Christina Mitchell Diamante interviewed by telephone on May 8, 2021, in upstate New York.

In the early 1950’s a hipster named Alene Lee was frequenting the cafes and bars of Greenwich Village, an old working-class Italian neighborhood, which had been hit with an influx of writers and painters after World War II. Lee was a gorgeous, petite woman of African American and Native American descent.

At the age of 16, Lee had run away from her home on Staten Island, to escape a world of domestic violence and sexual abuse. Lee turned her back on a future of domestic servitude or a life on the streets. She sucked in the culture of Greenwich Village and Manhattan, going to classical music concerts and museums.

Though the Italian cafes and bars like the San Remo, the Minetta Tavern and Fugazzi’s took bohemian and hipster money and the neighborhood offered cheap apartments for the influx of new residents, there was a deep-seeded Italian animosity towards the wealthier invaders. Interracial couples on the street would be assaulted and black New Yorkers, visitors and residents alike, faced violence and discrimination in the Village.

Lee was mentored by the painter Virginia Admiral and eventually became friendly with the early Beats, including the poet Allen Ginsberg, William Burroughs and Gregory Corso.

In the summer of 1953, Lee had a love affair that lasted for several months with the novelist Jack Kerouac, who was intrigued by Lee’s beauty and her exotic African-American heritage. Kerouac considered Lee his soulmate.

After the couple broke up, on a three-day amphetamine binge, Kerouac wrote his novel The Subterraneans. He showed the book to Alene Lee a week later.

Lee was horrified. In an interview from the late 1980’s, Lee said, “These were not the times as I remember them.” She said, “It was like a little boy bringing a decapitated rat to me and saying, ‘Look, here’s a present for you.’”

The Subterraneans is set in San Francisco, following a group of young hipsters, and like many of Kerouac’s novels, the characters are thinly veiled versions of Kerouac’s friends, including Ginsberg, Corso, Burroughs and Lucien Carr. Alene Lee is portrayed as a young woman named Mardou Fox, prone to mental breakdowns.

The novel was finally published in 1958, after the success of On the Road in 1957.

Even by the standards of 1953, The Subterraneans is a horribly racist and misogynistic novel. After sex, the Kerouac character is disgusted at the sleeping Mardou’s frizzy hair. He has her character speak in a naive style and laments that he could never take Mardou to meet his famously racist mother. The Ginsberg character loudly claims that sex with Mardou broke his penis, which is based on Ginsberg’s real-life, offensive comments.

The Subterraneans had the longtail effect of making Alene Lee’s life difficult in the Village, where she lived for the rest of her life. For decades, strange men on the street would make sexual overtures towards her as Mardou Fox. Lee saw the explicit sexual content in the novel of their real-life intimate moments as a betrayal by Kerouac.

In 1957, Lee had an affair with the Beat entrepreneur John Mitchell, who founded the great Village coffee houses Café Le Figaro and The Gaslight, where Beat poetry and folk music exploded. Their daughter Christina was born that year. John Mitchell eventually fled New York for Morocco when he was told by the Italian Mob that if he didn’t leave the city, they were going to kill him.

In the early 1960’s, Alene Lee and her daughter Christina Mitchell, then five, moved into Lucien Carr’s small rented house on Horatio Street after the end of his first marriage, that had produced three sons. Carr had committed the original sin of the Beats by murdering his ex-Scoutmaster David Kammerer up at Columbia University in 1944. He used a “gay panic” defense to only serve two years in prison for manslaughter

The charismatic Carr was an editor at UPI and a hopeless, violent drunk. The 11 years Christina Mitchell spent on Horatio Street were a harrowing story of domestic violence, where Carr beat Lee almost every day. At one point, he knocked out Lee’s tooth on the sidewalk in front of the house, which forced the police to arrest him. Lee did not press charges.

Most nights were full of screaming fights and the house had no glasses or plates because they were routinely shattered against the wall. After 11 years, the mother and daughter were told to leave when Carr, then in his late 40’s, became involved with a teenage girl, who would become his second wife.

Alene Lee died of lung cancer in 1991 at a Manhattan hospital. She was 60. Allen Ginsberg, for all his flaws, was a loyal friend, visiting her at the hospital as she lay dying.

Lucien Carr eventually moved to Washington, DC, to run news operations for UPI. He retired in 1993 and died in Washington at 79, in 2005.

I found Christina Mitchell Diamante living in upstate New York. In the 1990’s, she carried out extensive research and writing on the life of her mother Alene Lee, when she went to college at SUNY Oneanta. She produced a 238-page history of her mother and their extended family.

Diamante give me an excellent, often wry interview, where she discussed her mother’s family history and Lee’s early days in the Village, as well as her mother’s harsh reaction over her unfair portrayal in The Subterraneans. She also detailed the 11 years she and her mother lived with Lucien Carr on Horatio Street, and the violence that was an everyday occurrence.

In our epic interview, Diamante filled in a lot of details on three of the most underreported figures from the 1950’s bohemian Greenwich Village: Alene Lee, who often fought off Kerouac’s biographers to protect her privacy; her father, the carpenter and artist John Mitchell, who disappeared for many years after he was run out of the Village by corrupt cops and the Mob, and Lucien Carr, whose family and supporters have worked to cover up his violent alcohol-soaked behavior in the 1960’s and 1970’s.

Diamante also was able to discuss the corrosive effects that trauma and racism have had on three generations of her family, including her grandmother, her mother and herself.

Christina Mitchell Diamante was raised in Greenwich Village. She ran a successful proofreading business in the city before she moved up to the Albany area in 1991, to raise her children. She still lives in upstate New York. We spoke by telephone.

DYLAN FOLEY: When we spoke two weeks ago to arrange our interview, I realized that I did not want to re-traumatize you with any of my questions.

CHRISTINA MITCHELL DIAMANTE: I think you should feel free to ask any questions you want to ask. It is less traumatizing to answer people’s questions. It is the difference between talking to someone about your parents and driving to the cemetery and visiting the grave. Driving to the graveyard was what my research as like, visiting the grave, digging up the grave and looking at the dead body. It is writing about my mother, researching and remembering her, and reading her writing that is traumatizing.

COPD was what my father died of. I don’t know if you were aware of my father. My father John Mitchell actually started the reading of poetry in the Village cafes at the time. He actually was a carpenter, a builder and an artistic guy. He started the Figaro, the Bistro and the Gaslight. And also the Fat Black Pussycat. It is still there on Minetta Lane, or it was there 15 years ago. There were stained glass windows that he put in by hand. I have a signed book from Peter, Paul and Mary, from Peter or Paul, the one that is still alive, who was doing a PBS special. He said, “Your father was a mensch because he would put a jar out…certain people got their first gigs with him.” The only pay they got was a jar that my father put out. He gave them the money. That’s the nicest thing I can say about my father.

My father disappeared because he organized a march to City Hall [by café owners]. There’s a picture with him of Mike Wallace, the CBS news reporter. There were signs by the business owners. This was pre-Serpico. “We can’t afford payoffs to the Mob, the Fire Department and the Police Department.” He was a very outspoken person. He was literally a small-business person, who could not afford to pay these bribes. Shortly after that, his restaurant was firebombed. He was sent a message by the Mob that he could either leave the country or he could die. He was going to leave one way or the other, so that was a clear and direct message, the firebombing and the person who came and delivered the message. He knew it was no joke. He went to Morocco and lived there for several years. He created the same three restaurants—the Figaro, the Gaslight and the Bistro, then he moved from there to Spain, where he recreated one of those restaurants under the same name. He also produced a half-sister of mine. My father had extensive tapes, and my sister may have access to them. They were supposed to be given to me, but they were left with a young man in Arizona that my father was fond of. My father had an extensive history of the Village and interviews with some great poets. He also published a book of poetry from the poetry readings in one of his restaurants. I believe it was the Gaslight.

DF: Let us start with your mother. How did Alene Lee’s family wind up in Staten Island?

CD: My grandmother Mamie was born in Greensboro, North Carolina, and was an orphan around the time of the great 1918 flu epidemic. She was raised by a white family because she lost both of her parents. This was around 1918 in the Jim Crow south. She wasn’t raised as a child, she was raised as a maid. She was a live-in maid for this family because her parents were deceased. Mamie reported having visits from her uncles, who were Cherokee Indians, who had not left in the Great Migration. They would come down and visit her on horseback, from wherever they were living in the hills.

I have DNA evidence that we are Native Americans, but Native Americans can’t always be picked up by tribes because of the interracial mixing between whites and blacks. Mine comes through as Siberian, which would have been the first wave of Native Americans. Mamie went on to marry a World War I veteran and she had two children with him, living in Washington, D.C. He was shellshocked and was violent.

Mamie gave birth to my mother, apparently with another man. She and her two eldest daughters and my mother apparently flew by plane to New York and settled in Staten Island. The interesting thing that my mother and other relatives pointed out is that poor black folks in 1930 did not get on planes to go anywhere. She was married or divorced at that point. She didn’t have a career or any money. When she moved to Staten Island, she had a whole lifetime of work as a domestic worker. Somehow, she had the money to get herself and her three children on a plane to New York. Nobody quite knew what happened there. The only relative who knew the story refused to speak about it.

My Aunt Russie was in the piece I wrote called “Three Sisters.” At the time, I wanted to understand the family history, but it was too painful for her. Something horrible happened. My mother was said to be the half-sister of the two older sisters. Her father is said to be a man named Garis. The other sisters’ name was Lee. My mother’s name was Alene Garis. Her first name was originally Aileen. She changed her name to Alene when she moved to New York City. She was trying to reinvent herself.

The older sister Aunt Russie moved to Washington, D.C., where she and her husband became middle-class black people, who owned a beautiful house in a white neighborhood and they owned a chicken restaurant, which ostensibly was their source of income, but they were numbers runners for the Mob. When I stayed with them, I would go into their bedroom and I would see them counting giant stacks of money. I never knew what was going on, but it was odd. One evening, someone rang the bell. Aunt Russie and Uncle Eulie looked at each other and said “We are not expecting anyone.” Uncle Eulie went and got a gun and went downstairs to the front door. Apparently, it wasn’t someone intent on robbing them, so everything ended well. That’s the mobster story. Years later, she turned state’s evidence after Uncle Eulie died and the law closed in on her. She testified against someone in the Mob, but he must have been a lowly person, because she wasn’t killed. She then left D.C.

My mother’s other sister Catherine had a troubled life. She lived most of her life in Staten Island and had 12 children through two marriages. She moved to New Jersey and died of anaphylactic shock. She developed pneumonia. They gave her penicillin, but they didn’t know she was allergic and she died.

Everyone in my mother’s family, excluding one sister, died before the age of 60.

My mother lived on Staten Island until she was 16. She had a very contentious relationship with her mother. She had been sent out to live with a foster family, an Aunt Janie. She hadn’t lived with her mother for several years. Her mother had had a fourth child, Aunt Esther, and she was the favorite child. It was kind of like Sophie’s choice—she could only afford to take care of herself and the baby. She decided to send my mother out. Alene was sent to live with Aunt Janie, where she was the effective live-in maid. My mother didn’t mind—there were three meals a day and everything was neat and clean and orderly. It was a father, mother and son, an actual family. She ended up doing a lot of housework, but it was a stable environment. She was raped by the son of the family. She didn’t see it as rape. She saw him as the only person who had ever shown her any affection. I only qualified it as rape because of the age and power dynamic and because she wasn’t asking for sex. She wasn’t even a teenager. Shortly after that, she was sent to live back with her mother.

There were numerous incidents and my mother was on the verge of going the wrong way. I know some of the things she did through her writing. She told her mother that she was going to night school in Manhattan. It was near the Con Ed building on 17th Street. There was a high school that offered night classes. She decided she wanted to get out of the home. She was 16 and had taken a train trip to the Village on one of the days she was playing hooky. I wrote this or maybe my mother did… she got out of the subway and the first thing she saw was Balducci’s. She saw people walking around in brightly colored scarves. She liked the niceness of the area. Niceness is not a word my mother would use. She said, “I am going to live here.”

She told her mother a story and moved to Manhattan and wound up living in the YMCA for girls, off Grammercy Park. She developed an interest in classical music and art, and started going to see these things in the city with her friends from the YMCA. They spent a lot of time in coffee shops, and subsequently in bars. This is how she possibly got involved with “the Beats.”

My mother ran away from home at 16. She lied to her mother and was not going to typing/secretarial school. She had not graduated from high school and never did. She wanted to have a different life than the life she was having then on Staten Island. A friend of hers, a very close friend of hers in the Caribbean community, had been shot and killed by her husband. Her mom had been friends with her. It impacted her and she had to leave, she had to get out. That is the salient incident that caused her to leave and go to Manhattan.

DF: How did she support herself at first?

CD: She was supposed to go to a vocational school for typing. She may have learned basic typing in high school. She ended up meeting Victoria Admiral, the mother of Robert DeNiro, the actor. His mother was a painter of an earlier generation, not a Beat. She and her husband Robert DeNiro Sr. where painters belonging to some abstract school. She was one of the first women to have a painting exhibit at the Museum of Modern Art.

At the time she met my mother, somewhere between 1946 and 1950, Virginia had given up her art and was divorced from Robert DeNiro Sr. She was raising her son on her own and had an apartment on 14th Street, off 8th Avenue. She had a typing business on 8th Avenue. My mother began typing for her. Virginia was a left-wing Trotskyite, who felt a connection with my mother. She later said, “I loved your mother, she reminded me of my mother,” who had been mentally ill and had serious mental breakdowns. She and my mother became friends. In my mother’s life, Virginia was her best friend.

My mother was able to do typing work for Virginia. Back then, anyone who needed a paper typed would go to a typing service. She encouraged Alene to start her own typing service. Anytime Virginia got a referral for a dissertation, she would send it to my mother. My mother was supporting herself by typing. She did this independently until I was 5. At the point I was 5, she met Lucien. Shortly after the breakup of Lucien’s marriage to Cessa, Caleb’s mother, my mother moved me and her to Lucien’s townhouse on Horatio Street. At that point, my mother kept having to support herself. Lucien was an editor at United Press International. His money was his money, her money was her money. They didn’t share finances. My mother had to support me and her.

My mother only agreed to have me because Virginia and Virginia’s therapist had said to my mother, “You’ve had so many abortions…it is clear that you want to have a child and we’d think you’d be a very good mother.” My mother wasn’t living her life in the typical way of getting ahead. My mother was self-educating herself. She was spending time in restaurants and bars, interacting with literary people and reading a wide variety of books to do with the dissertations and theses that she was typing. This made her a very well-read person. She just didn’t type the papers, she had to create the footnotes. She had to go into the books and read what page she was on. She was a voracious reader and essentially was their copy editor. She was making sure that all the information they were quoting was correct. She was learning a lot at the same time.

The entire time we lived with Lucien, she was paying her portion of the rent.

DF: Your mother was a rebel—she ran away to build her own life, she chose her sexual partners. She was not a 1950’s housewife. Where did this rebellious streak come from?

CD: That’s an interesting question that only my mother could answer. In fact, everything I tell you is how I suppose things are, for the truth is relative and it depends on the standpoint or angle that you are looking at things. If I were trying to determine this on my own, I could point to several factors and you or whoever could determine where it came from.

My mother, like my father John Mitchell and Lucien, was…I don’t want to use the word narcissistic because that would imply someone who was trying to use things to their advantage. She was a very strong-willed person. I don’t know if I would call it a rebellious streak. It was more of an air of defiance. She walked a fine line during that time in Staten Island. She might have been what you call a street kid, who could have gone into dark places. She saved herself by getting away from there. Her life there was going to be the lives of what her sisters had. Her experience in the community she was brought up in, the black community, her experience was being given away by her mother, raped by the son of her new family and having her best friend being shot by her husband made her determined to leave. There was nothing for her [Alene] to want to be there for.

She came to Manhattan and tried to learn as much as she could. She wanted to write. She wasn’t a narcissist. She didn’t have the self involvement the way that Kerouac had [in 1953] when he jumped in the cab with Gore Vidal. The other side of the story is that he left my mother standing there on the street with no way to get home. He could do that because he was on a mission to experience as much of life as he could and write it down and to create these books, these great works of art. My mother did not have the narcissistic energy. She was trying to survive and to find little ways to thrive where she could.

I believe my mother felt much of her life like she was hunted, like she was being pursued by many men, because she was, in her day, very beautiful and what white people would call exotic. She’s getting that kind of feedback on one level and on another level she’s completely unemployable, she doesn’t have a high school degree. She was just struggling to survive. She writes that she couldn’t really figure out how to function in this world. She hadn’t really figured out she was supposed to be here.

I once asked my mother what does prejudice look like. I am a light-skinned person and a DNA test showed that I am only 22 percent black, which means my mother wasn’t fully black either or fully Indian.

If you extrapolate amounts and double them, my mother would have been about 44 percent black, about 16 percent Native American or Siberian, then the remainder being white. She was a brown-skinned person. She did experience prejudice. I didn’t. I looked white and only people from the South, or people who really cared, especially a lot of Jewish people, knew that I was black because they saw the frizzy hair as an indicator. A lot of people weren’t looking for that as an indicator. I might have been Irish or Jewish.

I asked her what prejudice is like. She said, it’s like you are walking down the street…people in those days didn’t really look at each other. We looked at a spot on the person’s forehead. You didn’t meet eyes with people, for that was a dangerous proposition. She said if a person met her eyes, there was this initial blank look, and then their eyes would start to narrow, and you could see the fear and suspicion in their eyes.

It was palpable. She said if you were in the unfortunate position where you had to talk to them, whether it was a person in a store, from that point on, their attitude was that she was an inferior, stupid person. Her basic mode of survival was no, I am smarter than you. No, I am actually smarter. She became this person who had to continually prove to other people that she was a worthy human being, an intelligent human being, and a human being that they had no right to treat so dismissively.

DF: Was Aline Lee in psychoanalysis?

CD: Yes, she was. I don’t know with whom, but the doctor was the head of the psychiatric ward at Bellevue. She had been sent to Bellevue several times, along with her sisters. She suffered from some mental illness, which as far as I know was never diagnosed. She clearly did have some mental illness.

Some people have suggested that my mother was a drug addict. Let me tell you something, you can’t live with someone in a house for your entire childhood up to 16, when I left home, without seeing evidence of drug use. What I did see in the house on Horatio Street…there was never any liquor in our house. In the 11 years I was living on Horatio Street, I was sent on a nightly run to get a fifth of vodka. In those days, you sent your kid around the corner to the liquor store. I think the guy’s name was Larry. I would pick up a fifth of vodka, basically for Lucien, but my mother drank with Lucien. I saw a lot of liquor and I know, because I bought it for them. This is from age 6. I saw Lucien take barbiturates, bennies, at night, and some form of amphetamine in the morning. These were all prescribed. They were in prescription bottles. He was being treated for whatever mental illness he had. We didn’t call them amphetamines. We called them by the name of whatever prescription drug they were. To top it off, he’d have a fifth of vodka, or however many drinks they’d have if they were out. They went out to bars. I call my mother a social alcoholic, to be with Lucien. Lucien was a drinker. She and Lucien drank.

I want to say from the beginning, I loved Lucien and Alene. They were seriously flawed individuals. I do not know what their motivations were for what they did.

During that period, I did see my mother have several breakdowns, one of which was very upsetting, where she had a convulsion. I put her in the bath and said, “Mommy, let’s give you a bath.” She had convulsions and had to be taken to the hospital. I don’t know what it was.

I can’t say that my mother didn’t ever take any drugs, but she was not a drug addict or a drug user. She may have done them recreationally, as probably all of those people did. That was what I wanted to clarify.

DF: How did your mother fall in with the Beats?

CD: Before the summer of 1953, she had already known Allen. She never told me how she met Allen, nor did Allen tell me. He was very obsessed with telling me another story. I recorded an interview with him and he went on and on about how he thought my mother broke his penis.

DF: Wasn’t Allen Ginsberg mostly sleeping with boys by then?

CD: This precedes him ever sleeping with men. All I know is that my mother and Allen were friends, who became lovers, and they had a sexual experience that was very bad for him, where he said that she broke his penis. At any rate, Allen had said, and I think it is in The Subterraneans, that he couldn’t be involved with a black girl.

He told Kerouac that my mother might be someone interesting to meet. I don’t know what they exact words were. I don’t think he was trying to pimp her out or anything. I think they were all a very incestuous group. I have a picture and it’s in Allen’s photo archive, and it is of Alene and Jack sitting on a couch in Allen’s apartment. I think she met Jack at Allen’s. It was not a month-long romance as he wrote. They were involved for several months. They had to know each other for several months before they became involved.

Even after the break up, they knew each other, but were not friendly. She was infuriated when he presented the book to her. He created verbiage that she never used. She never said things like, “Oh, baby, baby.” He asked her if she wanted anything changed in the book, and she said “Please get rid of that ‘baby’ stuff. I don’t talk that way.” It was his book and to some extent, it was fictionalized.

DF: Your mother’s strong personality came through in the oral history, Jack’s Book and The Subterraneans. She makes fun of Jack for being tied to his mother’s apron strings.

CD: She wrote about Jack and I have her interviews with Gerald Nicosia and with Barry Gifford and Lawrence Lee. I have the typewritten manuscripts, but not the tapes.

My mother wrote about that period of time, but as a child, I didn’t really know anything about her life, except what happened in the house on Horatio Street. As an adult, I went through her papers and learned a lot more.

DF: Did she talk about 1953 and being involved with Kerouac?

CD: For her, being involved with Kerouac made her a kind of target. She would walk down the street in Greenwich Village where we lived and total strangers would walk up; to her and say “I hear you are Mardou.” In the novel, he’s talking about sexual experiences. What kind of person in New York City stops a stranger to talk about their sexual experiences with a writer? For her, she spent the rest of her life trying to stay out of the spotlight. She was not the kind of person who said, “Oh, I met So and So today.” She was around Robert DeNiro and other celebrities. Harry Belafonte once asked her out. I only found out about this in her writing.

If she did talk about people, it was establishing with another person that she was not who they thought she was. “This is what you see, but I am a person with a wide variety of experiences.” She was not a namedropper.

She didn’t discuss anything about her childhood, her relationships at all, until many years later. She did tell me one thing about Lucien, Jack Kerouac and the man that Lucien killed, David Kammerer.

There were many bad things about these people and many things about my father that were horrible, but she didn’t want me to hear these kind of things. The ethic that she seemingly lived by was to put these experiences behind you. You have to keep moving. Einstein said, keep your equilibrium and move forward. That would encapsulate my mother’s m.o. She was often on the verge of a nervous breakdown. To dwell on these things could have knocked her off. She rarely talked about the past.

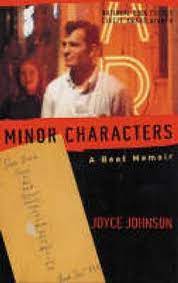

DF: You make an off-camera appearance in 1957 as a crying baby when Joyce Johnson and Jack Kerouac visited Alene Lee in Johnson’s memoir Minor Characters. Your mother had just had you after her affair with John Mitchell. She was dismissive of Kerouac’s visit.

CD: I want to comment on something you said. My mother was very angry and disappointed in Kerouac. She didn’t slough off their relationship. What he did really hurt her. Subsequently, he writes about the disgust he feels when he sees her sleeping, her nappy hair and the sex. These things were real insults to her. That was not something you did. In 1950’s-speak, you do not kiss and tell. This was a real invasion of her privacy. It was almost as if you knew someone who worked for the Enquirer. Then they put you in the Enquirer. Her overwhelming feeling about Jack was here was someone I loved who betrayed me. It’s encapsulated in that scene, which you call comic but actually was very hurtful to her, where he jumps into the cab with Vidal, leaving her in the street without a penny to get home. This was what he was going to do. He later laughed it off, she sloughed it aside—“We were just playacting at a relationship.” She wasn’t going to waste her time if she didn’t love you. She wasn’t into random sex. She would have sex with people she loved. Very often, Dylan, frankly women have sex with men they love, even if they are not interested in sex. For men, it was a great exotic sexual experience. I don’t think she really understood what they were doing. Lucien, Jack and Allen all had this Rimbaud-style concept that you must deprave yourself and become depraved to be really great writers. Anything that was odd or unusual was something they had to delve into. Kerouac was delving into my mother’s life without any consideration that she was a real human being and a vulnerable human being trying to find the normal things that other human being find with each other—connection, security, love. She never framed herself that way. She had chosen a life where she was going to be doing what she wanted to do and not in the confines of anyone else’s control, with the exception of being truly romantically involved with Lucien.

My mother had romantic feelings for Jack. She loved him and she loved Lucien for life. She really became a subordinate character in her relationship with my father John Mitchell. I have no idea how they met. I assume it was in one of his coffee shops. She loved him very deeply, too, and was very, very angry when they had a sustained relationship, she became pregnant and her friends convinced her not to have an abortion, i.e. with me. John Mitchell had sex with anything that moved, including men and women. I don’t know if he was involved with men at this point, but he did have multiple relationships with women at this time.

He had lost his first-born son John, my brother, shortly after World War II, when his then wife moved to California and took Baby John with her. My father drove to California, stole Baby John, put him in an orange crate and drove across the country with him. My father was subsequently forced to give him up. When that happened, something broke in John and he treated everything in life like he had no respect for others. He had a very narcissistic personality. He felt that we were all on the same playing field.

One memorable thing about my father was when he had the coffee shop, the Fat Black Pussycat. I was about two. My mother had brought me there. I was in pajamas and barefoot. My mother asked him if we could have some food, because it was restaurant. He brought a bowl of ice cream. My mother flipped out and started attacking him, probably throwing dishes. He tied her to a pole in the middle of the restaurant and called the police. I was put outside. My recollection was that there were some sort of stairs and stained-glass windows. I was standing there barefoot on Minetta Lane and my mother was taken away from the police. I was taken away by a friend of my mother’s named Lenny Rubin and spent the night with him until my mother was bailed out of jail.

All I know of my mother’s relationship with my father is that he loved her very much but did not want any committed relationships. He just moved from woman to woman, until he was told to leave the country or be killed.

DF: Did your father John Mitchell uphold any emotional or financial responsibilities with you?

CD: Absolutely none. I never spoke to him again until I was 12 and going to the Downtown Community School on 10th Street. My mother never said a bad word about him. She never said anything about him, except that she loved him and he was living in another country.

DF: Did you see your father after you were 12?

CD: He had been given permission by the Mob to come back. They said “You can come back, but you must not start a restaurant or a bar.” He came back and worked with his friend who owned Edison Lighting, which was in the city, under the midtown bridge, I think, where the horses were kept.

He visited me at school. He was wearing a purple wig. He gave me some trinkets that he was thinking of importing from Morocco. These were little tinny toys you pressed on. Even from the perspective of a Beatnik child, I knew these would break.

I only has a relationship with my father after I moved to upstate New York. We had been talking and he had been diagnosed with emphysema and COPD. I began talking to him on a regular basis. I had been comforting him because he was scared and alone. I was scared and alone, for my husband was in the city, running our business. I was living upstate with my son. I developed a relationship with him, more like cousins or peers. I didn’t have judgment towards him. We saw him two times after that when my husband, family and I flew out to Arizona to see him, when he was dying.

My father had moved out to Arizona a good 10 or 15 years before he died. He called it a ranch, but I called it a trailer with a dirthole. He had several houses and had an estate of a million dollars. He was a very good businessman. He left all of all of his money to my half-sister, who lives in Majorca, Spain, on the condition that she’d take care of his nine dogs. When we went to his house, he was cooking nine steaks for his dogs. Dogs were his people. He loved dogs. Lucien also had some of his closest relationships with dogs.

DF: Back to The Subterraneans…how old were you when you read the book?

CD: My mother had asked me as a child never to read that book. I honored her request until her death. It was when I moved upstate to Oneanta, when we did “The Children of the Beats” article. [Editors note: The article was in the New York Times, written by another Beat scion, Joyce Johnson’s son Nathaniel Pinchbeck.] I was at that point that I got a grant from the college to write about my mother, I read the book. We were talking about the 1990’s. I was better educated at that point. I had gone back to college.

I had not gone to college after graduating from Stuyvesant High School. I had run away and joined the Moonies. It was a rather unfortunate waste of my life. I was essentially running away from home. I wanted to be someplace where they fed you three meals a day. We thought we were saving the world. It was like the Peace Corps, but unfortunately it wasn’t the Peace Corps. I knew nothing about religion and knowing nothing about religion meant that they could sell me any pile of crap. I didn’t care…if you want to say he’s [Reverend Moon] the Messiah, that’s okay, as long as we are saving the world. What it really meant was friends, family and food, and a place where arguing, screaming and fighting weren’t always going on. Then it was five years later.

I don’t hate either Lucien or Alene now. I am just disappointed that they couldn’t do better. They never asked me what college do you want to go to. If they asked me, I wouldn’t have wound up in the Moonies for five years. The strain of living with someone going through a breakdown can be very difficult. I know that in their own way, they were both mentally ill.

DF: What was your response to reading the book?

CD: I was horrified. I was truly hurt for my mother, that someone who had said they loved her would write a book that said they felt disgust seeing you lying in bed because of your hair. The things he said—“I couldn’t bring a black girl home to my mother.” A man said that to me, too. I know how horrible it would be for a man to say, “My mother would disown me if I brought you home.” I was horrified. I began to see who these people, who everybody loved and praised, who they were from the point of view of how they treated people like my mother, people who were disempowered, the exotic other. I don’t think these people really saw what they were doing to the women in their lives.

Corso…one of the reasons my mother didn’t want to discuss that period was because of Gregory Corso. She said he was a dangerous and violent person who she was afraid of and she couldn’t say anything about that period because she was afraid of Corso. He must have done something or knew something about her character to make her feel that way.

Honestly speaking, after 11 years of living with Lucien, with his beating my mother on an almost daily basis…she had scars on her face and one tooth knocked out right in front of me, in front of the house of Horatio Street, watching blood drip down from her mouth to the sidewalk, having the police come and being carried off to the 9th Precinct, maybe watching him in a cage, standing in my bare feet and pajamas again, and all of this, years of this, had become normalized in my mind, because that was all there was. You grow up in a concentration camp and if things continue this way, you don’t think you are in a concentration camp. That’s just where you live. Is it Socrates or Plato, who wrote the parable of the cave? You don’t know you are in a cave until you get out of the cave. Psychologically, it took a long time for me.

These are people the culture makes into heroes, who were so enamored of them. I hesitate to talk to you, because I sound like an angry person, but as an older person, I realize that most of these people were mentally ill, undiagnosed. They were nuts. They were not trying to be but the results were kind of evil.

DF: The more I study the personal history of the Beats, the less I like them. I don’t know if Lucien Carr emotionally survived the murder he committed in 1944.

CD: It was before Columbia. David Kammerer had been hired by Lucien’s mom. They travelled round the country together. It was a whole period of this person maybe grooming, maybe intentionally falling in love with Lucien. I don’t know all that he went through.

I don’t really know Kerouac, so my assessment is based on what he wrote about my mother and what effect that had on her life. I do want to tell you something about Lucien from the beginning. I loved Lucien an I loved Alene. I loved him as you love a father. They were seriously flawed individuals. I do not know what their motivations were for what they did.

I spent the last five or six years of our 11 years with Lucien saying to my mother, why don’t we leave? Her saying to me in response, “You need a father figure.” He was my father figure. I was told to call him my stepfather. I have fond, fond memories of Lucien and doing specific things. With him, that were really fun and showed his childlike nature. He took me to see Mary Poppins, and when we were done with the movie, we skipped down Hudson Street, and skipped and twirled the way Mary Poppins did. He swung me in the air and was singing the songs.

Drinking doesn’t make you a different person. It just shows the sides that others can’t see. You can’t excuse what people do when they are drinking, because that’s part of their character. They are making a choice.

Lucien took me to see “Love Story.” Tears were pouring down his face. I sat there stone-faced and emotionless, because my experience with love was “Hey, you beat my mother every night. We live in a house where glasses and plates don’t exist because you’ve broken them all. We live in a house where I can’t sleep because the fighting goes on ‘til 3 or 4 in the morning.” I wasn’t angry with him. This was the way it was.

I became emotionally catatonic for long periods of time. To this day, I do not trust any authority figure at all. My experience is that they are all self interested and dangerous and you need to be wary of them.

At the same time, what happened to Lucien did not excuse his behavior. I loved him and I am sorry to his sons Caleb, Ethan and Simon, but Lucien began grooming me at about age 12. I don’t think he went into it with a concrete plan, but I remember him sitting me down in a chair on Horatio Street. “You know, your mother is very jealous of you, right now,” he said. “You are at the age when men are going to start looking at you as the person they want, not your mother.” I remember looking at him and thinking, what the hell are you talking about? I am not even interested in men. Men are going to want me? The last thing I wanted was to have anything to do with men. The context of this conversation, I had no freaking idea what he was talking about.

Keep in mind, I had spent many hours in their bedroom, where they had full-wall mirrors for some purpose. I later found out what they were for.

As a child, Lucien had gotten me interested in flaking the dandruff off his head with a comb. I spent hours doing this. It was very fun flaking off the dandruff, trying to get to the end. Different parts of his head were meant to be different continents. “I’m in Africa now!” It was all very innocent from my perspective, but as an adult, I asked myself what kind of an adult has a half-naked child lying on top of them, and why are there pornographic books on your bookshelf, when the only thing to do in that house was to watch TV and the TV was in their room. So I watched TV and went through the books on the shelves.

Subsequent to the conversation in that chair when I was 12, Lucien told me that, “I’m leaving your mother and you because I have found a person who loved me more.” That other person who loved him more was, like me, who was a teenager. That person was Sheila Johnson, who unfortunately had her back broken when Lucien took her on a drunken trip through snowy roads of upstate New York to Allen Ginsberg’s farm in Cherry Valley, where he was slugging down vodka as he drove, which he did on our trips to Cherry Valley, when I went as a child. He ran into a tree and broke his leg She was in a full body cast for some period of time. Sheila was the adopted daughter of Lucien’s reporter friends in Washington, D.C. The only way out of this, from his point of view was to marry her, so he did. He took responsibility for what he did to Sheila.

His reaction to my mother and I was “You have to leave the house now,” the house we had lived in for 11 years. “I’m going to living here with the new love of my life.” I loved Lucien but what he did was horribly cruel and vicious.

DF: I hope that Lucien didn’t succeed in molesting you.

CD: No, he didn’t. There was one time when I was in the shower. We had a shower under the stairs, which had a toilet and a stand-up shower. This is rather personal. I was 13 or 14 years old and was learning how to do handstands in a little gymnastics unit at school. I was doing a handstand in the shower and the shower was on. When I got out of the shower, Lucien said to me, “This is a practical way to clean things you can’t reach.” I was wrapped in a towel. “Were you masturbating in there?” This is not something you say. I am sorry that Ethan, Caleb and Simon may have to hear this. First of all, they may not believe me. Second, and most importantly, I’ve never told anyone this, except a close personal friend, because I did not want to hurt Lucien’s kids. I didn’t want them to hear anything more that was bad about him.

I don’t really feel much about it now. I am not in the mode of reliving. I am more in the mode of retelling. I had to think long and hard before I told you this. My mother had never said anything bad about my father, Lucien or Jack. It was my mother’s ethic never to say anything bad about people, even if they did bad things.

It is fine to praise the artistic work, but you can’t turn people into heroes if they are deeply flawed. They have put themselves in the public spotlight, and as a result, it is only fair because there are other people who are survivors of abuse, who have to work through this.

I hate to do anything that would hurt “the boys,” as we called them. These men—Kerouac, Ginsberg and Lucien could be very kind, thoughtful and intellectual, but also completely thoughtless. Their process of engaging in depravity didn’t take into account that they dragged other people into this depravity.

In Lucien’s bookshelves, there were books that depicted incestuous relationships between father, mothers, brothers and sisters. I read all of them. It warped your concept of what relationships were, being brought up in a home where they beat each other up, going to police stations, going to Bellevue…This is how it is everyone… “You are a child of the Beats, this is wonderful. Isn’t it amazing?”

DF: Your mother was fiercely protective of her anonymity, especially with Kerouac’s first biographer Ann Charters. What happened?

CD: Ann Charters was angry at my mother. She wanted information and my mother shut her down. My mother always collaborated with Lucien, even after their breakup. The m.o. was to protect Lucien. Don’t say anything that could hurt Lucien or his family. Lucien was on lifetime parole. Even after he knocked my mother’ tooth out, and we were all dragged to the precinct and my mother was supposed to press charges, she ultimately dropped them. If he had been convicted of assaulting my mother, in such an obvious way that the police could not ignore it, he would have gone back to prison. In addition, his was such a psychological trauma for him. He was an editor at UPI. His goal was to stay out of the news.

My mother loved Lucien until the day she died. Her loyalty to him was such that her desire for privacy over Jack and that book was very strong. She understood how Lucien felt. She only told writers what she could tell them without hurting Lucien. In a sense, she did the same with Kerouac and Ginsberg. She didn’t tell anyone the depth of depravity that had occurred.

When you are a victim of abuse, you inculcate or incorporate guilt, and because you are part of it, you are a participant. In your own mind these are things you did, not just thing that happened to you. And that’s true. My mother would say that you just don’t talk about it. It was an old-world way of looking at things. In this day and age, people don’t understand, because they all have their sex tapes.

I remember clearly my mother having phone conversations how they were going to handle this or that author. They were trying to control what would go into the biographies.

DF: In the Kerouac oral history Jack’s Book, your mother, under a pseudonym, seemed to be able to speak honestly.

CD: Honesty doesn’t mean the whole truth. Nobody gets the whole truth. Just because somebody asks, nobody has a right to your truth.

DF: You wrote that particularly moving “Barefoot Beat” essay about your mother on the website Beatdom in 2010. Some of the comments were savage, including a broken-English attack by a Swedish man.

CD: I didn’t think it was a Swedish person. I think it was somebody with a vested interest. I felt it was someone who knew Lucien. They weren’t questions, they were statements: “Your mother was just a drug addict.” They were designed to hurt. Where would you come up with that, my mother was a drug addict? Who would have that information?

There was the incident that Jack describes that did happen to my mother as Jack described it. A bennie was slipped into her drink. She describes it as something she didn’t plan on, but she did wind up walking around naked in Greenwich Village and subsequently going to Bellevue.

As a child, I developed an eagle-eye ability to tell when my mother had had even a sip of liquor. She had an immediate reaction. You could see how her eyes set and the muscles in her face went when she had a drink.

You can tell when someone is on a drug trip. I never saw her taking drugs.

DF: Did your mother and you have a business together?

CD: I started a proofreading business when I moved back to the city. I started working at a company my godmother Virginia’s nephew was working for. It was a proofreading company. Virginia had said to me, “It’s obvious you are unemployable.” It’s true. My mother and I were very combative people. We would have reactive explosions, if someone said something that was rude or hostile. It was going to be an aggressive response. You become unemployable.

I remember once as a child sitting in the staircase at the house on Horatio Street, crying early on. Lucien came up the stairs and says, “What’s wrong Christ Child?” his nickname for me. I said, “You are breaking all the dishes and we don’t have anything to eat on.” He said, “Okay, we’ll stop,” then he went downstairs. Ten minutes later, he continued breaking things. If you grow up in a house where people are violent, you may wind up having violent reactions.

Lucien would throw knives and plates at the wall.

I started a proofreading business company and went to work with my mother at John Wiley & Sons, a publisher, as a proofreader. She was doing secretarial work for an editor. Six months later, I started a company called Chystaline. My mother was a legal secretary at that point.

I trained proofreaders and sent them out. We didn’t have employees. We had independent contractors, and that is what put us out of business. The government declared that they were employees and I had to pay back taxes, which wiped us out. The IRS put a lock on our door.

DF: How did you meet your husband?

CD: I had come back to the city and was living at my godmother’s apartment, off her loft. I was depressed. My mother came over and said, “When I am depressed, I put on my make up and I put on a beautiful outfit and go to a coffee shop.” I walked into the little Italian café coffee shop across from Lafayette Street and met my husband, who was working with a friend at the café. He was living in an apartment over the café.

DF: Did you move upstate after your marriage?

CD: No. First, the state took all our available funds to pay the back taxes. I didn’t have any money to fight them. We didn’t have any money to live in New York City. I thought maybe it would be better to live in country if your poor. I had just had my son, and my mother had just died of lung cancer.

There were many shootings in the city and there had been a shooting at a subway station near my office that I would have arrived at, where a woman had been killed. A kid was also shot at the school my son was going to attend.

We decided to raise our son in upstate New York. It would be safer. I didn’t understand how upstate New York was a bastion of right-wing politics. If you are slightly different, you would be discriminated against. That was my son’s experience growing up in Oneanta and Guilderland. He and my daughter had an unhappy experience. Being poor is a big difference. Having frizzy hair is a big indicator, if you are an overt racist. Oh, there is something different about you?

My mother had died and I was very depressed. From that point on, I had clinical depression and never really got over it. I also had an anxiety disorder and probably have always had PTSD.

I thought this would be a better place. It certainly has more trees.

Lucien once asked me, when he walked into my room, which was the living room with a pullout couch. He asked me, “What do you think the meaning and purpose of life is?” I look at him. I was about 15. I knew what was happening was not normal and I had a distrust of him. I said, “Obviously to procreate. The purpose of all beings on the Earth is to perpetuate the species.” He looked at me and walked away.

Lucien was a person, and this goes back to the Beats, who was struggling all his life, trying to find the meaning of life, feeling alive and happy, and fighting off the futility of life. I know this because I once asked Lucien, why do you drink? “I don’t feel alive unless I am drinking,” he said.

I was a fiercely protective mother and my kids wound up moving thousands of miles from me. I was trying to protect them from all the bad things that could happen. I did what I thought I had to do. They thought I was an agent of the C.I.A.

DF: When you started digging into your mother’s history after she died in 1991, Lucien first tried to censor you, then cut you off.

CD: I find it hard to write, because I know I am betraying the secrets of Lucien and our family. These people could be sensationalized and simplified as horrible people. But they weren’t. I loved them. There were moments of happiness, but they were deeply flawed, traumatized and traumatizing.

You can’t really hate a person in a mental institution, for they are not right in the head.

DF: You waited until your 30’s to write about your mother Alene Lee. Was it difficult to dig into the material?

CD: In the beginning, at SUNY Oneanta, it was not depressing. I was an English major. I was a person who had a strong sense of the rights of children and was trying to regain women’s lost history.

My parents never took me to a museum. My mother took me to a library once. I had a very poor education. I really became educated when I went to college, through the humanities that I took. I had a fervor and a duty to uncover that history, and my advisor Professor Walker was very supportive. That was just the tip of the iceberg. I hadn’t gotten to the bulk of the boxes of my mother’s writing.

When we moved to Albany, I applied to graduate school at SUNY Albany in the English Department and was able to go through the Kerouac biographers’ transcripts. I wrote the 238-page thesis. I couldn’t find anyone to be my advisor. No one wanted to work with me on this project. The head of the department worked with me, but he didn’t like the Beats.

I was writing from the perspective of someone who should have been in the women’s studies or Africana studies. I wasn’t getting any positive feedback on the thesis. It kept on getting sent back to me with this or that correction. That thesis never got approved and then I got breast cancer.

I have always been influenced by people’s relative perceptions, a sense that they didn’t want me to do this. I just focused on being sick for however many years.

First, there was the breast cancer. Then I was going through a divorce. This was horrible. The children were losing their home, which had been willed to them by their grandparents When we divorced, my in-laws changed the will and left everything to their son. He took all the money he got from his parents, the life insurance policies. He disinherited our children, but gave them money to go to college.

I was devastated. I had always sworn because of my mother’s situation that I would never have kids without a husband, a father and a home. I had lost all three. I went into a deep clinical depression.

The doctors found a lump in my pancreas. They took out my pancreatic tail. I wound having a hysterectomy, and having my ovaries and cervix removed. They found lumps on my lungs. Over the last 10 or 15 years, they have been observing things. Six months ago, they found a new lump. Again, I have an ax hanging over my head. They are going to do a CAT scan, to see if the lump is growing.

In terms of the research, the more and more depressed I got, there was a deeper sense of futility. At this moment, I think, can I tell the things that happened? Will people think that my mother is bad? Will people think that Lucien was all bad? Will people think that I am bad? When you are poor, you wind up doing a lot of socially unacceptable things because you are poor and you do whatever you have to do to survive.

Writing is something a young person or a financially stable person can do. A person who is not financially stable cannot do it. You have to have a certain energy to write, in addition to whatever thing you are doing to support yourself.

DF: You have talked about a multigenerational trauma, that involves your grandmother, your aunts, your mother and yourself. There is also a fierce will to survive and a brutal resilience.

CD: My mother died of lung cancer and my father died of emphysema and COPD. For the last 10 years, he was on an oxygen tank.

The gift they gave me was COPD. I had undiagnosed COPD as a child. I was very athletic, but I could not run up stairs.

In the past 20 years, I got the diagnosis of COPD, though I have never smoked a cigarette in my life. I was the cigarette runner. They would send me around the corner to get a fifth of vodka and a carton of Kools. They both smoked five packs of cigarettes a day. The house was suffused with smoke. When the bars closed, they came home and smoked and drank.

I have been able to accomplish two things. My mother and I, her mother before her, and three of my four aunts, were involved in the African American project of surviving. We were not thriving. Only one sister, Aunt Russie, the numbers runner, thrived, economically speaking. The rest of us were on a mission to survive. My mother wrote, “I just can’t function in this world. I don’t seem to understand how to be here.” She did understand how to survive.

My project, my main goals was never to have children without a husband, to live longer than my mother and to tell her story. I haven’t finished telling my mother’s story yet, but I have been telling it in bits and pieces.

The thing I accomplished was what I told Lucien, I procreated. I love my children and I am glad I have them, but I do feel very hurt for them that I brought them into this world. We are in the 6th Great Mass Extinction.

My accomplishments are dubious, at best. I lived and I brought other people up here.

DF: Your children are self-sufficient. Your son has found his place in the world, as has your daughter.

CD: I called myself a Tiger mom, after the Asian women. Don’t mess with me, dude.

DF: Your mother has a very barebones entry on Wikipedia.org.

CD: Everything I had put in that entry on Wikipedia that had to do with Lucien or the Beats was removed. It’s as if [my mother] had no connection to the Beats at all. I don’t know how that happened. I don’t know who the editors were.

I am not concerned about it. My mother exists in books. It is more common now that people will mention her by name in books, and not use a pseudonym because she is not around to tell them to use a pseudonym. That was always Lucien’s idea.

What really nice thing that Lucien and Aline did, and they did it together to make my childhood a little better…the park across the street on Horatio Street was like “West Side Story.” There was a Spanish gang that lived by the river and an Irish-Italian mixed white people gang. They would fight over the park. I didn’t belong to any gang, so every time I went into the park, I would be assaulted. I was sexually assaulted by a member of the Spanish gang and was physically assaulted by one of the Italian gang members of the Irish gang.

The Irish gang all went to the Catholic church two blocks down. I didn’t belong to either gang, so I was shit out of luck. Lucien arranged a meeting with the Gallagher brothers, who were members of the Westies. They were leaders of the hit squad for the Mob. Lucien, two of the Gallagher brothers, my mother and I met the at the concrete park across the street. They apparently had a discussion on how I would be allowed to go to the park without being harassed. That’s the one nice thing my parents did, where they proactively interceded on my behalf.

This was one of the things that they did that I can look at fondly. Who meets with a hit squad from the Mob? They liked Lucien. He was an old newsman. They could relate to him.

In fact, for most of my childhood, they were completely unaware that anything had to be done, including breakfast, lunch and dinner, and buying clothing. My clothing came from second-hand stores. I was never knew where my clothes came from. I was never taken to a store to buy anything—sneakers, clothes, nothing, until I was a teenager, when I took myself shopping with whatever money I could get.

DF: How old were you when the events in the park went down?

CD: I was assaulted when I was eight or nine. We moved into Lucien’s house on Horatio Street when I was five and a half, for my first year at PS 41 down the street. I was so happy to go to school, because they gave me breakfast and lunch, and I would go to other people’s houses for things like peanut butter sandwiches.

I do want to say that when you said I had accomplishments and my kids were self-sufficient, I want to say yes.

My favorite song of the Beatles, and bear with me, for I am going to sing it, instead of saying it…I don’t know if I have all the words right, “Blackbird singing in the dead of night, lift your wings and learn to fly, all your life, you were only waiting for this moment to arrive. Blackbird fly.”

I do worry that the things that I’ve said about Lucien might hurt his sons.

DF: They are your stories.

CD: Nothing profoundly bad sexually happened with Lucien. He found another teenager to marry.

You know, the second time I saw Lucien cry was when Potsy died. Potsy was a black lab. Lucien loved that dog. When Potsy died, Lucien was weeping.

My dog is Evie. We walk in places up here where dogs can go off the leash, which is not many places. We are still the hunted.

Movement for me is physical therapy. We live a spartan life. We are technically poor, but I am always moving along, with my dog.

8 comments:

This interview is an important artifact that speaks to so much in American history, culture, and trauma. I am grateful for Diamente's work to uncover her mother's story and appalled that she could find no support in academia for the undertaking. I hope the time has finally come for this part of the story to be heard.

Thanks for your comments. It is unfortunate that a narrow-minded academic focused on the academic trends at the time did not see that value of Diamante's work in restoring the personal history of Alene Lee's life and struggles to the story of 1950's Greenwich Village and the Beats.

Hello.

Do you have an email for Christina? When I google her mother's name it says she was a writer but I cannot find information about her works. Does her daughter know what she wrote and where it is?

Thanks,

Hey Unknown--

There is very little of Alene Lee's writing on the internet, but I just found this website, Please Kill Me, https://pleasekillme.com/alene-lee/, where a few fragments of Alene Lee's writing were posted in March 2022.

Regards,

Dylan Foley

The Last Bohemians

Wow that is rather in-depth, thanks for sharing!

I've been searching for information about Alene Lee since I first heard about her as a Black woman fascinated with the Beats but never quite feeling like it was for me. Some of the Subterraneans mirrors experiences I've had-- I can't imagine how hurtful it would have been to be betrayed like that. I would be interested to read Christina's thesis if it's posted anywhere and I would definitely want to read Alene's work too.

Thanks for reading my article. You can find Christina Diamante's article about her mother on Beatdom.com. Beatdom also has Alene's essay "Sisters," about her teenhood on Staten Island.

What an interesting interview. I was looking to learn more about the women of the beat generation and those that inspired them. I was keen to hear their stories told by themselves and not just through the male perspective or interpretation. So thank you for this, knowing more of Arlene’s life from her daughter and her daughter’s story. Her story shows how a woman’s experience and opportunities were so limited and how the only voice allowed to be heard was that of a man’s. I won’t say it’s a sad story as the woman survived but it should be an important part of the critique of the beats and their work.

Post a Comment