstrating. And so that was the beginning of a program, to help workers make a living. First it was the PWAP, then it became the WPA. One of his first jobs with that was cleaning pigeon shit off of statues in the parks.

DF: I think Jackson Pollock had the same job.

DL: Yeah. Jackson. And they worked together on that.

DF: Pollock’s wife, the painter Lee Krasner, was involved with the Artists’ Union. I think she was, in her youth, a Communist or was involved with the Communist Party.

DL: Yeah. A lot of those people were. My father wasn't.

I sent you a picture of Alice Mason.

DF: I don't know anything about her.

DL: Alice Mason was one of the first abstract artists. And my father and Alice and some other people started the American Abstract Artists Group.

So that was like 1936. And then in ‘37, they had their first exhibition because none of 'em could get a gallery. Yeah. There was absolutely no hope of selling anything or having anybody represent them. So they rented a space at the Squibb Gallery and they had this show, which I sent you a picture of. So that was in ‘37 when the show happened. And there are three plaster sculptures in that picture. And those are my father's abstract sculptures. He made his first completely abstract work in 1933.

But anyway, he met Alice Mason at the Washington Square Art Show. And, you know, he was wandering around. Of course there's the usual bunch of junk and then people who were very competent, but boring and lovely little watercolors of flowers and stuff like that. And here was this woman trying to sell pictures that were abstract.

And so anyway, they got together. She was married and had two kids, but her husband was a sea captain, and he would be away for six, eight months of the year. They kind of had an arrangement that they could have other partners. So Ibram and Alice were boyfriend-girlfriend. And she was one of the people who began the American Abstract Artists.

DF: I think Franz Kline was also at the Washington Square Art Show, like other struggling artists from the thirties.

The poverty was so intense, you know. Like, like when, when Elaine and Bill got together in the 1940’s, he built her a beautiful loft, and they got kicked out like six months later because they couldn't afford the $30 a month rent.

DL: Oh, yeah. And, and you know, Elaine's my godmother. Yeah. Elaine and Bill are my godparents. And she used to tell me stories about how broke they were. You know, if they got a dollar should we buy food or cigarettes or some more paint? And they would always buy the paint.

And Elaine was never a good cook. But my mother was an excellent cook, and she could make wonderful meals out of next to nothing. My mother was working, so she always had a little bit of money.

DF: Your mother was still at the Famous Funnies place for at least for the first decade of your life and their married life.

DL: You know, we always had dinner around five o'clock in the evening. So Elaine and Bill would always show up, <laugh> no questions asked. They would show up. Oh, okay. It's dinner time. Just put some more plates on the table. <laugh>.

DF: When you were really little, what was the social life like? Was it going to other people's lofts for a party or dinner parties?

DL: Mostly, yeah. We went to parties. And a big part of social life was Washington Square Park. Before my parents met, my father and other artist friends would meet in the park. And they would talk art history and argue about things. And when the weather was bad, they went to a cafeteria.

They got kicked out because they would get loud and there were too many people sitting around the table. And that's when the idea of having their own place came about. So that was the beginning of the Artists Club in 1949. I'm sitting right now at the table that the Club, the big organizing meeting of the Club, was held around. <laugh>. This table was ours, the organizing meeting was at our loft. I was there, but I could just look over the top of the table. I didn't take part.

DF: Did you ever come across Cynthia Navarrata?

DL: Yeah, sure. We knew Cynthia, because she was married to the artist Emmanuel Navaratta.

DF: An acquaintance of mine wrote a biography of Milton Resnick. And there's this horrible story that Cynthia was given all the tapes, there were audio tapes of all the lectures that took place at the club. And she was given all the tapes, and she was going hand them off to somebody to transfer them to the more modern technology. All the tapes were burned and destroyed.

DL: I would question that. In the beginning, I heard my parents talk about this a lot. The guys really didn't want publicity. They didn't have a feeling of, of being historical, you know? There may have come a time in the later stages of the club when somebody recorded things, but nobody knew about recording, how to record. No one would've had a reel-to-reel tape recorder. And I don't think they would've liked the idea. It would've been a real chore.

You would've needed microphones. And the way things worked at the Club is that, you know, if they had a panel, then there were people sitting around a table, but everybody else was sitting around. The audience participated as much as the people on the panel. It would've been hard to mic. Maybe in some of the later years of the Club, perhaps somebody did record things.

DF: The only surviving tape is there's a tape of Milton Resnick. I think he may be giving a lecture. I don't think it was a panel. It's in this biography of him, you know?

DL: Yeah. I have that book, too.

DF: The book is Out of the Picture. The writer is Geoffrey Dorfman. I met him several times. He's a painter and a pianist.

DL: I've met him.

DF: Yeah. But, It's not a great book, but it's interesting because there are some things in there that are only in that book, like about his war record. At the end of the war, Milton did some heroic things and also saw some horrible things at the same time.

DL: He probably had some, what is it called? PTSD. Which nobody knew about then. I mean, they knew about it, but they didn't have a formal name.

DF: When the poor people who came back from the war, they called it shellshock. The attitude was “Okay, you're back now. Get a job, get married, have kids.”

DL: Right.

DF: You're not going to have treatment for seeing the bodies at Auschwitz or surviving D-Day, you know, or all the horrible things that happened to the young men and some young women who went through the meat grinder of WWII.

With your mother having a basic job, was there more financial stability in your family than other artists?

DL: There were some artists who came from families who were wealthy.

So, you know, they didn't have much trouble.

But most of our friends were broke. Yeah. And there was a joke that they used to tell about the $10, like somebody would lend $10 to Bill and he would lend it to Milton. And Milton would lend it to somebody, who lent it to somebody who lent it to my father, who lent it back to Bill.

Everybody was broke, but they never said “poor.” They just didn't have money, but the life was so rich.

Most, all our friends lived in lofts, and all illegally, you know, which was exciting. And I thought, you know, I felt we were like being part of a tribe of gypsies. You have your own rules, your own codes of behavior, and it doesn't conform to the rest of the people around you. But who gives a shit?

DF: In the late 1950’s, when some Abstract Expressionists were able to sell their art and made money, some bought houses in Long Island villages like Springs.

DL: It didn't happen suddenly and not everyone made all that much money or could afford to buy houses or build them. Also, the houses they bought were mostly ordinary old houses which they fixed up. People think of "The Hamptons" and houses in the Hamptons and they think of huge, fancy things. None of our artist friends ever bought houses like that, except Ossorio but he came from a very wealthy family- it was not from selling art.

Also, artists mostly bought houses in Springs or Sag Harbor,or Montauk, which was another part of East Hampton where real people lived, the potato farmers, dairy farmers, carpenters, fisherman, plumbers etc., the descendants of the original settlers of Long Island. "The Hamptons" is where the wealthy people live. At the time - the early 50s– the Hamptons was not what it is now. Rich people, from old money lived in mansions near the ocean or in the town of East Hampton, but the scene was fairly quiet- being wealthy was not being a show-off as it is today. There were no fancy stores selling blue jeans for hundreds of dollars. "Brands" were not important. You could afford to buy groceries and taxes weren't much, you could park anywhere anytime or go to a restaurant without ever thinking of making a reservation. You could go to the beach not imagining a beach permit. The dunes were vast and quiet. No one prevented you from making bonfires and dancing nude in the night.

DF: I read multiple books at a time, but I've been reading the gigantic de Kooning biography. And your mother and father are quoted extensively in that one. I just did this intense reading of Mary Gabriel's Ninth Street Women.

DL: Ninth Street Women. That's a wonderful book.

DF: That is truly a wonderful book. But the thing is, Mary Gabriel did all these interviews in the early nineties. The book didn't come out ‘til something like 2016. She has all these voices of people who were dead.

DL: She got voices from real people. Well, Elaine was already dead. I mean, Elaine died in ‘89.

DF: Gabriel interviewed Helen Frankenthaler. Did you know her? Was she part of the social life?

DL: She was more of an uptown person. She married Clement Greenberg, and we hated him.

DF: I just read her biography, Fierce Poise. She was the daughter of a judge. She was German-Jewish aristocracy. She was Greenberg's girlfriend for five years until she finally started dating a better-looking, age-appropriate man.

DL: Greenberg was an asshole. Paul Jenkins was married to our friend Alice Baber. He invited my parents to come to a party at Greenberg's house, but Greenberg hadn't invited my parents. And when they got there, he wouldn't let them in.

DF: He does sound like he was a very angry man.

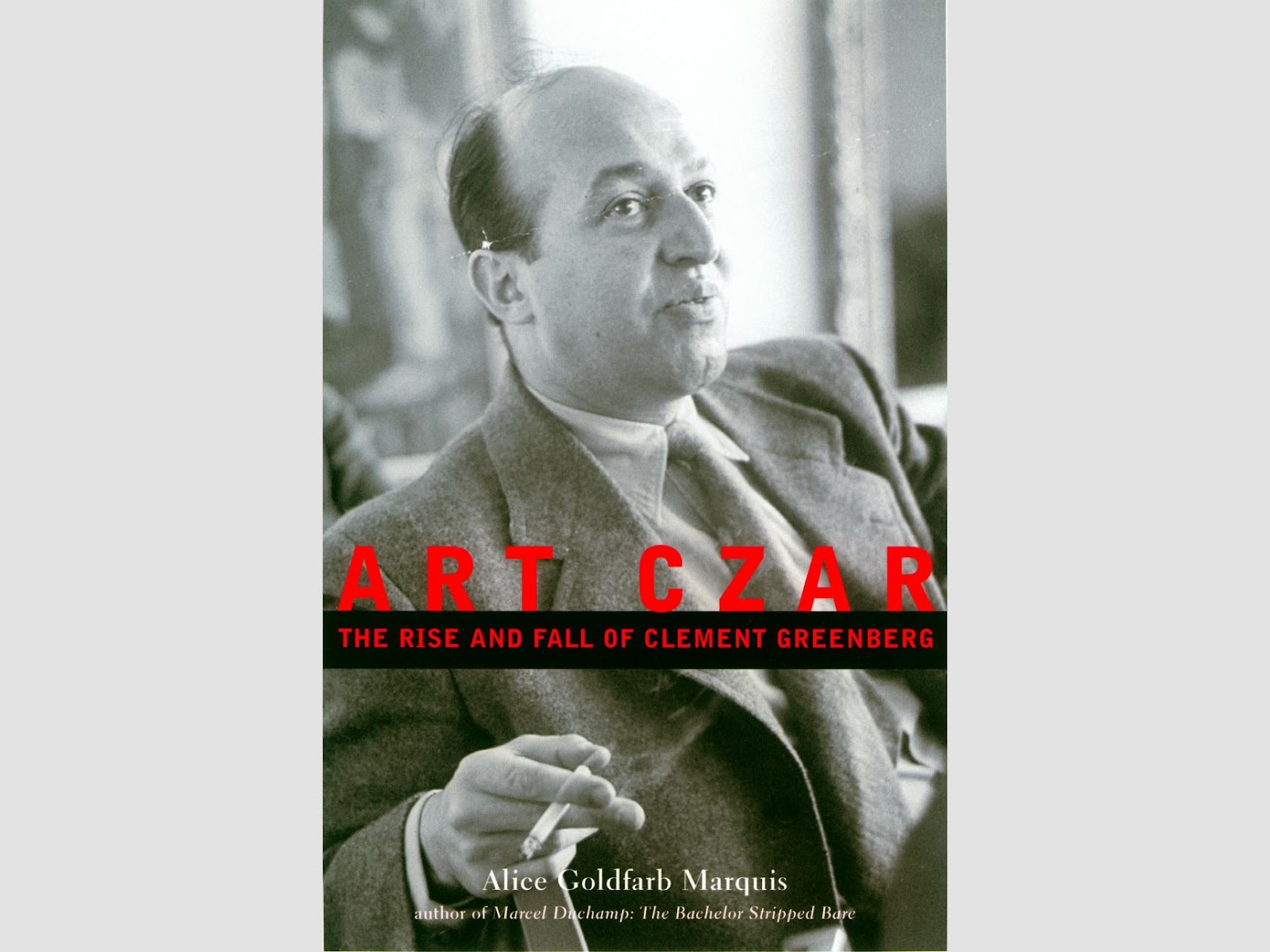

DL: Did you read the book called Art Czar?

DF: I haven't read it closely yet, but I did read a disturbing thing about him that he would go to studios and he would basically pick paintings he wanted, usually the best paintings. When he died, he died with millions of dollars’ worth of artwork that he had taken from painters.

There was also a very strange crossing of the lines of critics reviewing their friends, like Frank O’Hara, a fascinating character. Frank O'Hara was sleeping with Larry Rivers, but would also review him and sort of helped make Larry Rivers.

DL: Of course, Frank was sleeping with everybody else, too. And so was Larry. Did you read Larry's book?

DF: Yes, What Have I Done? I've read big chunks of it.

DL: I think it should be retitled, “What Haven't I Done?”

DF: Larry Rivers was a fascinating character. He sort of used his body like a credit card. He was a very handsome dude, you know, with that romantic, high cheekboned, big-nosed face. Just a beautiful man. I met him a year or two before he died for like 30 seconds.

DL: I posed for him.

DF: How old were you?

DL: When I was a teenager.

DF: Larry did that creepy thing. He did that movie about breasts where he would interview his wife and teen daughters.

DL: Yes, that was with his own daughters.

DF: Yeah. You may have read this about five or six years ago in the New York Times, his estate donated his whole archive to NYU. His daughters were close to my age, I'm 57. I think they were probably about 48 or 51 then. One of them said, “I do not want people to see the movie of me as a 12-year-old girl describing my breasts.”

DL: I know. It was a lawsuit.

DF: It was actually really cool that Times did a piece about it and NYU capitulated and said, we will give the movies back to the daughters, you know, and it was over because they looked like such horrible people. Initially, they were like, we'll just keep it in the archive for 50 years. And people can look at it after 50 years. One of the daughters is like, I have an eating disorder because of what my father did.

DL: You know, the thing about some of these artists, it’s just a general comment. You have some people who are really great artists but they're not good as human beings.

DF: Like Picasso, for example. <laugh>.

DL: Yeah. Picasso <laugh>.

DF: Picasso used to burn his girlfriend with cigarettes.

Through the forties and fifties, it sounds like the New York art community was quite supportive of each other.

DL: It was wonderful. As a kid, I felt like all of these people were my parents. I was just so happy among them. And they, everybody, treated us kids very well. There weren't very many kids. They treated us nicely.

And like Patia Rosenberg, Harold's daughter. Elaine used to, you know, go and rescue her from May, 'cause May was kind of crazy.

(1954, on 4th Avenue. Bill deKooning, Ernestine Lassaw, Elaine deKooning, Sandy Brody, Denise Lassaw, Milton Resnick, Lutz Sanders and Trissie the dog)

DF: Was May her natural mother or stepmother?

DL: May Rosenberg was her mother. May was fairly nuts. She was brilliant. You know, brilliant. She didn't give Patia much freedom. So Elaine would say, “I need Patia to help me. I'm going shopping.” And she would take Patia off to do stuff, you know? Patia and I were really good friends. She died in 2017. She was a linguist. She spoke about 10 languages, and she translated all kinds of work. She spoke Japanese and Chinese and French and Spanish and Italian. She went to Oberlin and studied Japanese folk music. She went to Japan, and she actually performed Japanese folk music in Japan.

DF: What were your impressions of Bill and Elaine de Kooning? I'm reading a sort of scandalous book, Lee Hall's biography.

DL: Oh. Don't read Lee Hall! Yeah. I was so happy when I heard she died. I hate Lee Hall.

DF: Lee Hall dredged up every bit of gossip.

DL: And she reinvents. She was supposed to be Elaine's friend. She went and she interviewed my mother, and my mother told her all kinds of stories that, you know, there was one, uh, a story about when Ibram had a job in a window display place. And he got a job for Elaine. So every morning my mother would hand him his sandwich, and he would go off to work and when he'd come back, he'd be hungry. He said, “I had to give half my sandwich to Elaine.”

DF: I knew you were gonna say that. I just got the sense that Elaine's like, oh, “Turkey…can I have half?”

DL: Well, well, it was, “Oh, food. Can I have half?” Or actually not can I, but I will have half <laugh>. And so Lee Hall changed the story and made it Pollock instead of my father. And she did that. And I don't know how much she changed stories and, and put in different characters to make it sexy or whatever.

DF: I'm a pretty intense reader. I noticed that there are no names attached to the sources. Like, she'll have a great story and it'll be an anonymous artist, or it will be a retired gallery owner, blah, blah. And I, so I'm obviously not as in tune as you are, so I don't get the references.

DL: It's a terrible book. When I see it in a used bookstore, sometimes I'll scribble on a little piece of paper. This is a bad book, <laugh> and stick it in there. But of course, I have one on the shelf, you know, because I have quite a collection of all the books about our friends.

DF: Bill and Elaine had a particularly avant-garde marriage. They obviously were very attracted to each other and loved each other. But then they immediately started having affairs with other people. And then they were physically together for about 10 years, and then they made a decision to split. But then, you know, Elaine came back to care for de Kooning when he had Alzheimer’s. They were always together, even though they physically didn't work.

DL: They never divorced. They always loved each other.

My mother would say that Bill thought he was getting a wife, like when you come home from a hard day at the studio and dinner is waiting, and the house is clean. And Elaine didn't do that.

Not long after they were married, someone she knew, a guy had a sailboat and he invited her to sail to Provincetown with him. And she couldn't say no to that adventure. So off she went. And whether she slept with him or not, I don't know. But anyway, you know, Bill was furious at that. Then they started having different lovers, but they never did divorce.

(Bill and Elaine deKooning, in the Hamptons, 1959, photo by Ibram Lassaw)

Elaine never wanted to have a baby. But [Bill’s mistress] Joan Ward got pregnant. And when Elaine went to the hospital to see the baby, and the sign said, “Mrs. De Kooning,” and she made a joke saying, oh, how nice. Bill and I always wanted to have a daughter.

Elaine was never mean to Joan. There were all these women constantly after Bill.

DF: I think Bill was dating Ruth Kligman at the same time that the baby was coming. Joan Ward having the baby sort of ended things with Ruth Kligman. I think it sounds like Ruth Kligman got on people's nerves pretty quickly like that.

DL: She did, but she wasn't a bad person. She was a groupie.

DF: Yeah, she was a groupie. There was a funny story in one of the books on Pollock. A woman artist named Stark was working with Kligman. She's still alive. Ruth Kligman wants to go meet an artist. The woman artist draws her a map to the Cedar <laugh> and says, the people you should meet there are Bill de Kooning, Franz Kline, Jackson Pollock. <laugh>. And she says later that it's almost like saying to somebody, you want to shoot a bear? Okay. A bear is a big furry thing. And you usually find them in the woods. <laugh>.

The hard life of Bill’s daughter Lisa de Kooning makes me sad, too. She was heavily involved in alcohol and drugs.

DL: She had a hard life. She had two parents that were drinking. Joan had some fancy ideas. By that time, Bill had money. And Joan once said to my mother, “My daughter is going to be a lady, not like your daughter.” She hired Priscilla Morgan to make Lisa a "lady". Priscella Morgan is the only other person whose death made me smile.

DF: Ouch. Did your mother walk the line in terms of, you know, she's close to Elaine, but she was still on speaking terms or friends with Joan Ward, the mother of Lisa?

DL: Of course. My mother was pretty neutral and calm. I mean, there were people that she preferred not to see too much. She was never mean to anybody. And she didn't say bad things about people.

DF: When Bill moved out to Springs, did Joan have a house on his property or a house on nearby property where Lisa was raised?

DL: They had a house. Bill had bought a house next to the Green River Cemetery.

DF: Is that the cemetery where Bill is buried?

DL; No, Joan buried him somewhere secret. But my parents, Frank O'Hara and Elaine, as well. And Patsy Southgate, Ossorio and Ted Dragon, Rosenberg and Jimmy Ernst. Just about everybody is there. Sometimes I used to go there, and I would take a little bottle of whiskey and a little saki cup and I would offer a little drink to everybody.

DF: Was this when you were a teenager or when you were an adult?

DL: No, this was before my mom died in 2014.

DF: Patsy Southgate seems like an interesting character. Do you know the Mike Goldberg story? They were married for like five years, Mike Goldberg and Patsy?

DL: Yeah.

DF: So Mike Goldberg was, you know, sort of a sexy dude. He had that long affair with the painter Joan Mitchell, this long tortured affair. He forged checks out of Joan Mitchell’s ex-husband Barney Rossett’s account.

DL: Right, right.

DF: So they send Mike to a mental hospital to avoid prison. And 10 or 15 years later, he's married to Patsy Southgate, living in the Hamptons, and de Kooning comes over and he's drunk. And he says to Mike Goldberg, oh yeah, go to my house. You can take two lithographs, any ones you want. And so he goes over. Right.

DL: I know that story <laugh>.

DF: And instead, Mike takes 10 lithographs and he forges de Kooning’s signature on them.

DL: Some of these people were such characters, you know.

DF: Patsy Southgate, you knew her well? She was this sort of great beauty, you know, she's married to the first one of the editors of the Paris Review.

DL: Yes, Peter Matthiessen. They had two children and both have now died.

DF: With Mike Goldberg, they put him in a psychiatric hospital to avoid prison <laugh> because of the forgeries. Then Patsy divorced him and said, well, I'm paraphrasing, of course, “I guess I was married to a sociopath for five years.” I think Frank O'Hara always had the hots for him because he had a thing for straight men.

DL: Mike was a pretty handsome guy.

DF: Goldberg was a paratrooper. He had the whole macho thing going. He was ruggedly handsome. The photos of him are pretty good.

In the early fifties, how did success change the New York art scene? Was your father able to start selling things in the early 1950s?

DL: He had this sculpture called “Milky Way” that was in the show at the Whitney.

DF: You still have that one?

DL: I do.

DF: I just found that on a website called “Story of Art” that said it was in your collection.

DL: Yeah. Ibram had that one in the show at the Whitney. And Samuel Kootz came to the Whitney and he saw it, and he asked, who is that guy, the artist who made this? And anyway, then they met and Sam said, I want you in my gallery. After Ibram had the gallery, he began to sell work. Before the gallery, he only sold one piece. It didn't make us rich. He would sell some, and then he did also these synagogue commissions, from ‘53 to ‘56, and then one much later.

DF: Was this like the New York reform synagogues?

DL: Actually none of them were in New York City. One of them was in Port Chester, which was the synagogue that Philip Johnson built.

There was one commission in Massachusetts, one in Providence, Rhode Island, one in Minneapolis. And one in Ohio.

My father's having a show at the Figge Museum in Davenport, Iowa.

So I went there in early September, and then I went to New York for about 10 or 12 days, and ran around. And then I went to Massachusetts and I gave a talk about Ibram's synagogue work at the Temple Beth-El in Springfield. Mm-Hmm.

And then I went to Providence, where there is another Temple Beth-El And I took photographs of some of the work there.

DF: I was amazed when reading about the early 1950’s art scene, how little the paintings went for. Talent 1950 was an exhibit where Clement Greenberg basically directed who went into the show. So you get Grace Hartigan and Larry Rivers. It was like 10 or 12 young artists. They sold virtually nothing in the show, even though it was a big event. Or pieces were selling for a hundred dollars.

DL: Right. They didn't sell for very much. It was good when Ibram sold something, but we never really got rich.

DF: How did your parents wind up owning a place in East Hampton?

DL: In 1954, we were in New Mexico for the summer. And my father's aunt, one of his mother's sisters, passed away. And she left this fabulous sum of $5,000 to Ibram. When we got back to New York, he decided he wanted to buy some land. And this artist's friend, I think Bill Lubin, he knew of some land out in East Hampton. There were 10 acres for sale. So then there was another artist who wanted some land. My father took five acres in the back. And the other guys split five acres. And we bought it for, I don't know, a hundred dollars an acre or something.

DF: Is this where your mother and father built a house where they moved to in ‘63?

DL: In ‘55, my father built a little 16 by 16 cabin, up on stilts. All by hand. We didn't have electricity or anything. We had a hand pump in the yard for water.

DF: Did he use this cabin as a studio or as a summer place?

DL: That was our first little house. It was only 16 by 16. And then the next year, my mother designed our house. It was passive solar with a big fireplace and the two doors to come into the house. Both came into the kitchen, so when she was cooking, she wasn't left out of the conversation. Everybody sat at the counter and could talk to her while she cooked.

And pretty much that was the house. A little part of it was a small studio. In 1973, my father had a commission for Exxon, in a big building on Sixth Avenue. And with that money, he was able to build a studio, a really big studio with a concrete floor and everything.

DF: Just the idea of five acres in East Hampton is amazing.

DL: Over the years, some of the neighbors said well, you know, I'd like to sell an acre over here that touches your property. Eventually we had 30 acres. By the time my father was in his eighties, the taxes were getting so horrible and everything, and we didn't know what to do. People wanted to develop it. We don't wanna put more houses in the woods. 'cause he loved his woods. So we did a deal with the town, and we turned, I think it was 23 acres, into a nature preserve.

DF: That's wonderful.

DL: And if you go out to Springs on School Street, there's the beginning of a trail. It's the Lassaw Nature Preserve. You could walk the trail. And if you follow that trail all the way, it connects to other parcels of land, you can walk all the way to Amagansett, to the ocean.

DF: I just remember Larry Rivers got his house for $2,500. Somebody else gave him the money. I think it was James Merrill. I can't remember the full story, but it was like, I don't know, 1950 or 1954.

Did you know, Larry's occasional lover, the crazy John Bernard Myers?

DL: Yeah, Johnny Myers.

DF: He was an amazing figure. I'm rereading his book, Tracking the Marvelous. He was a real cultural engine.

DL: He was a puppeteer. Yeah. He used to give puppet shows at the Club for us kids.

DF: I think that polio sort of destroyed his puppet business. The whole polio epidemic started, and then people are like, I don't wanna send my kid to a puppet show, so he will get polio. But Myers, he just remade himself into a gallery director. Frank O'Hara's first poetry chapbook came through the gallery. There was an exhibit with Grace Hartigan, where I guess her and O'Hara worked together to do a painting and poetry on oranges. And for the exhibit, Myers had her paint the covers of like 50 books, I guess. She painted abstract oranges on all of them. And they were sold for a dollar apiece. It was just this amazing crosspollination of poets and artists.

DL: You know, that's, that's really how things were, because none of those people had become gods. They were just people. I mean, I used to ride my bike down Fireplace Road to go to my friend Nancy's house, and Pollock would be out in the field working on a canvas that was laid out on some boards. I have a scar on my leg from his dog biting me.

DF: Was the dog not a nice dog? Or was he trying to play?

DL: He didn't like bicycles.

DF: As a child, did you know Lee Krasner and Jackson Pollock? Were they people in your parents' lives?

DL: Yeah, they lived down the road, you know, so we saw them, but they weren't close, close friends. I mean, they were close friends, but they weren't our closest friends. My father knew Lee when she was living with Igor.

DF: This was before she got together with Jackson Pollock. Igor Pantuhoff was the boyfriend that she was with in the 1930’s. Lee Krasner and Jackson Pollock got together, I think in the ‘43 or ‘45 or something.

DL: I don't remember.

DF: Did you guys have much of a relationship with Franz Kline?

DL: We saw him at parties and stuff. He died so young.

DF: Yeah. He died in ‘62 at the age of 52.

DL: The thing about being an artist’s kid is, you know, whatever your parents do is sort of boring. I was never impressed by people who were famous. A lot of our friends got famous, but we didn't take it very seriously. You know, if I had been an art historian when I was eight years old, I could really be doing something with it now.

DF: In your personal collection, you have some of your father's iconic sculptures. How do you store them? They must be somewhat fragile. Do you leave them in New York in storage or did you take them out west?

DL: When my mom died, I had this big problem, you know? There was the studio, all the artwork and East Hampton taxes.

And I actually hate East Hampton. I love the beach. I love the friends we had and the wonderful parties and all of that, which is in the past. But I don't like East Hampton itself. If I had wanted to live there, the roof needed fixing, the studio roof was leaking, the heater had gone out. I could have spent a hundred thousand dollars fixing the place up. I mean, the termites had been very happy there for a long time. But I didn't have the money. Our house was so primitive by today's standards I couldn't have even rented it. No dish washing machine, no clothes dryer, no microwave etc. There was a window that was rotting out. I still don't have a microwave or a clothes dryer. We hang laundry in the sun.

You know, I'm living in Bellingham, Washington with my partner Serge. I don't wanna live in East Hampton. Yeah. I don't like East Hampton taxes or anything. I call East Hampton, T, T and T-- ticks, tourists and taxes. So I decided to sell the place. And then with the money I made from that, I can live and take care of the artwork.

I had a storage place outside of New York City that was over $600 a month. That was actually cheap because some of the other places were $2,000 a month. I stayed in that place for a year. It was perfectly okay as a storage place, but it was totally inconvenient since I'm out on the West Coast.

In 2016, Serge and I went back to New York and we packed everything up and it cost me $12,000 to move it out West. Now I have a storage place that's just as good as the one in New York for $300 a month. That's where I keep everything. So at least it's just down the block from me. Really.

DF: It's safer, because you can monitor what's happening?

DL: I can monitor it and I can go there and I can bring sculptures home and photograph them and Mm-Hmm. <affirmative>, because I'm working on Ibram’s catalog raisonne. This is my big, big job.

DF: This is the big project that you're undertaking now?

DL: There are all kinds of other projects that kind of are sidelines of that one.

My father took a lot of stereo slides. A lot of them are mostly of his sculpture, but then there's hundreds of slides of people in places that we visited. I scanned those at very high resolution, and then I print them out. I'm gonna make a book about living in the loft, and also all of our friends.

DF: That sounds like a marvelous project.

DL: I've got a guy here who's my Photoshop guru. I do a little bit of Photoshop, but it would take me, you know, 20 years to be as good as him. And meanwhile it's easier just to hire him to do it. I need a lot of color correction or something, these slides are so old. So then I get him to do that type of work.

I have these eight-millimeter family movies, which I digitized, and now I'm going to edit them because I have movies with everybody on the beach. And there's, you know, Mike Goldberg and Norman Bluhm, and Mike Kanamatsu.

DF: Everything is connected. You mentioned the artist Mike Kanamatsu. He had an affair with Hettie Jones, who you remember.

DL: I remember Hettie Jones and Leroi Jones, you know, from when I was hanging out in the Village when I was 12, or 13.

DF: Hettie slept with Mike Kanamatsu for revenge for all of LeRoi’s affairs.

DL: Did you read her book? How I Became Hettie Jones?

DF: I've read it twice.

DL: Yeah. I have too <laugh>.

DF: It's a great book. The first time I read it, I thought, oh, LeRoi Jones was a big jerk. And then the second time I read it, I thought, my God, he was so pulled by the forces of history.

Your friend Diana Powell Ward actually introduced him to her husband, but then after he became Amiri Baraka, he ignored Diana. He couldn't talk to the white woman, but he would still talk to her husband, the playwright and director Douglas Ward.

DL: Did you read Diane di Prima's book, My Life as a Woman?

DF: I've read big chunks of it. She was an amazing figure. There's the creepy part where she, and this is in Hettie's book, that she and Diane both had LeRoi babies at the same time.

DL: Yeah.

DF: And Diane moved two blocks away from their house. And so there was sort of an aggressive quality to her. But I read big chunks of Diane’s book. There is a very funny story at the beginning of the book. Diane di Prima, was for a while a lesbian with a red crew cut.

She goes into a famous lesbian bar, Mona’s. The bouncer was a big fat Italian guy. He says to her, “Hey, you're Tony di Prima's daughter, right?” And she's like, uh, yeah. Obviously he's got Brooklyn connections. And he says, “If you ever get into trouble, come here and look for Tommy.”

DL: I remember that. I read that one.

DF: It was sort of beautiful and was sort of horrible for her that everyone knows her business, but then it's almost like a card to keep in your back pocket if you ever need muscle. There's a big guy named Tommy who will come and beat somebody up for you. <laugh>.

DL: Yeah.

DF: It was very, very primitive. It was probably the best image in the book. She was also a tough woman. She said, I want a kid. So she has sex with one of her friends and has the first child. And she doesn't even tell the guy that he's a father. Back in the mid-1950s, she had a baby by herself.

How long have you and your partner been together?

DL: Twenty years now. We're not married though.

DF: Is he an artist as well?

DL: When I met him, he was a writer. He was born in Belgium. His mother was Ukrainian and his father was Belgian, but he died in a coal mine. His stepfather was Russian, Mongolian. He became a linguist, and he taught at the University of Alaska Fairbanks for quite a few years. He taught Russian, French and Spanish.

Serge was writing novels, and he wrote some very interesting crazy novels, very surrealistic novels. The publishing industry is so horrible. He tried and tried to get published by some real publishers. He is self published.

Then about, I don't know, five years ago, he decided he was gonna paint. He's done maybe hundreds of paintings since then. They're very strange paintings. They're, they're kind of like stories. Each painting is its own story. Anyway, he is a very interesting guy.

DF: What's your partner’s name?

DL: His name is Serge. I met him in Alaska. I met him in Anchorage at a poetry reading. We were talking and it turned out he lived like a mile and a half away from me, 220 miles from where we were sitting.

DF: Were you still in the woods?

DL: Yeah, I was back in the woods. I lived in Anchorage for 12 years. After the pipeline, I moved to Anchorage and I was part of the Visual Arts Center. And then in 1979, I met a man from Tibet. We ended up getting married. We started the first Dharma Center in Alaska. We brought Tibetan lamas to give teachings, Buddhist teachings in Alaska. He was killed in an accident in 1988.

DF: I'm sorry.

DL: Then I moved down to Homer, about 220 miles from Anchorage.

I kept working for Tibet. For many years, you know, I'd go to India. I've met the Dalai Lama a whole bunch of times. We started the Alaska-Tibet Committee. If there was some big event somewhere, I would fly there and be part of it. And so that was a big part of my life. I wrote a film called “Tibet: A Moment in Time” for the filmmaker of Bill Bacon.

DF: I’m not familiar with Bill Bacon.

DL: He is dead now. He was a wildlife photographer and a filmmaker in Alaska. And then he went to Tibet kind of by accident with David Bresher. And he had all these hours and hours and hours of film of Tibet. He didn't know what to do with it, you know. I saw it and I timed the film. I said, you know, this part and that part can go together. And here's the story that we can make out of the pictures that you have.

DF: Is that film finished?

DL: I don't know if it's still available. Maybe online or something, somewhere. On the first VHS edition, I got credit, but I don't know if I got credit later. [Editor’s Note: A DVD of the film is available on Amazon.]

Bill was a funny person, and we worked on a second film together. We traveled around India and interviewed people and did all kinds of things. And then he said, I've got the film, I don't need you.

DF: A little too much hubris for a collaborator.

You have given me such great stories from the New York art world in the 1950’s.

DL: Well, you know, I call myself a mini-art historian. I didn't go to college for any of that. There were all these people that we knew that I didn't pay a whole lot of attention to. I didn't think of them as being very special.

But now I look them up in the Archives of American Art, and I read interviews that they did, and I find out like, well, what was the background? I mean, you know, we knew people like Saul Steinberg.

I never thought about, well, where did they come from? Or what were their experiences. Then I go and research all of that because I'm writing about my father. I wanna really have an in-depth understanding of the context of the times.

DF: One last question. What did you think of the Human Be-In when you were there? Were you impressed with the event? Was it a cool thing?

DL: Well, I was completely stoned on some fantastic Owsley LSD and I had a wonderful time.

DF:<laugh> I wonder if you remember most of it.

DL: No, I remember everything. I wrote a story about it. I'll send it to you.

DF: That would be great. I have been doing a lot of research on Ken Kesey and the Merry Pranksters. I'm a pretty square dude, I think, so I'm not such a fan of him, you know, and his treatment of women.

DL: I'm not either. And actually the more that I learn about some of these people, I don't admire them at all. I think a lot of 'em were really screwed up people.

DF: Yeah. A lot of it for me involves the treatment of women, you know. On the bus trips, the Pranksters picked up underage hitchhikers for sex and things like that. What kind of decision should a 15-year-old girl be making, or what are the conditions that they're in?

DL: Well, speaking as a 15-year-old girl, yeah. They have their own ideas. I mean, they may not have much experience in the world, but they're not completely innocent.

DF: It also depends on the maturity of the individual and the circumstances and how their decisions are influenced. It was wonderful talking to you, Denise, and I really appreciate you taking all this time with me.

DL: Okay.

DF: You have some great stories. What, what is your partner's last name, if I may ask?

DL: It's L-E-C-O-M-T-E. I use my own name. We're not married.

DF: You have a great name. You have a lot of history behind it, so I wouldn't give that up.

DL: No, I don't plan to.