(Jack Dowling in his loft in the 1967)

Jack Dowling, a writer and painter, was born in New Jersey in 1931. As a 12-year-old, he would take the ferry from his hometown of Sewaren, biking around and exploring New York City. At the age of 18, he received a scholarship to the elite Cooper Union, the art and architecture school in Greenwich Village. He moved to New York in 1950, never looking back.

Jack became a successful painter and obtained a loft on East 24th Street, where he painted and sold his art. In 1971, New York City took the loft by eminent domain, Jack found himself homeless and unemployed, his paintings in storage. Twenty years after he came to New York, Jack was back where he started, 40 years old and working in the mailroom, this time at Colt Studios, a troubled mail-order photo agency that sent photographs of male nudes around the United States.

In chaos, there is opportunity. Jack went from mailboy to partner in two years, and revolutionized the product Colt was selling. Gay men didn’t want pictures any longer of men in togas, but preferred the modern look of men dressed in leather with facial hair, men in dungarees. Colt exploded after these changes. For Jack, his decade at Colt was quite lucrative and life transforming.

In his youth, Jack Dowling cut a striking figure in Greenwich Village, with a handsome, high-cheekboned face and a preternaturally slim and muscular physique. At 88, he is still handsome and slim. From his gorgeous studio apartment in the Westbeth artists’ community, where he has lived since 1972, Jack spoke of the wild 1970s in the Village.

At Westbeth, Jack is an institution, running the Westbeth Gallery for 14 years, from March 1998 to March 2012. He is still on the admissions committee.

At Westbeth, Jack is an institution, running the Westbeth Gallery for 14 years, from March 1998 to March 2012. He is still on the admissions committee.

(View of Westbeth from West Drive)

(Westbeth)

DYLAN FOLEY: Did Westbeth suffer flooding during Hurricane Sandy in 2009?

JACK DOWLING: The basement got 9 feet.

Not only did the artists who had studios get flooded, but the building management lost the Westbeth records.

DF: Were these the applications and personal statements?

JD:Yes. You had to do more than that. You had to prove you were a working artist. I’m on the admissions committee. It’s the one I remain on. It’s very, very tricky. We are rent stabilized, where people think they can end their days. We get artists applying and I look at the dates of their shows and if they are really far back. I look at where they are living now, if they seem to be secure. If its someone who is 70 years old and they are pumping out art and have shows everywhere, that’s fine.

In the case of somebody who is 65 and they haven’t painted since they were 45 and that’s the only reference, or when their last exhibit was 20 years ago, its problematic. Trying to get young people in the building is very hard because there are all these people in front of them.

Jack Dowling, Ladies in America, 1967)

DF: I do see more young people in the building. Do young people inherit their parents’ apartments?

JD:That’s very few. Most of the young people you see are from Martha Graham’s dance studio.

You have to go online and put his name in. I remember a name, Greta Sultan. She was a pianist who interpreted and played a lot of John Cage’s work. She’s on YouTube. I found her name on the original Westbeth tenant’s list. She died a long time ago.

DF: Did you know the difficult Westbeth resident, the pianist Patti Bown?

JD: She had a double kind of thing—Hi honey, how are you?” And then…

DF: What was happening in your life when you were 40 years old?

JD: I had been to that loft on First Avenue and 24thStreet over the years before. Two people I knew had it. I loved it. It was enormous. Those guys were not painters. One worked at Look Magazine and the other worked for a department store. I said, If you ever give this up, let me know. Before they had been tenants, the loft had been used by the Paper Bag Players as a rehearsal place and as a living space for some of the members.

They did call me one day and said, “We are moving.” I said, “How much do you want?” It was key money days. They came back to me in a day of two said, “We are going to ask you for $285.” It was the stove and other things that they had installed. I thought, that’s easy, $285 for that place. Not that I had the money. I agreed.

I had a friend staying with me, who sort of liked to think of himself as my boyfriend. We were living at 641 Hudson. We were back in that building again At Horatio. I lived there before I went to Europe in 1958 after graduating from Cooper Union. An apartment had become vacant when I got back. I told him I was going to the loft by myself. I moved into the loft in ’61. I would have been 31. That’s where I actually started painting seriously. I painted in Italy when I was teaching. They were nice interesting abstract paintings, but I was just knocking them off.

The one thing I did know was that the loft was sitting on Title I land, which meant that the land could only be used for public housing. That is what gave them the right to tear down the existing structure. I saw that as being way off in the future. The city was buying up pieces of property that was in an area that was called Bellevue South. It runs from 23rdStreet all the way up to 32ndStreet. My loft was on 1stAvenue and 24thStreet. I was across the street from the veteran’s hospital. With that understanding, I bought the loft. I was paying $100 to the man who owned it.

My painting career really grew there. Eventually, I had the support of Ivan Karp at the Leo Castelli Gallery. He was the director of the Leo Castelli Gallery. He put me into a lot of shows although he didn’t offer me a show at Castelli.

(Jack Dowling, Crossing Over, 1967)

The city was demolishing buildings two blocks away from me. I got a Legal Aid attorney. He found out that they city was going to give the building to NYU. That’s totally illegal. I took it to court and that court case went on for over two years.

It cost me money because I wasn’t painting and didn’t have any money coming in.

That’s when I got the part-time job as a mailboy at Colt Studios, three days a week. All of a sudden, things happened real fast in court. I was given three days to get out. I had all my stuff, all these things from the ‘50’s—books, records, music equipment, furniture.

(Jack Dowling in the 1950's)

I called everyone I knew. The city recognized the loft space as commercial, so they were required to put the paintings in storage. I got some compensation, under $2,000. I called all my friends and said, “Come get my stuff.” I slipped books into the painting storage. I had two cats and gave one to a friend and kept the other one. I was working at Colt part time and they had a space on Barrow Street. I was sleeping there sometimes. A friend of mine who lived on Leroy Street was way for the summer, so I stayed there.

I was never on the list to get into Westbeth, but I had a Department of Cultural Affairs certificate that I was an artist-in-residence. It started in Soho, where they recognized the legality of the artists living in the lofts. I got a call to come over here to Westbeth. I was a man called Dickson Bane, one of the early administrators. He said that the city had contacted him and asked him if there was any space for me.

DF: Was this a guilt-wracked administrator?

JD: I did establish a relationship with the man from the city who was responsible for getting me out of the loft. He kept finding me one-bedroom apartments in odd neighborhoods, that would be impossible for a painter to live in, to work in or to carry materials in. There were still a lot of good low-rent neighborhoods in the 1970’s. The apartments were not suitable for a painter. I had to turn them all down.

I had a motorcycle, a big, heavy Motoguzzi. In the entry of the loft building on First Avenue, it was big enough that I could park it there, lock the front door and the bike was there. It was safe.

One day. I went there and the bike was gone. I went to the deli downstairs and they said the city workers had come and taken it. They had a garage on 27thStreet.

I went to 27thStreet and I walked in. There were guys standing around. I saw my bike in the back. They had stole it. That’s my bike, I said. “I’m taking it.” “I’m taking it out of here. The guy who I had the ongoing relationship which was there. I could have called the cops. They would have tried to sell it. I rode it out of the garage. He saw the whole thing. He knew that I did not want to make trouble for those guys. They were the guys who worked for him. I just wanted my bike back. He knew NYU was getting the property.

There were three things that happened—I was homeless, I was working for Colt. I could see the mistakes they were making at Colt and how badly they were promoting themselves.

I was in debt and the apartment they gave me in Westbeth was 359 square feet. Tiny little place. When I had my paintings delivered there. They took up half the apartment. There was my bed, my kitchen and that was it. I couldn’t paint in the space. I couldn’t even stand back to see what I was doing. I did get, maybe a year later, a studio on the 3rdfloor, where I moved all the paintings, but by that time, I had essentially stopped painting. I had lost my connection with Ivan Karp, because nothing was going on. I was 40 and I could see that I could make some money at Colt. So I put my energies into that and never really realized that I would be good at figuring out how a business should be run and how this business was not being run. There was competition between the two guys who owned and I was hired. After I became more full time Colt, I gave them some suggestions and found them a new space [for the company]. They offered me a junior partnership. I took that, which increased my salary.

(Jack Dowling, left, on Fire Island)

DF: You started in the mailroom?

JD: Yeah, I started as the mailboy. I was getting maybe 75 dollars [a week].

DF: Did you have to buy a chunk of the company?

JD: They asked if I would commit to being there for three years and they made me a junior partner. Then when Lou Thomas left, it turned out that yes, I am a partner. It was Lou Thomas and Jim French, who produced all the photographs. Everything was sent to New York, to be processed, approved and sent out again.

I came up with a lot of good moneymaking ideas. We made a lot of money.

DF: Jim French was shooting a particular kind of image, like buff men, body builder types. You wanted a more modern look?

JD: Jim started out drawing, then he became the photographer. He became one of the leading nude male photographers in California. Lou was here in New York. Lou competed with Jim by taking photos. Jim resented that. He called it his company. He called it his company. They had this falling out. Eventually Lou decided to leave. We had enough money to buy him out at $50,000. He formed Target Studios and a disco. He had a very crazy lover called the Swamp Lady, a tall rangy man from the South Africa, a blonde 6-foot tall, shambly, crazy guy. They opened up a disco south of Houston called Frankenstein. Within two years, both failed.

I built the house on Fire Island. I paid for it in stages.

Jim would call me at 1am or 2am on Sunday. He’d have a great idea. I drank a lot in those days. At one point, I told him to stop fucking calling me at that hour. He took that badly.

I’d fly to London to try to stop the copying of Colt material there. They were bootlegging. The copies were terrible. They were very bad.

DF: Who was the big iconic model of Colt studios?

JD: His real name was Occum. He was a model we discovered who photographed really beautifully.

JD: His real name was Occum. He was a model we discovered who photographed really beautifully.

We had no contracts on anybody.

He was about 5’6” or 5’7”, sexy as hell, with a beautiful cock on him. Another photographer said, he’d never met anybody whose skin photographed as beautifully. I might be related to him. His name was Occum and on the Indian line going way back, my great-great-great-great grandfather was Sampson Occum. The skin tone might have come from that. He was permanently tan, naturally and it had a sheen to it.

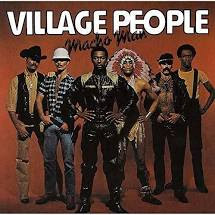

All the guys running around the streets were wearing cutoffs and boots. You couldn’t get into the Eagle’s Nest unless you were dressed like that. Sometimes a guy would come in wearing a hardhat, trying to look like a rigger. Costume time. We did that photograph. There was no Village People. On the back of the album, it says “Thanks to Colt Industries.”

DF: Was the Village People a real band?

JD: No. Not at all. Whoever put this group together recorded these songs with pick-up artists. They came to Colt Studios. He wanted to have a mix of Village looking guys. Joseph, who worked for me packing orders, hung out in the Village and knew a lot of guys. One of those guys in the picture also worked for me. He was a mailboy. Joe rounded up some of the guys he knew. He put an Indian headdress on one. He got a black fellow he knew. He posed them in front of the old Ramrod Bar on West Street and took the picture that became the cover and has remained the cover for eons.

The song took off, especially “YMCA.” The guys in the photo were Village people, but not The Village People. It’s never really come out who the performers were. They were pick-up people. They sang the songs and dispersed.

Jim and I were coming to a head. Jim always considered Colt to be his company, even though we were splitting the profits 50-50. He decided he wanted the company to be in California and didn’t want the company to be associated with me anymore.

He went to a man in New York who owned a number of magazines, including Blue Boy. Jim offered Colt Studios to him and he named a price. They decided they didn’t want to take over Colt, because they were already buying photos from other people.

Jim said he was going to buy me out. I got a letter from his attorney, George Towers. Jim said that the lawyer said he had to pay me one half the price that Jim had offered to sell it to Blueboy. As half owner, I was due $100,000. I thought to myself, should I get an attorney or should I get out of this and put it behind me? I decided to go with the deal, to send everything out to California, including files that were 10, 15 or 20 years old, but Jim was so paranoid, he wanted very last paperclip Everything was sent out there in ’78.

The Fire Island house was already in progression. I’d laid out $40,000. I took a mortgage for the balance of the construction, but paid it off in three years. The house was free and clear.

I had a collection of the small portrait books. I had copies of Man,Another Manand Olympus. I decided to sell them on Ebay. I had photographs and drawing that Jim had sent me as samples. There is not one piece of Colt in this apartment. If, when I had started at Colt as the mailboy, if I had kept a copy of everything we produced, it would be worth millions today.

DF: Are you referring to Colt’s small magazines?

JD: The small ones are worth more. They sell for more.

DF: You were dating a porn star?

JD: I wasn’t dating him. He was my lover. It had nothing to do with Colt. He wasn’t a porn star. He was an antique dealer. I met him in the bar.

In the New Yorker last year, there was an article on photographer Peter Lujar. The article opens with a photograph of a man lying on the Christopher Street pier; you can’t see his face. It was Stanley.

I met Stanley in the bar. I had seen him around on the docks or in another bar. He was always looking at me. I went up to him in the Eagle. I had my motorcycle with me. I said, “Everywhere I go, you are always staring at me. Why?” “I like you,” he said. “You don’t even know me and you like me.” “I like what I see,” he said.

He was in his early 20’s and I was in my early 30’s. “I said, “You want to come home with me?” I was living in a friend’s apartment on Leroy Street. I said, “Ever been on a bike?” He said no. I said, “Just lean when I lean.” We were together 17 years. This was ’72 to ’88. Stanley was very popular. He was in his early 20’s. There was a 12-year difference. I knew he was screwing around. That was the pattern. I never lived with him. I helped buy him a house in Beacon., so he could expand his antique business. It was $27,000 in the late ‘70’s. Sometimes I would come up and there’d be some guy in the backyard working on something and Stanley would say, “I am trying to teach him how to refinish.” Yeah, sure, I thought.

Somewhere along the line, Stanley ran into somebody who made films. He convinced Stanley to make a film with Jack Wrangler, the big porn star of the time. I walk into the Eagle’s Nest, I glance up and there’s this Jack Wrangler film up there and Stanley comes into the scene. I hear the two guys standing next to me say, “He’s hot and he’s playing pool in the next room.” I walked into the next room and there indeed was Stanley playing pool. I said, “You know anything about this? You never told me about making this movie.” “Well, maybe they paid me for it.” I said, “Don’t you ever make another movie again.” He said he didn’t want to again, because he didn’t like being told what to do…”Go down on him now. Suck his dick.”

I went to Jack Modaco, who owned the bar. It was on 21st and 11th. I asked Jack, could you please stop showing that film again? He agreed.

DF: After Colt, how did you survive?

JD: I built the house as an investment and rented it out. I bought the Beacon house. I bought another house on Fire Island for $53,000. I fixed that up and sold it in a year for over $100,000. I went to Key West and bought a house for $37,000, held it for a couple of years and sold it for $100,000.

With Colt, I didn’t get $100,000 at once. I got $25,000, then a thousand dollars a month for three years.

I would get art jobs. I did a whole lot of faux marb for rich Park Avenue ladies that paid very well. There was a big wave in the ‘80’s. Some jobs paid $5,000 or $6,000 for the lobby. I was very good at it.

The money was coming in from the rental house. I met Wallace and he wanted to spend time out there in the summer. Wally took early retirement from the State of New York. He was a socialworker, but went into the administration and worked his way up. The last five years, he got tiered up very well.

Wallace had to sell a brownstone he owned on Jane Street with his former lover. The ex-lover got into deep drug debt, the kind of debt you can’t ignore. So the house had to be sold.

DF: What happened to Stanley?

JD: Stanley died of AIDS in October 1988. He had the wasting syndrome. That’s all he had. He lived in the house in Beacon, scooting around in a chair with wheels.

He had a sister in Colorado. I got a call from him. “I feel bad.” He never used that word. I went up to Beacon. The nurse was there. The nurse said, “You have to put him in the hospital.” He always wanted to die at home. We put him in Vassar Hospital in Poughkeepsie. He died within four or five days. He went from a guy that was 145 or 150 pounds to barely a hundred.

This was ’88. I spent a year trying to figure out what to do with the house and his collection. He had no recordkeeping whatsoever, what was his, what was on consignment. He had three checking accounts. If he was overdrafted, he would go to open another checking account.

Stanley was in the last stage that happened to many gay men where they are going to die, they spend out their retirement funds or would max out their credit cards. They knew they would die they before it had to be paid.

It took me a long time to sort things out. He was a specialist in Hudson Valley furniture. His sister started claiming that things were hers or her mother’s. He had given her his half of the house. While Stanley was alive, she was telling him to his face she was taking certain things.

I got a call from Stanley. “Come up here.” We went to his attorney. “I’m cutting her out of the will.”

When she showed up after his death, I told her that the contents of the house belonged to me, but I would give her the cut-glass collections, like punch bowls and decorative glass. It was very valuable, worth over $10,000.

She packed everything up in Stanley’s truck and I never heard from her again.

DF: Where did you grow up?

JD: We grew up in a great Victorian house on the Arthur Kill in New Jersey. The Arthur Kill is the piece of water that separates Staten Island from New Jersey.

Sewaren was a very small town that had been a high-end resort town for people from New York. They were big houses. Our living room was 40-feet long. Now the town has rebuilt the old waterfront.

There had been a dock where steamboats from New York would come. They would bring people from the Battery.

Our house had been broken down into rooms for seamen.

DF: When did you come to New York?

JD: Even though I had the Cooper Union scholarship since 1951, I kept making excuses not to go. I came here in late 1950 or ’51. I knew I’d be coming to New York for a long time.

DF: Where did you first live in New York?

JD: My first place in Manhattan was a 7-dollar-a-week rented room on East 58thStreet between First and Second Avenues. Like the Village, all the houses had been broken up into rooming houses. All the grand houses over here on Horatio Street were workingmen’s houses. Streets like Horatio Street or Jane Street had no trees on them. They were working-class streets, very Irish. The docks were all going full blast. The warehouses were all there.

DF: When did the West Side docks die?

JD: They were still operating when I was ln 641 Hudson. In the 1950’s, they were still bringing the freight trains over. The freight trains were running to Pier 40. What was killed by the World Trade Center was the cheese market. There were dozens of cheese stores. There was Radio Row, where they would buy and sell radios. There were lots of small businesses that were specialized.

DF: What do you know about the 7thAvenue extension?

JD: The traffic going down 7thAvenue would go down Greenwich Avenue. There was a big warehouse right there. If you go down 7thAvenue, you’ll see that all the buildings are sheared off.

The railroad coming through Westbeth was built in the 1930’s. They got the train off 11th Avenue because it was killing people.

When I moved into Westbeth, the tracks still went down Christopher Street, where the trucks were parked under them and the gay boys played. There was a pony ride for kids and there was parking under the old Miller Highway. It was a very gritty, gritty neighborhood.

Not many people had cars in the city in the 1950’s. I could park anywhere. When I drove my car out to Fire Island in 1956, there were no cars by the boat launch. The boat was getting ready to leave. It was a 10 o’clock boat. “What should I do with my car?” “Just leave it there,” they said.

I am hoping that I can be out on Fire Island for most of the summer and that’s it. Then it’s going on the market. The house across the street from me, on the by, old for one million, two-hundred thousand.

My house cost $62,000 to build. I’m 15 feet above sea level. I’m on the third dune.

The model was Andrew Occum. Most of the models went from AIDS.

When Colt moved into porn, not long after I left, Jim opened up another company called Buckshot. They were doing hardcore porn. That’s long before anyone thought of using condoms. I didn’t want anything to do with porn.

No comments:

Post a Comment