(Ann Bannon in the 1955)

--Interview by Dylan Foley

In the mid-1950’s, a Philadelphia housewife named Ann Bannon walked nervously into a local pharmacy. She went to the rack of pulp novels and pulled out a stack of books, some detective novels, and the forbidden fruit, a novel called Spring Fire by Vin Packer, which was a college romance between two women.

Bannon devoured Spring Fire and realized she might be able to write an erotic pulp novel of her own. After she finished writing her novel, she wrote Vin Packer, whose real name is Marijane Meaker, asking her for advice. Intrigued by Bannon’s letter and her manuscript, Meaker invited her to Greenwich Village.

After Bannon finally convinced her reluctant husband to let her go to New York, Bannon gave her manuscript to Dick Carroll, the editor of Gold Medal Books, which was hungry to publish more lesbian pulp novels.

This was 1956. Meaker took Bannon on a tour of Greenwich Village, showing her the lesbian bars and taking her to the Bagatelle, the most popular lesbian bar in the Village. Meaker initiated Bannon into the Village gay culture, guiding her through the butch/femme dynamic, and the language and dress used by gay women in the 1950’s. Though no romance occurred on this trip, it allowed Bannon to explore her own sexuality.

At the end of her visit, Dick Carroll gave Bannon her manuscript, told her to cut it down and to put the erotic and romantic relationship between the college girls front and center.

Bannon’s resulting 1957 pulp novel Odd Girl Out was a bestseller, giving Bannon $30,000 in royalties, which would be worth $279,000 in 2020 dollars.

Bannon (which is a pseudonym) made numerous research trips to Greenwich Village, even after she and her husband moved to California and had two daughters. Bannon finally developed her most striking hero, Beebo Brinker, who Bannon has referred to as a “butch buccaneer,” a fearless, capable young lesbian who is the romantic object desire of other lesbians in the Village.

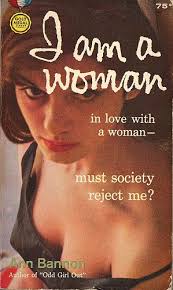

Bannon was born in 1932 and raised in Illinois. She went to college at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, and lived in Philadelphia and southern California, finally settling in Sacramento. Photos from the 1950’s show Ann Bannon as a striking, pretty blonde with high cheekbones and a warm smile. Her other books include I Am a Woman, Women in the Shadows, Journey to a Woman(1960), The Marriage, and Beebo Brinker. Journey to a Woman was the most autobiographical novel, where a married woman living in California travels to Greenwich Village to find her lost lover.

Bannon published her last book Beebo Brinker in 1962. At that point, Bannon returned to school, to get a teaching credential that would lead to self-sufficiency and the ability to end her unhappy marriage. Bannon wound up getting a masters, then a PhD in linguistics from Stanford. She was a professor and a dean at Cal State Sacramento from 1973 to 1997. Bannon’s marriage ended in 1981.

Though Bannon had stopped writing novels, the publishers did not forget Beebo Brinker. The Arno Press republished four of her novels in 1975, then in 1983, the lesbian-owned Naiad Press republished the novels. Bannon made appearances at packed bookstore readings.

In 2002, the Cleis Press republished five of the novels in 2002, with new introductions by Bannon. In 2007, two women playwrights—Kate Moira Ryan and Linda S. Chapman—converted the novels into “The Beebo Brinker Chronicles,” a critical off-Broadway hit, which got a rave review in the New York Times. Efforts to bring the play to TV as a possible miniseries are in the works.

I spoke with Ann Bannon by telephone at her home in Sacramento, where she was living under California’s “shelter in place” decree.

At 87, Bannon was a generous and candid interview subject, talking with great wit and introspection about what propelled her to take the plunge in 1956 to visit Greenwich Village and to write her six novels.

DYLAN FOLEY: How are you handling the “shelter in place” order in Sacramento?

ANN BANNON: My daughters live in the same neighborhood. One of them is having work done on her home, which is a couple of miles down the road, so she is staying nearby; the other is living with me for the duration. She’s back in Sacramento again, after nearly 30 years in the Pacific Northwest, which is a joy for all of us. So I have company. It is the first time we have been in hailing distance of each other for a long time.

DF: There is such warmth in your personal writing, when you describe your research in Greenwich Village in the 1950’s.

AB: I am glad that the writing comes across as warm. I remember these years with a kind of affection, difficult as they were.

DF: To start from the beginning, there is a great description of you buying your first lesbian pulp novel at a local pharmacy in the 1950’s. It was Vin Packer’s Spring Fire. What was the back story?

AB: I had developed an interest when I was still in college and it was very difficult to find any literature on the gay community. I don’t think you could have described more than half a dozen places in the country that had a gay community. It was so loosely organized and so cautious and hidden. When you wanted information, you went to the library. You couldn’t go anywhere else. You couldn’t go to the family doctor…he could call your parents. You couldn’t go to a counselor at school. They would call the family doctor. Your minister? Disaster! To whom would you turn? What authority figure could be counted on to be discreet? You went to the library and had to be admitted to the books [stacks] that were sequestered from the general population. It was too scary to let ordinary people read the medical books, which in any case were terribly distorted. It was an era when gay people were regarded as ill. Not only that, but homosexuality was viewed as contagious.

When I was in college, I tried getting a professor to let me into the cage where the sequestered books were. I did get in, but there was almost nothing there. All of a sudden, a year or two after I graduated, the number of venues expanded, the newsstands, the drugstores, the train stations, the airports, wherever little books were sold to keep travelers intrigued to pass the time. It began to be a new genre. The science fiction stories, the cops and robbers, the cowboys, and a few gay books.

I was already interested, so I picked up a few. It was embarrassing to do that. It was a kind of contaminated topic. You were revealing yourself, whether you meant to or not, just by choosing. I decided to put one of these gay books between some innocuous detective stories or whatever you might be using to dissemble. Doing it that way, it might not be embarrassing if the clerk knew your parents. I was an adult by this time. I was married.

One of the books I picked up was a college story. I was so young. I thought of myself as sophisticated because I had a college degree. I didn’t really have knowledge of the world that would allow me to think that way.

I really couldn’t have written about much else except my own experience, which was the college world.

The book I bought was Spring Fire by Marijane Meaker. That kicked it off. It was a disorienting experience, I guess, scary and difficult. But that book was a goldmine.

DF: You had this “Eureka” moment, where you realized that you were a good writer and could write a similar book.

AB: I finished her book and I was full of energy. Marijane’s book was very well written. She is a very different writer than I am, very practical and straightforward, with a great deal less emotional color in her writing. The end of the book was dreadful, where she had disasters visited on the two women who were at the center of the story. That was dictated by the morality cops in Congress. The paperbacks were allowed to be distributed, but only in the way that magazines were distributed, which means they were delivered in big trucks and given to the drugstore clerks to distribute on the shelves. They couldn’t be anything that could lead you astray. They were difficult books to handle.

Marijane was very lucky to get into print when she did—although her drive and talent would have gotten her there soon. She made it in because a hardcover book had been recently brought out as a paperback by Gold Medal Books. To everyone’s astonishment, it sold very well. It was called Women’s Barracks by Tereska Torres. Tereska always swore up and down that she had no interest in women and had no idea why her book had such a wide audience. That kind of energized the people at the top of Gold Medal, especially Dick Carroll, the editor. He was interested in bringing out something along those lines.

Marijane, who was a copy editor, I think, at Gold Medal at the time, volunteered, saying I know I can do this. She sat down and wrote Spring Fire. Dick gave her the title. There was a James Michener book back then called The Fires of Spring. They were riding on his coattails a bit. [Editor’s note: The writers had no control over titles or covers. The covers invariably showed two women, one possibly sultry and disheveled. Sometimes there was a rumpled bed. Many of the buyers of the lesbian pulp novels were men.]

Spring Fire was a huge success. Gold Medal did not have anything to follow it up with, until I wrote to Marijane and said, “I think I can do this, too.” Sticking to the template she had developed, I wrote a college novel. I really couldn’t have branched out much further. I hadn’t been in any of the few gay centers available to me. I looked around. We were in Philadelphia. They were in the poor parts of town. I was a young woman alone, walking around down there. It was frightening. I kind of gave up on that. I thought, Marijane could help me. I took it upon myself to write to her.

DF: Did you couch surf? Did you wind up staying with Marijane Meaker?

AB: Yes, I did. I wasn’t supposed to. I assured my husband that I would be staying at a women’s hotel. This was reassuring for him. I did have a reservation, but Marijane invited me to spend time with her.

The reason she asked me to come was that I could write. My writing was up to a certain level. At the time, she was inundated with letters from all parts of the country. Shortly thereafter, I was, too, when my first book came out. I was a little dismayed by the weak grip on English syntax and vocabulary that these young writers had. They tried and they had made an effort.

Marijane recognized in me that there might be something there. I also had a manuscript. She was intrigued.

It took me a considerable amount of time to persuade my husband that this was a good thing. We were in Philadelphia. New York was 90 minutes away by train. He yielded, but very unwillingly. He gave me some strange travelers’ checks, which were not American Express. There were no credit cards at that time—at least none issued to women in their own names.

Marijane was very kind, invited me in and showed me around. She gave my manuscript to Dick Carroll, the editor in chief. He said he’d read it right away, probably because he thought there would be a publishable book in it. While he was busy reading it, she was showing me around Greenwich Village.

DF: What was your impression of Greenwich Village?

AB: It was far different from my hometown in Illinois, which had lovely old tree-lined streets, green lawns and big old Victorians. Stepping out of Pennsylvania Station and going down to Greenwich Village, I really was Dorothy in Munchkinland. It didn’t look that way. It was not long after World War II, about a decade. It was slowly recovering from that. It had never been the toniest part of town, but it was bohemian. That’s what made it so much fun. Everyone could afford to live there. If you could afford New York at all, that’s where you went. If you were a college kid, a young artist starting out, an entertainer, all those creative areas, then that’s where you wanted to be. My god, Peter Paul and Mary would be rehearsing. You’d hear the music coming out in the middle of the day. It was a lovely place to be. I was greatly attracted to it.

Delightful as it was, it was like sneaking away to the Land of Oz. It was this wonderful place that was encouraging creative work. Everyone was writing a novel, founding a music group or creating art. It was the kind of life you dreamed about, like Paris in the 1920s. So you didn’t want to leave.

DF: You went to the Bagatelle, located at 86 University Place, at that time the most well-known lesbian bar in the city. Could you describe it?

AB: Marijane Meaker took me there. It was very well known and had a run of about seven or eight years. It was the place to be. It had a little dance floor and when you turned to the right, there was the bar. There was always a row of men dressed in suits, who were tolerated and referred to as the johns. They hadn’t come to make trouble. They had come there and wanted to watch the girls dance. As far as I know, they behaved themselves pretty well.

DF: Was there a butch-femme dynamic at the bar?

AB: That was evident immediately. I was reminded by a remark from a comedian recently. When she came out, she didn’t know anything about this dichotomy between butch and femme. She was challenged: are you butch or femme? “I don’t know, what’s the difference?” Well, you know, the femme does the laundry, does the dishes and takes out the garbage. Without hesitation she said, “I’m a butch!”

I think the butches were very much modeled on the working-class high school boys of the city in that era, the toughest kids you could dream of. The women did wear jeans in a day where jeans to fit women were not manufactured. You had to buy men’s jeans, but they were being worn by the women, along with lumberjack shirts and big sweaters. The femmes, you could not tell them apart from any college girl. Somehow, that was all we knew. There had to be some distinction. I suppose there was a biological foundation for some of it, but it was dismissed by the second wave of feminism. This was a straightjacket, an emotional and psychological constraint on how women could be and how women could be in their lives. For a long time, people were ashamed to take pleasure in these roles. Now I think they are accepted as part of the range. We learned from Dr. Kinsey that people can be people in a whole lot of different ways, no matter what their sexual orientation is.

That was the prevailing model on the dance floor and elsewhere in the bar. The femmes didn’t ask the butches to dance as a general rule. It was the butches who would come after them.

DF: For you, was interacting in the lesbian bars like learning a new language?

AB: Oh, definitely. I clutched Marijane’s coattails. I really didn’t know how to conduct myself. I didn’t even know what the word lesbian meant. She had a much more butch personality, but she presented herself in skirts and high heels.

Years later, I learned that the romance [between Meaker and the novelist Patricia Highsmith] was going on when I was travelling back and forth between New York and was staying with Marijane. I think it only lasted a couple of years with Patricia.

DF: Were you able to come back to New York multiple times?

AB: Yes, I would say six or eight times, usually for a week or 10 days, sometimes for a couple of weeks. I did have other friends, college friends or friends from my hometown living in New York or on Long Island. I had options of places where I could stay. I spent an awful lot of time in the Village. I made friends down there, too.

DF: Did you visit any bars beside the Bagatelle, like the Sea Colony?

AB: Yes. The Seven Steps Down, the Sea Colony, Sevilla, Fedora’s. I can’t remember all the names.

DF: Did women at the bars ask you to dance or make romantic overtures at you?

AB: Yees… there was some of that, and it was kind of thrilling, but I was married and we were planning on children. That’s what everybody did. You had to have a life, you felt like you had to meet the expectations of your family and your parents. One of the awful things about being a gay person in the 1950’s was that the prevailing expectation we all accepted before we knew any better was that your parents had somehow horribly messed up or otherwise you would not be tempted in that direction. If it turned out you were gay, your parents were horrified and guilty.

It was one of the reasons why people got kicked out of their homes. It was a living reproach to failed parenthood.

DF: When you were in your thrilling first visit to Greenwich Village in 1956, did you think of casting off your marriage and staying?

AB: I did, but could not imagine how to proceed with my life, especially with the prospect of children in the picture.

DF: In your novels, you write honestly about unsettling issues in the 1950’s lesbian community, like domestic violence, racism and internalized homophobia. There was also street violence against lesbians.

AB: As I did spend more time there and learned more. Imagine what it meant to me and how I soaked up everything I could. As I became acquainted with people who were living in the Village and made friendships, I began to realize that I had idealized this a little bit. Despite having a grip on the emotional life, I hadn’t realized how wrong it could go, how competitive the butch women could be, how intense these roles could be, how intense those roles were, that confined you. That was a correct perception.

People preyed on those young folks, both the men and the women. You were at risk if you were walking home late at night from a party or a pub. You could be attacked, you could be hurt, lots of bad things could happen.

The Mafia were not nice folks. They were in charge of the bars. The cops were in cahoots with the bars, because they got a payback. The whole thing was pretty corrupt. The occasional domestic violence story, that was awful to learn about, but it happened. People don’t live together without the occasional disagreements. No matter how much they love each other, there are going to be times when they are angry with each other. So that came out in strange ways, hurt and violence.

The high school kids would come into town, looking for trouble. They would threaten people and feel tough. Adolescent boys have a great need to feel power.

DF: Do you have any memory of how many copies of your books you sold?

AB: I am not sure of the numbers, but when Odd Girl Out was published, that was the bestseller of the bunch. It came out in 1957. It had to be pretty darn good because I made $30,000.[Editor’s note: According to various calculators on Google, $30,000 in 1957 dollars is worth $279,000 in 2020 dollars.]

DF: How much in royalties did you make off each 50-cent copy?

AB: I think it was about two cents. But they paid you upfront before the royalties would accumulate. You’d get $2500. That would cover the first run. Then, if it was selling well, you’d get two cents a book. [Editor’s note: At five cents a copy for royalties, with Bannon making $30,000 in royalties, it is possible that 600,000 copies were sold.]

DF: You moved to California in the late 1950’s with your husband. Did you have your daughters there and were you able to continue going to Greenwich Village for research on Beebo Brinker and her crew?

AB: We did it pronto after we got to California. I was still going back to the Village, to visit Marijane and other friends.

I stayed with some Columbia students on the Upper West Side while finishing I Am a Woman. I didn’t give up. I continued to visit. In between babies, it got a little complicated. I hated to give it up.

The paperback publishers were selling a lot of books to the movies. I think 30 or 32 movies came from Gold Medal Books, mostly cops and robbers, detective stories. Dick Carroll was out in California for the first two years, sadly in bad health. He had been a writer for films.

Knox Burger succeeded Dick. When the books came out, I got to go over to the Beverly Hills Hotel for lunch when Knox was visiting L.A.. There would be interesting people.

DF: What kind of child care allowed you to return to New York?

AB: It wasn’t ideal and I didn’t like it, but I had kind neighbors and one of them had a sister-in-law, an English lady, who was very sweet, who would stay with them. Finally, my husband would get fed up, as a way of reproaching me for disappearing for a while. He would send them packing and would take care of the kids.

DF: Your last book Beebo Brinker was published in 1962. What was the reason you stopped writing fiction?

AB: I had to get back to college. I wanted to get an advanced degree. I wanted to be in a position to support myself. The quickest, easiest path seemed to be a teaching credential. I had a great craving to get back to school. I went to Cal State Sacramento and got the teaching credential. I got a masters degree as close to a linguistics degree as I could, then I realized that I had a stepping stone to a doctorate. I got accepted at Cal Berkeley and Stanford. I went to Stanford. I really loved it.

The girls were still in grade school when I got going. Their memories in childhood are of their mother as a scholar.

DF: The Los Angeles chapter of the Mattachine Society, the national homophile organization, asked you to give a speech in the early 1960’s. Your husband wasn’t pleased.

AB: No, he didn’t enjoy that. It was too close to home. It was near where we were living, for I was giving the speech in the Los Angeles area. He worried about that a lot. He worried about seeing our family name on one of my books. I wouldn’t have done that. He was a nice man, he meant well, but he didn’t know how to be anything but a Victorian father, even more than a husband. He was quite a lot older than me and I think it gave him authority. I was to follow his lead. He wanted everything to be storybook perfect. I tried to give him that for a great many years until the kids were out of college. That’s what brought my marriage to an end.

DF: While doing research on your career, I found the most breathless part was the hundreds of young women from cities and small towns who wrote you in the late 1950’s and early 1960’s, saying that your books offered them the hope that they were not alone, that they could live a life outside of a miserable closet, with hope for some kind of happiness.

AB: It’s a revelation and a very comforting feeling. It’s hard to believe in this age that young people still grow up, still sequestered enough, not to realize there are others that share their orientation. They are fearful. Often these are kids who have families that are extremely conservative. Many are extremely religious and want their children to follow in their path. A lot of them are in towns where there is little information available to them. It’s not that different from the 1950’s. You can’t go to the library and learn. You can go online, but what you find may be unappealing and frightening. You don’t know what to make of it and you don’t know where to turn in your locality. Maybe you’ve been madly in love with someone in your French class. Maybe you’ll be revealed and reviled in the halls of your school. You leave yourself vulnerable.

I got all these darling letters, hundreds of them. I discovered that Marijane had been getting them, too. The best-known person is the woman I wrote about before. It was a young woman who was going to kill herself. Her town had a river going through it. She was going to go on the bridge and jump. To steel herself, she stopped in a local drugstore and saw Odd Girl Out, which had just been published. She realized right away from the front cover and the title that the book might have something to say to her. She grabbed the book. You can read it rather quickly. She just gobbled it up. She sat on a bench and read through it. She said, “I went home and had dinner, instead of jumping off the bridge.” [Ann Bannon chokes up briefly.] I still can’t talk about it.

DF: Is that woman the novelist Katherine V. Forrest? [Editor’s note: Forrest herself is a famed lesbian writer, who has written 15 novels and mysteries, written many short stories and edited numerous anthologies. She was 17 or 18 when she read Bannon’s novel.]

AB: Yes, she is. (I’m sure I’m garbling her story a bit but you get the gist. Katherine tells it like the master storyteller she is!) Of course, we’ve long since met. She is one of the loveliest, brightest people I’ve ever known. I am overjoyed to have her in my life. She compiled the Lesbian Pulpbook. She’s paying it forward, helping other young women in her turn. I admire her.

DF: You stopped writing in 1962, but your books have a long tail. Arno Press republished your books in 1975, then the women from Naiad Press found you in 1983 to republish them again. This was the same time you were up for tenure at Cal State Sacramento.

AB: My god, I thought they might fire me. It turned out to be a very good experience. I swallowed hard and ‘fessed up in whatever essay I wrote applying for a full professorship.

Out of the woodwork came any number of supporters. The English department where I was housed had half a dozen very supportive faculty, mostly guys. Lavender flags also popped up in the PE department. It was a life affirmation I hadn’t had until that point. I had been a little afraid to republish the books. It turned out that the library already had the Arno Press edition of my books.

My books kept being published in various forms, the Quality Paperback Book Club copies and now the Naiad Press editions. I think they’ve become history books, to tell the truth.

DF: Women academics have been writing and teaching about your books.

AB: Yes, they have, and male professors, too. Many of the theses have been sent to me. They are well written.

Young women today are resistant to the idea that you couldn’t talk about your sexuality back then, that you couldn’t tell your parents, that you couldn’t live your life, that you couldn’t have a partner, much less a marriage partner. Why couldn’t you do that? Why didn’t you just link arms and protest?

We did, we marched, we did what we could, but it’s the old thing—you can’t fight City Hall. We laid the foundation. We provided a launching pad and a lot of people fell on their swords to make this happen.

DF: For young lesbian readers in the 1950’s, your books often acted as how-to manuals. How were they useful?

AB: Yes, in several ways. Linguistically, they provided the lexicon. This is how we talked, this is what we were talking about. This is what we were interested in, this is how we were negotiating the world through language.

There was the role playing. Where it appeared that the butch had all the power in a domestic partnership, it was the femme who had the power in the real world. She could pass, she could go out to work. She could get a job. Butches sometimes simply couldn’t. They were into the role to such a degree, they couldn’t pretend to be womanly or feminine.

What did you wear? The distinctions were more clear even than between boys and girls in high school. It was so important to claim that territory, to authenticate it in some way. What do I wear, what do I say? It was a presentation of self before that idea came into use. There was something about what you should do when you get to a bar. So few people would have that experience in the bars, they yearned for it, they wanted to know what to do, in case they were ever lucky enough to be in Chicago, New York, New Orleans or San Francisco. Where are the bars, how do I get there? It was pretty much social history in the making.

DF: There were warnings, too?

AB: There certainly were dangers. Even in these privileged enclaves, you couldn’t assume you’d be left unmolested. It’s a scary place. You shouldn’t be alone. I walked home late one night in the Village by myself. I was lucky nothing happened.

DF: Your books were not reviewed by the New York Times or any major newspapers. Was flying under the radar a good thing?

AB: This gave us freedom to write candidly about these matters. It helped that the country was slowly loosening up after World War II. The 1950’s were such a puritanical period, where they wanted women to be in the kitchen and they wanted the men to be manly. It was slowly easing. Even the Gathings Committee in Congress was being disbanded. This was the House Select Committee on Current Pornographic Materials, commonly known as the Gathings Committee, which was active in 1952 and ’53. Ezekiel Gathings from Arkansas was the chair. The grip they were having on morality was loosening. They were self-appointed moralists and they were going to tell the rest of us how to live our lives and what was acceptable. The big fear was that being gay was so seductive and so interesting that it would entice children.

We were pushing up against the constraints.

DF: What was your response to two women playwrights bringing your books to Off-Broadway as “The Beebo Brinker Chronicles” in 2007? You were finally reviewed in the Times!

(Poster for a production of "The Beebo Brinker Chronicles")

AB: I was absolutely delighted. Everyone was so kind. I owe Kate Ryan and Linda Chapman so much, and my current producer, Harriet Leve, more than words can say. Harriet has been trying to make a film or a TV series out of Beebo ever since the play came out. It’s been a long, long road, but she is an experienced Broadway producer and film-maker, and she recruited Lily Tomlin and Jane Wagner as our executive producers, who still believe in the project. I take heart that at first, nobody wanted “The Sopranos,” either, and it took 10 or 12 years for “Breaking Bad” to get to the screen.

DF: How do you view your most famous creation Beebo Brinker 60 years on? Do you see her, a no-nonsense Village butch, as a sexual ideal?

AB: No, Beebo is not an ideal. She is a child of her time, with serious flaws. But she was just so handsome and so much fun, I couldn’t let go of her.

DF: I have heard that you attended conventions on pulp paperbacks as a special guest. Was it a good experience for you? What kind of fans did you meet?

There used to be several paperback shows every year, in Los Angeles, New York, and elsewhere. The one major show still going strong is in Los Angeles/Glendale. They are a lot of fun, and collectors still treasure their special finds. But the appeal of the old paperbacks is fading. People are less aware of their history and the role they played in providing essential information on different lifestyles, from police work, to alternative sexualities, to exploring space, to the Old West. Often, this was information that was not available anywhere else. The cover art continues to appeal to a wide audience, and often draws readers into the stories. Fans who have found the books are often ardent supporters and wait in line to have their copies signed.

(Ann Bannon with her book covers at the Mazer Archives)

DF: We can’t believe everything on Wikipedia, but your page says that you are working on your memoirs. Is that true?

AB: No, but it was and I should. I wrote 150 pages and it was just dreck.

DF: You were divorced in the early 1980’s and finally started the life you wanted, surrounded by close gay and straight friends. You didn’t wind up with a life partner. Why?

AB: I’m perfectly happy. I’ve got six grandkids. The youngest is 15, the eldest, 31. And I have two wonderful daughters.

One of my daughters is very conservative. She is attracted to a fundamental version of the Catholic faith. She takes it in a very literal way. Her husband takes his Catholicism in a more intellectual way. She’s very emotional and it’s all about the Virgin Mary. That’s difficult. She wrote the local paper when they interviewed me, that it was a lamentable thing that I had written these books. She disowned that part of my life. But we love each other dearly and get along well. The younger daughter is more on my own wavelength intellectually.

I’m happy, I’m just fine with the way I am. If I felt a great lack or need, I’d take action. I’m in the latter part of my life, the 4th quarter, at the very least. I am good where I am, and grateful beyond words for what I have.

No comments:

Post a Comment